Paprika

The films of Satoshi Kon dealt, fundamentally, with the psychology of their characters, and sometimes, disjointed that psyche in ways that taught us more about the main characters than they even knew about themselves. Think about the pop music idol who goes mad in “Perfect Blue”; the actress remembering her early days in “Millennium Actress”; and the characters in “Paprika,” who have advanced psychological techniques so much that they have unparalleled access to their client’s dreams. The only exception in his cinematic work was his 2003 film, “Tokyo Godfathers,” which was a wonderful, heartwarming adaptation of a John Ford classic, and gave us intriguing insight into the director’s own psyche at its core. What strikes one most is how, in 2010 (the same year Kon died of pancreatic cancer), two Hollywood films found their own, unique ways to adapt Kon’s ideas: “Inception,” with its exploration of dreams that feels in tune with “Paprika,” and “Black Swan,” which told a story of obsession and the mental breakdown of a ballet ingenue that mirrors “Perfect Blue.” But Satoshi Kon always marched to the beat of his own drummer, and created a body of work that stands up with the very best of Japanese anime, and cinema in general.

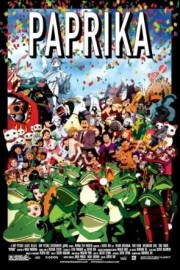

That doesn’t mean I’m any closer to understanding his final film, however. (And yes, I know he will be receiving directorial credit on the posthumously-completed film, “The Dream Machine,” but “Paprika” is the last feature he will be solely responsible for.) Watching “Paprika” for the first time in 2007 (or even the second time for this review), I feel like what audiences must have felt like when they first saw Disney’s “Fantasia”; yes, Disney’s film is ultimately more accessible, but as someone who has grown accustomed to being able to suss out the narrative core of even the most complicated animated films, “Paprika” is in a league of its own. Here’s a film that begins in the dream world of one character, moves on to a “real world” narrative about the stealing of a device that allows therapists enter their patient’s dreams as a way of healing them, and yet, merges the world of dreams with the reality in a way that, honestly, still has me confused beyond belief. Long-time readers will know my affection for Kon’s other films (especially “Perfect Blue” and “Millennium Actress”), but “Paprika” remains, spectacularly, over my head, although I still find it visually remarkable.

I use the word “spectacularly” because, despite my near-perfect confusion about the narrative and its reality (or lack thereof), Kon spends 90 minutes creating one of the most beautifully bizarre visual experiences I’ve ever seen in any movie. That alone is a reason for me to include “Paprika” in my collection, in the same way that I have “Perfect Blue,” “Millennium Actress,” and “Tokyo Godfathers.” Writing this review, however, I was reminded of another movie that uses the idea of dream logic, and the intertwining of reality and fantasy, to show audiences something they’ve never really seen before: “Total Recall.” Granted, even the 1990 original version by Paul Verhoeven couldn’t weave THIS convoluted of a tale, but as we see a detective (whose dream opened the film) navigating his way around the dream world, the similarities between the two were inescapable. Did that make it easier to comprehend Kon’s hallucinatory images? Not really, because in the tradition of the reputation anime has with non-watchers, the story is almost incomprehensible on any level of logic. Still, it gave me yet another signpost to consider whenever I watch the movie again, looking for answers.

One of the great things about anime (well, a lot of anime, at least) is how much it challenges the viewer to come to their own conclusions. Whether this is intentional or not, I’m not really sure; part of me thinks that a lot of the animators get so caught up in making the film as visually extraordinary as possible, they kind of forget logic when it comes to the storytelling. With his earlier features, Kon seemed in complete control of the narrative, so much so that he was able to twist conventional storytelling in ways that allowed for remarkable images and story to coexist. Unfortunately, it’s hard to find that type of control in “Paprika.” Still, when a film is this amazing too look at, it’s easy to get lost in what we’re looking at, and forget that we don’t really understand the story being told. It does make me all the more curious to see Kon’s “The Dream Machine,” when it eventually is made; will we see the masterful storytelling of “Perfect Blue,” or the self-indulgent visionary of “Paprika?” That’s for another review, one that will– hopefully –be able to be written sooner rather than later.