Capote

The minimalist pull of Mychael Danna’s score. The cold shots of the Kansas skyline and trees. Few films have been capable of exerting quite as haunting a mood as this biopic from first-time feature director Bennett Miller, until now best known for his acclaimed 1998 documentary “The Cruise” (unseen by me). Working from a profoundly rich script by actor/first-time screenwriter Dan Futterman (worthy of an Oscar for his efforts) based on the book by Gerald Clarke, Bennett has crafted a hypnotic drama about the years- from 1959 to 1965- spent by author Truman Capote researching and writing his classic masterwork “In Cold Blood,” his non-fictional novel chronicling the murder of the Clutters- a Kansas family- and the trial/execution of the two men convicted of the crime, Dick Hickcock and Perry Smith. The experience was exhausting emotionally and creatively for Capote- after “Blood” (made into a movie in 1967), he never finished another novel, and died of alcoholism in 1984. Those last facts we are told on title cards after the movie, and they only add to the impact of the film.

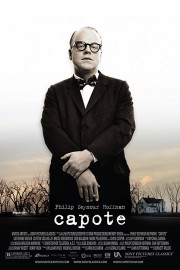

Muted in its’ tone, “Capote” is a work of brutal intelligence and honesty about the story its’ telling- not one of the three main characters comes off in a good light. Not Capote (played with icy feeling and cold intellectual brilliance by character actor Philip Seymour Hoffman, the deserving front-runner right now for Best Actor), who is as frankly honest about using the convicts- especially Perry- for the purposes of the story he wants to tell as he is about becoming close friends with them. When the latter occurs, Capote’s moral compass becomes twisted when he must await the results of their appeals for a stay of execution for the end of his book; their execution provides one ending, while their continual stay of execution brings the possibility that the story may never be resolved. His friend- “To Kill a Mockingbird” author Harper Lee (played with elegant intellectual wit and heart by the always terrific Catherine Keener)- puts this into perspective for Capote at the end with unshakable bluntness. And not the convicts Hickcock (Mark Pellegrino is pushed to the side as Capote and Smith’s relationship becomes the focus, but he makes an impression when he’s onscreen) or Smith- they do not pretend to be innocent of what they’ve done, and what they did do- we don’t find out the whole story of the murders until Smith finally tells it to Capote near the end- was done just as the title of Capote’s book implies- in cold blood.

Capote forms a unique and unsettling bond with Smith in particular, who he sees as a reflection of himself in a way- “it’s like they grew up in the same house,” as he tells Lee, though while Smith went out the backdoor, he went out the front. But how deep Capote’s feelings for Smith- played with mesmerizing dimensions by Clifton Collins Jr.- are something for further discussion. Openly gay (he has a relationship with a fellow writer played by Bruce Greenwood), Capote might also have developed a romantic fixation with Smith that the latter doesn’t seem totally unaware of himself. That both actors underplay any such connection that could have existed is a credit to their talents and their trust in their screenplay and director to not exploit such possibilities while not ruling them out either. The relationship is the centerpiece of “Capote,” and represents the haunted heart of the story’s dense and fascinating morality. I said earlier that few films have managed to exert such a haunting mood; fewer still are the ones that don’t back down from it from the first frame to the last. “Capote” stays with you for that very reason.