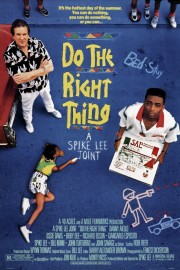

Do the Right Thing

Spike Lee’s focus as a storyteller has never been stronger than it was in his provocative masterpiece, “Do the Right Thing.” The film created a storm when it debuted at the Cannes Film Festival, and again when it opened in theatres later that summer, and it’s easy to see why. It’s the boldest film about race relations since the flawed landmark, “The Birth of a Nation,” and it shows that in the 74 years between the films, things are as troubling as ever. Twenty-four years later, despite the re-election of our first African-American president, we still have a ways to go.

Like his teacher at New York University, Martin Scorsese, Lee has expanded his filmmaking output by going between narrative features and documentaries, and that’s only proven his greatness. His features are very hit-and-miss, but his docs are uniformly excellent, and they put his social consciousness into focus. He’s not afraid to court controversy, and he sometimes stirs things up needlessly publicly, but his importance as a filmmaker is evident in every film he makes, even if that film is lousy.

in “Do the Right Thing,” Lee stars as Mookie, who works at Sal’s Famous Pizzaria on a block in Brooklyn. His boss, Sal (Danny Aiello), likes him, as does one of Sal’s sons (Vito, played by Richard Edson), but he also has run-ins with the other son, Pino (played by John Turturro). It’s a hot day on the block, both literally (hitting the century mark), and figuratively– tensions are running high, and primed to explode when a young man named Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn) is killed by a cop. Of course, he’s been blasting his boom box, which has bothered everyone from Sal to the three older black men on a corner.

By setting his story on a single, diverse block in Brooklyn (with whites, blacks, Italians, Koreans, and Latinos populating it), Lee both creates something small enough to be taken in fully, but broad enough to state universal truths that anyone can relate to. Well, if they allow themselves to relate to it. Too often, Lee’s films tend to be subjugated to the status of just being “black movies,” although he has found commercial success with films like “Malcolm X” and “Inside Man,” and did find a crossover audience with this film and “She’s Gotta Have It.” But while most of his films, both narrative and documentary, speak more greatly about the African-American experience, the intelligence and insight of his best films speaks to struggles that anybody can relate to. Maybe not the specific events, of course, because let’s face, a white man from Ohio (and Georgia) can’t even begin to comprehend what it must have been like for someone like Lee in his life, but the emotions that come through in his films, from this film to “4 Little Girls” to “25th Hour” to “When the Levee Breaks,” are indelibly powerful. Never is that more true than when all of the tensions that have been building up all day culminate in a riot that starts over little things, but becomes a flashpoint for just how much further we still have to go before we can be “a more perfect union.”

The ending of this film is truly painful, because no one does the right thing. Not Mookie, who throws the trash can in the window at Sal’s that leads to its destruction. Not Sal, who didn’t need to destroy Radio Raheem’s boom box when provoked. Not Radio Raheem, who could have chosen love, and turned his boom box down anyway, but instead chose hate when his beloved radio was destroyed. Not Buggin’ Out (Giancarlo Esposito), who leads a boycott against Sal’s because he only has Italians on his “Wall of Fame,” even though it’s the blacks in the neighborhood who pay his bills. The elders of the block (Da Mayor, played by the great Ossie Davis, and Mother Sister, played by Ruby Dee) are powerless to stop things, and even incite ugliness before standing up against it. But who am I to condemn any of these character’s actions? That ambiguity, and uncertainty, of what’s “right” and “wrong” in the face of tragedy is what makes Lee’s film (which is disarmingly entertaining as well) so unflinching, and unforgettable.