The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

Watching his films over the past few years, I’ve noticed a certain similarity between John Huston’s films with those of the great Japanese master, Akira Kurosawa. The fact that Kurosawa was heavily influenced by American cinema is part of the comparison, but more than that, both directors made films about fundamental human truths that moved past the genre the movies were made in.

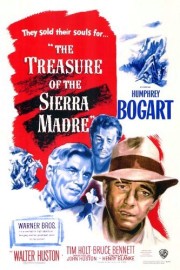

Take “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre,” Huston’s great 1948 film, for which he won Oscars for Best Director and Best Screenplay, as well as directed his father, Walter, to a Best Supporting Actor Oscar. On the surface, the film is an adventure piece, although even at the start, when we see Humphrey Bogart’s Fred C. Dobbs as he begs people for money on the streets of a Mexican town, we can tell that Huston is aiming for bigger moral goals. By the time Dobbs, a fellow American, Bob Curtin (Tim Holt), and old-timer Howard (Huston) set off for a little-mined reservoir of gold, we’ve already seen how greed plays an important part of the story; Dobbs has hit up the same businessmen three times for change and a meal, and a man who hires he and Bob for an oil job stiffs them on payment. What will happen when Dobbs, Bob, and Howard find gold for themselves?

Of course, the movie is 65 years old, so a lot of people can answer that question for themselves. Or can they? Yes, the film is an Oscar-winner, and justly famous, but is it as well known as Huston’s first film with Bogart, “The Maltese Falcon?” Possibly, but since the most famous quote from the film– “Badges? We don’t need no stinkin’ badges!” –is actually a misquote, it’s unlikely. However, the film is superior to “Falcon,” not just because of its Oscar success, but because of how elemental it is about the human condition. Based on the novel by B. Traven (a pseudonym; the author’s real identity is unknown), “Madre” sets the stage for danger, and death, early on. No doubt the result of having been shorted his hard-earned money by the oil man, Dobbs is the most susceptible to paranoia after the three strike gold, and become very, very wealthy. This is a far cry from the smooth, romantic Bogart from “Falcon,” “Casablanca,” and “The Big Sleep,” and the actor (never better, even in his later, Oscar-winning role in Huston’s “The African Queen”) knew it. Roger Ebert, in his Great Movie review of the film, recalls what Bogart said to a critic one night in New York about the role: “Wait till you see me in my next picture. I play the worst shit you ever saw.” I don’t know if I’d say that, Dobbs feels more like a good person beaten down by life than a real bad guy, but seeing him delve into madness is at once tragic and darkly funny, a balance Bogart and Huston get just right.

It isn’t just the writing and acting that makes “Madre” feel so sharp and vital all this time later, however. Rather than film the movie on sets and in locations in the States, Warner Bros. sent Huston and co. on location in Mexico, which not only lends an authenticity to the images and the story, but also gave the filmmakers freedom to hire locals for extras and supporting roles. That makes the movie feel less like a Hollywood western, which it is at its core, and more like the Italian westerns that would spring up in the ’60s. It doesn’t feel THAT much like the Italian westerns– it’s still, very much a Hollywood production –but there is something uniquely original about the way Huston films this story that makes it stand out among other movies not only in his own cinematic legacy, but in Hollywood history as well.

What happened to the time when filmmakers worked within the confines of genre, and created bold, adventurous masterpieces of storytelling and character exploration, the likes of which Huston did here? Back in the golden age of the studio system, filmmakers like Huston, John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock, and many others didn’t see genres like the western or the adventure as simply an opportunity to make entertaining films; at their best, they found ways to delve into personal storytelling that challenged audience perceptions about what cinema could do, and more specifically, what certain genres were capable of. Now, there’s a much wider disparity between the films that win Oscars and the movies that make up the bulk of Hollywood moneymakers year in and year out. However, what “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” proves is that the two are always capable of being one in the same, so long as the filmmaker at the center of the action has the courage, and purpose, of someone like John Huston, who made films for the audience, as well as himself.

Here are some more thoughts on the film, written for a class on “Language of Film & TV” I took during the summer of 2014:

There were a lot of rich choices on the AFI’s 100 Greatest American Films list from 1998 to choose from for analysis. After much consideration, I chose one of my favorites from the era- John Huston’s “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.” A big part of the reason I chose “Madre,” apart from it’s unabashed greatness, is how much it has in common with different types of genres, yet doesn’t really seem to fit into one in particular.

The genre I would identify “Madre” with the most is the Western. The setting, the costumes, and the central story about searching for gold, are the biggest indicators of this iconic American genre’s influence on the film, but this isn’t a story about cowboys vs. indians. This is a story about two young men who find themselves in Mexico, out of work and out of money. One is making something of a living shining shoes, but the other (Bogart’s Fred C. Dobbs) is a panhandler, trying to scrape together some money to stay alive. After they get swindled by a businessman, they run into an old prospector who tells them stories of gold in the mountains. After they the get money together, they are off on the adventure to find gold. This is not the traditional western story, but it plays off of common themes for the genre such as greed, betrayal, and honor among men, even if they’re on opposite sides of the law. There are desperadoes in the form of Mexican bandits who pose a threat to our main characters, and there’s a wise old man in Walter Huston’s prospector, who has seen first hand what gold does to men’s hearts. However, while “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” fits in within the archetypes of the Western genre, I’m not sure whether I would consider it a Western in the same way “The Searchers” or “Unforgiven” or “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” are.

Another genre to consider is that of the adventure film. This is a film about characters leaving the life they’ve lead in search of bigger things, for better things, and finding excitement along the way. That’s the essence of an adventure, whether you’re talking about “Star Wars” or “The Adventures of Robin Hood” or “King Kong,” and “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” fits that bill. What distinguishes it from the films we associate with the adventure genre, however, is a lack of real action and set pieces; this is an external adventure the characters go on (with the characters braving desolate lands, and dangerous thieves for a chance at personal glory), to be sure, but the drama of the film is more internal. Rather than simple heroes and villains, the main characters in “Madre” are more complicated, with personalities and characteristics that don’t fit into traditional story roles, and a “hero” in Fred C. Dobbs that is anything but heroic by the end of the film. Dobbs becomes paranoid about maintaining what is his, and even speaks of taking the gold his companions find for his own. This is not the mark of what we’ve come to expect from our adventure movie heroes, and is certainly a far cry from the romantic hero Bogart played in “Casablanca,” who put the larger picture ahead of his own personal goals. This is a selfish individual who cares more about himself than he does others. In that way, and many others, “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre,” while having several of the characteristics of an adventure film, is nonetheless outside the mold of the genre.

I pose the question in my subject heading about “Sierra Madre,” “A movie without a genre?” That’s a bit too broad an assessment, especially from a movie made within the Hollywood system, with two of the most important names in filmmaking history attached in John Huston and Humphrey Bogart. At it’s core, the film fits very much into the realm of a dramatic film. However, if one were to try and place the film in a more specific genre of filmmaking, I’m afraid such an analysis might prove to be a bit tricky, because like any other great piece of cinema, the film doesn’t fit snugly into one particular form of storytelling.