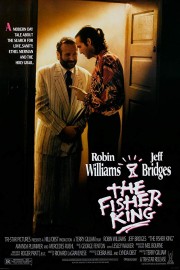

The Fisher King

The opening minutes of “The Fisher King” establishes the character of Jack Lucas perfectly: an early morning DJ, Jack is confident, narcissistic, and quite frankly, a dick. He’s a shock jock in the tradition of Howard Stern, putting one caller after another in their place, as he sees it, at least. He’s the hottest name in radio until a caller, who Jack had told that yuppies only cared about themselves, and weren’t as generous to people not of their kind, took his remarks too far, leading to tragedy. Three years later, Jack continues to be in a dark place because of what happened, and his life is a shell of what it once was.

The screenplay for this film was written by Richard LaGravenese, who doesn’t get enough credit for being one of the smartest, and most versatile, screenwriters in modern cinema. True, I haven’t loved all of his work (namely, “Beloved” and “The Bridges of Madison County”), but just looking at a list of his films (which includes, “The Ref”; “The Horse Whisperer”; “Living Out Loud”; and “P.S. I Love You,” as well as a couple of others I haven’t seen) shows an originality of voice, and powerful intelligence, that deserves mention with the finest writers of his generation.

Of course, LaGravenese isn’t the star of this film (his second as a screenwriter). That honor belongs to director Terry Gilliam, who, following the studio controversies of “Brazil,” and the ballooning budgets of “The Adventures of Baron Munchausen,” responded to the screenplay as an opportunity to do something small and personal. The Monty Python performer and animator may not have written it, but he understood the dark fantasy of LaGravenese’s story inside and out, while also grounding the film with painful, resonate emotions that roil just underneath his best films (namely, 1995’s “12 Monkeys” and 2009’s “The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus”).

Helping out with the emotional lifting are the stars of the film: Jeff Bridges (in one of his best, most vulnerable performances) as Lucas, and Robin Williams as Parry, a mentally troubled homeless person who believes himself a knight searching for the Holy Grail. Lucas and Parry meet through typically-outrageous, Gilliam-esque circumstances (Lucas was about to be set on fire by a couple of thugs, who were chased away by Parry), but more than just coincidence connects the two…Parry’s wife was killed in the tragedy Jack’s words to his listener inspired. Needless to say, that revelation shakes Jack to his core, and he decides that he needs to help Parry, even if it means following him on his fantastical adventures.

The more time that Jack spends with Parry, the more he begins to understand him, and the more he considers his own life. This is especially true when Jack sees Parry pining for Lydia (the lovely, mousy Amanda Plummer), which is responsible for the single, most profound moment of the film, when Parry is following Lydia in Grand Central Station, and the romantic longing leads to a scene of orgiastic dancing that I had forgotten about until Gilliam talked about it a couple of years ago at Dragon*Con. Watching it again, I was blown away by the sweeping emotion of the sequence, which is at once in tune with Gilliam’s work, but also feels apart from it, without taking one out of the film.

Watching Parry, hearing him discuss romantic notions of chivalry, inspires Jack to be a better person, especially to his girlfriend, Anne (played by Mercedes Ruehl in a bracing, Oscar-winning performance). And although Parry’s transformation is the focal point of the movie (and Williams is superb in not just the manic moments, but also the quieter ones), it’s Jack’s transformation, and Jack’s attempts at redemption, that are the beating heart of the film, and Bridges is a marvel of nuance and wicked charm. The thing that’s always been great about Bridges is that, his forte isn’t the type of hot-shot characters Tom Cruise plays, but rather people haunted by a past of sin and complication. True, his best-known character now is The Dude from “The Big Lebowski,” but his most memorable characters tend to fit the mold of a Jack Lucas, whether it’s: the weathered lawman of “True Grit”; the bomb expert of “Blown Away”; the extra-terrestrial hiding behind the visage of a dead man in the criminally-undervalued “Starman”; and of course, the alcoholic country singer he played to Oscar glory in “Crazy Heart.” There’s not a one of them that’s perfect and virtuous; they all have demons that need excised, and his Jack Lucas has more than a few that need to be fought. Of course, so does Parry, and for a time, it looks as though hope might be on both of their sides.

As always with Gilliam, however, the rug is pulled out from under our heroes. For the director, the idea of a Hollywood happy ending is bullshit sentimentality; for a truly heroic ending to occur, the main character has to hit rock-bottom, to have all hope removed from the equation. Only then will they be able to triumph. In this case, having actors as bold as Bridges and Williams in the main roles is essential to the film’s success. When I first saw the film several years ago, I saw all of this, but watching it anew, I found so many more profound ways in which it spoke to me. A newfound admiration for Gilliam as a filmmaker is a big part of my rejuvenated respect for his work, but my own emotional journeys, and those of some of my dearest friends, have put this film in particular in a new light for me.

It’s funny how great art works sometimes.