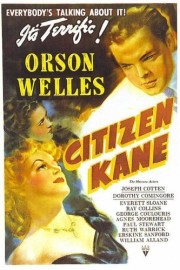

Citizen Kane

The idea of writing about “Citizen Kane” is a daunting one. Is there any new ground to possibly write about in discussing Orson Welles’s first film, which, for many years, was the “official” best film ever made? (It was supplanted in 2012’s Sight & Sound poll by Alfred Hitchcock’s “Vertigo.”) I don’t know, but since I have reviewed many other Welles films, I would say it’s about time to review what many consider his definitive film, wouldn’t you?

The film starts in mystery, as the camera moves closer and closer into Charles Foster Kane’s palace in Florida, Xanadu. We see Kane in his bedroom. He is holding a snowglobe of an idyllic winter scene– a snow-bound house, and a sled in the front yard. He utters a single word, “Rosebud,” before dropping the globe, and dying. The remainder of the film, from the moment a “News On the March” reel on Kane’s life ends, to the final image of a sled burning, is about the mystery of that word, and a reporter, Mr. Thompson (William Alland), who seeks out associates of Mr. Kane to find out the truth about that word. Of course, that truth has been well known by movie fans for decades, but it doesn’t stop “Citizen Kane” from being an intriguing cinematic experience.

Part of what keeps the film alive after 72 years, and one of the benchmarks of cinema in general, is the film’s bold experimentation. This part of the film’s legacy is well documented by those more knowledgeable than I am. It’s hard to see how experimental the film is these days, and that’s part of why I’ve always had a hard time warming up to the film the same way others have, and the same way that I have other Welles films, from “Touch of Evil” to “The Trial” to “F for Fake.” But as with any great film, one can easily see how the cinematography by Gregg Toland (whose use of deep focus and high angles is the most famous technical contribution to the film); the editing by Robert Wise (who became a great director in his own right, most notably with “The Day the Earth Stood Still”); and the score by Bernard Herrmann (who was a Welles collaborator on the Mercury Radio show, and became a great film composer working with Hitchcock) add to the film’s overall effect.

It’s the performances, however, that ensure the film’s long-lasting impact on viewers. Arguably the finest one is Joseph Cotton as Jed Leland, Kane’s best friend, and harshest critic. He is with Kane from the beginning, and even after their falling out following Kane’s failed gubernatorial run, and the debut of Kane’s second wife in a Chicago opera house, where her performance is dismal, he still cares enough about his friend to be honest about him to Mr. Thompson. Another great performance is by Everett Sloane as Mr. Bernstein, Kane’s financial adviser, and the one person who stood by Charles through thick and thin. He was, in essence, a “yes man,” but he’s a sympathetic one: foolhardy in his support of Kane, but poignant in a scene with Thompson in which he recalls a girl he saw at a train station. They never met, but he thought about her every day of his life afterwards. That story is, in a sense, a mirror into Rosebud on the part of Welles and co-writer Herman J. Mankiewicz, who won the film’s only Oscar for their screenplay. Throughout the entire film, Welles and Mankiewicz put hints and clues into the nature of Rosebud, and leave it to us to see if we can figure it out for ourselves.

In the end, though, Welles is the star of the film, both in front of, and behind, the camera. He gave better performances later, especially as the sad, corrupt cop in “Touch of Evil,” but his Kane is exactly what the character calls for: cocksure, arrogant, energetic, full of youthful defiance which he would maintain, even after old age, and political ambition, turned him into a stone-hearted shell of the man who wrote, and published, a “Declaration of Principles” in his newspaper when he still cared about people other than himself. Twenty-five when he made “Citizen Kane,” Welles the man never lost his youthful fire, and the principles that made this film, and every one he directed afterwards, regardless of production difficulties, a profound, even transforming, work of art.