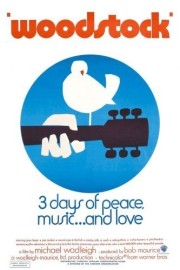

Woodstock

I was born 8 years after the Woodstock festival in 1969, but it seems as though it’s been a part of my musical passion my entire life. It’s closer to 20 years, really, when I found the soundtrack album from the festival in my parent’s collection of albums as I was developing my own musical tastes, and it did a number on me. It was a regular part of my listening habits for a while, and one of its premiere stars, Jimi Hendrix, became a favorite of mine, especially with his iconic, blistering performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner” in the early hours of Monday. However, it would take several more years before I saw the Oscar-winning documentary of the film, which became a monument for the ’60s, and the Baby Boomers generation.

Calling “Woodstock” a documentary is more appropriate than calling it a concert film, despite the plentiful musical performances it features. Director Michael Wadleigh’s film is about the festival, in every one of its aspects. We see the preparation of the fields in upstate New York; the building of the stage; the arrival of the concertgoers, whose numbers so overwhelmed the people putting on the show that they were forced to make it a free concert; and the perspectives of the townspeople, who were, needless to say, overwhelmed as well, but also happy to host these people. I wonder if any of them, including Wadleigh and his crew (which included Martin Scorsese and his editor, Thelma Schoonmaker), knew they were in the middle of something historic? Some might have had delusions of such grandeur, but I’d be curious to have seen their faces when, barely a year later (when this film came out in 1970), and then in the years to come, they were proven right.

Watching the film, it’s hard to figure out which are the most memorable parts– the musical performances, or the scenes that capture the energy, and perspectives, of the people who were watching the festival. Yes, the festival had a great many icons and famous performances, but who watches this film doesn’t remember the announcement made warning people about the brown acid? Or the couple who had been living together for five months before the show, and came to see what was happening, and be in the middle of it? Or the scenes when it begins raining? Or the scenes of people walking over the fence when it becomes a free concert? Or the classic moment when two people, naked, go into the bushes and make love? And who can forget the Port-O-San man, who had to be something of a hero for how he made it possible for more than 400,000 people to relieve themselves amid the chaos? Wadleigh and his collaborators used 16 cameras, and shot 120 miles of film, and by utilizing split screen to give us the full picture of that weekend for 224 mesmerizing, entertaining minutes (for the Director’s Cut), it feels as though they used every last frame of it. And yet, there isn’t a dull moment to be had.

Nearly four hours of film is tough for even some of the greatest films to maintain, and that’s where the musical performances play a huge part in the film’s success. Music is the most subjective of art forms, so naturally, not every act and song is going to land, but Wadleigh comes really damn close to capturing a perfect concert on-screen through his selections. Yes, he had a lot of material to choose from, but as much as he got it right, he could have easily gotten it wrong. The music has a very clear through-line in energy and importance when it comes to following the themes of love and peace that the festival was meant to convey, and which comes through with everything from Joan Baez’s soulful performances of “Joe Hill” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” to Ten Year’s After’s “I’m Going Home” and Sly & the Family Stone’s “I Want to Take You Higher.” There’s plenty more musical goodness than that, however: it’s hard to speak out against the longing in Joe Cocker & the Grease Band’s “With a Little Help from My Friends”; Arlo Guthrie’s “Coming Into Los Angeles”; the rebellious spirit of Richie Havens’s “Freedom”; the folksy, anti-war “I-Feel-like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag” from Country Joe McDonald; Santana’s “Soul Sacrifice,” which is enhanced through the filmmaker’s bold editing and brilliant syncing with the furious rhythms; and, of course, the Hendrix trio that ends the film, and shows people leaving the grounds, leaving trash, and personal belongings, behind in the muddy mess that resulted from the rain of the weekend, and the thousands of bodies that converged for something special.

I’m not sure whether I’d call “Woodstock” the greatest documentary of all-time, but if it isn’t, it’s sure as Hell close to the top of that list. What Wadleigh and co. made is what a great documentary should be: a document that brings us up close and personal with its subject matter, and gives us a glimpse of life we may not have gotten otherwise; of people who are fascinating in their complexities and meanings; and of events, big and small, that nonetheless have great importance for the subjects, and possibly, teach us a little bit about ourselves, and give us something to wrap our brains around. When I found that album of Woodstock in my youth, and listened to it, I just looked at it as a collection of great music, of music that would inform my own tastes over the years. By the time I first saw the film, “Woodstock,” though, and watching it again for this review, I have a greater understanding of what a seismic cultural event Woodstock was, and more of what it represented not only to the young people who ventured up to that farm in New York in 1969, but also to people like myself, from the post-Woodstock generations, who have captured the rebellious spirit of the festival for their own, and tried to incorporate it into our own lives. It’s not always easy, but as society feels more oppressive to the rebels who want to challenge the system, that spirit is sometimes the only thing that keep us going, regardless of how we channel it.