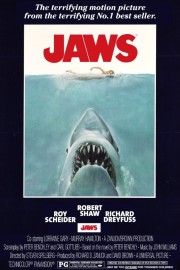

Jaws

Though they first collaborated on Steven Spielberg’s feature film debut, 1974’s “The Sugarland Express,” the legendary chemistry the director and his composer, John Williams, have been perfecting for the past 37 years was first hinted at in their second film together, “Jaws.” Williams had been around for over a decade before “Jaws,” but after “Jaws,” he became one of the masters of film music, building on this film’s success with memorable scores and themes for “Star Wars,” “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” “Superman: The Movie,” “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” and “E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial,” among many, many others. It’s no wonder– that two note motif that was the basis for his main theme are among the most famous in all of musical history.

For Spielberg, it was the first real glimpse of his cinematic genius after he spent several years directing television (most notably, “Night Gallery” and the pilot of “Columbo”), including the 1971 TV movie, “Duel,” which set the stage for “Jaws” after the character-driven “Sugarland Express.” That said, the genius Spielberg shows in “Jaws” was, in fact, plan B. In adapting Peter Benchley’s novel, Spielberg originally intended a more conventional approach to the shark attacks. Unfortunately, the mechanical shark bellied-up during the first test, leaving the director with a dilemma he solved by using a simple idea: implying the presence of the shark without, in fact, showing it. Williams’s theme is a large part of that approach, as well as the underwater cinematography by Bill Butler that shoots things from the shark’s point of view. In a lesser director’s hands, such touches would be heavy-handed (and for proof, check out this film’s three, progressively worse, sequels), but Spielberg had the subtlety at that point of his career to pull it off brilliantly.

In many ways, “Jaws” helped set the template for horror movies and blockbusters to come in its structure of this tale of man-vs.-nature, but watching it again, I think the real reason this works so well where so many after it failed is that it follows a simple story from beginning to end. The film doesn’t have any of the complications, narratively or morally, that other films would include. It’s just one damn thing after another from the moment Chrissy Watkins is taken in that opening night scene, which leads to Sheriff Brody (Roy Scheider) investigating the death, which leads to the great white shark terrorizing Amity Island during its busiest tourist time of the year. Brody is on his first summer as police chief, so he doesn’t understand, according to the councilmen and mayor (Murray Hamilton) on the Island, how his knee-jerk reaction of closing the beaches, shark or no, is ill-advised, and not as simple as he thinks. But when a couple of other people, including a young boy, are eaten, the mayor finally comes to his senses, giving Brody the authority to hire a fisherman named Quint (Robert Shaw) to go out and kill the shark.

That’s just the first hour of the film. “Jaws’s” second half takes us aboard Quint’s boat, the Orca, as he, Brody, and a scientist named Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) go fishing for the shark. It’s this segment of the film that sets the film apart from not only its sequels– which got patently more absurd –but also from so many other thrillers. While the adventure scenes where the trio face down the shark are exciting, fueled by skillful editing by Verna Fields and Williams’s tremendous music, it’s the character work as the three spend more and more time out in the ocean that distinguishes the film. The beating heart of this part of the film is after the first encounter with the shark, and the three are relaxing at night. Hooper and Quint begin to compare scars, which leads to a dramatic monologue by Quint (hauntingly read by Shaw, who helped write it) about the sinking of the U.S.S. Indianapolis during World War II, where 1100 sailors found themselves as potential shark food for three days after the battleship sank. Quint was one of those souls, and his words cast a dark shadow over the rest of the film for Hooper and Brody, who have read about sharks, but rarely dealt with them up close (although as we’ve learned earlier, Hooper has had enough experience to make them his life’s work). For Quint, though, we come to see this as a personal obsession (much like the captain in Moby Dick), and that inner rage informs not just his actions after the story is told, but helps us understand his behavior before the fact. How Shaw did not receive an Oscar nomination for the role is unbelievable when you watch the film, as is how Spielberg was left off of the shortlist for Best Director.

By all accounts, including Spielberg’s, “Jaws” was something of a miserable experience to film, especially since the director decided to actually film the scenes on the Orca in the ocean. And yet, the film remains a triumphant convergence of art and entertainment, the first of many Spielberg would be responsible for over the years. Part of that triumph is because Spielberg maintained his greatest focus on his characters rather than outrageous scenarios. It’s a theme of many his best films: ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances, whether it’s the trio of shark hunters in “Jaws”; the UFO-chaser in “Close Encounters”; the lonely boy who befriends an alien in “E.T.”; the eight soldiers on a mission to save one in “Saving Private Ryan.” This theme predates “Jaws,” though, as his protagonists in “Duel” and “Sugarland Express” faced equally extraordinary scenarios. With “Jaws,” however, Spielberg found a way to approach that theme in a way that was irresistible for audiences, and continues to be a benchmark in modern cinema to this day.