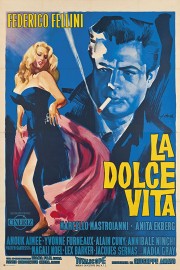

La Dolce Vita

Before many of us had even heard of the term “paparazzi,” let alone the practice of journalists following celebrities and well-known people for stories, Federico Fellini introduced the world to them in his 1960 film, “La Dolce Vita.” The title means “the sweet life,” but there’s much pain and sadness in Fellini’s immortal tale, and that is intentional, I think. Fellini’s point, which is still vital today, it that “the sweet life” isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, and to pursue it with reckless regard leads to an unfulfilled life, spiritually. The characters in the film may seem shallow and materialistic, but Fellini gives us access into private moments that show us who these people really are, and it’s not always a pretty sight.

Did the term “paparazzi” ever have a positive connotation? It’s hard to imagine while watching “La Dolce Vita,” and even harder to imagine given how ruthless and (unfortunately) prevalent tabloid journalism is in our modern society. Today, media trainwrecks such as Lindsey Lohan and (recently) Justin Bieber dominate the news, and wealthy, vapid individuals like Paris Hilton and Kim Kardashian are celebrities for doing…nothing, in particular. What’s resulted is a fascination in celebrity races to the bottom that are worth a lot to the “reporters,” if one can even call them that, and a news media interested more in scandal and speculation that actual journalism. I would also argue that it’s given rise to the “reality TV” that has given us plenty more to gossip and obsess over, as well as given critics plenty of reason to see the world as being in a descent into decadence and immorality. In that way, “La Dolce Vita” is particularly prescient, and served as a warning of what might happen if we didn’t change course. Why didn’t we listen?

Probably because for all its sadness, Fellini’s film is also one of the most joyous experiences in all of world cinema. It was the dividing point between his neorealist films such as “La Strada” and “Nights of Cabiria” and what we consider “Fellini-esque,” which was best exemplified in his next film, “8 1/2.” Had Fellini told a story of tragedy that was easier to pin down, maybe society would have become less interested in the exploits of the wealthy, and we would live in a very different world. But Fellini (aided, as always, by the great Nino Rota’s score) was incapable of such turgid morality tales, and couldn’t help but make his film fun; that’s, ultimately, what made Fellini “Fellini,” and was a driving force in all of his films.

Back to “La Dolce Vita.” The film, for those who do not know, follows the nights and days of Marcello, a journalist who is part of the paparazzi, but who has hopes of being a serious writer. He is caught up in “the sweet life,” and is well known and respected, but in his eyes (the memorable eyes of Marcello Mastroianni, who also starred in Fellini’s “8 1/2”), we see sadness, and a longing for purpose in his life. He has a fiancee, but he’s hardly home, and she has become suicidal. He also has a dear friend in Steiner (Alain Cuny), an intellectual who appears to have everything he wants, but, as Marcello will learn, is missing an important piece…happiness, something Marcello is trying to chase down as well, but to no avail.

The film is presented not as a straight-forward narrative, but rather, a series of vignettes and moments that follow Marcello through his life. The film opens with a Jesus statue being helicoptered in to Rome and the Pope– Marcello is in one of the helicopters, and, when he sees a group of bathing beauties, tries to get their phone numbers, but is misunderstood. It ends with a similar scene of Marcello and his friends finding a sea monster on the beach, trapped in nets. He sees the image of a young girl who, earlier in the film, he met while trying to write his novel, but once again, the communication is garbled. Roger Ebert illustrated the great parallels of these scenes in his review of the film better than I could, but it’s easy to see that parallel, and how Fellini plays with our notions of dichotomy between the sacred and profane throughout the film. In the middle of the film, there’s a night sequence where the paparazzi and believers converge on a field where two children claim to have seen the Virgin Mary. The scene becomes a circus, as the children lead the adults on a chase, claiming they see here here, and then there, and then somewhere else. After a while, the crowd disperses, having caught on to the rouse, but we see that someone has died, likely caused by the frenzy. Again, the notion of the sacred and profane is subverted by Fellini, with the circus that inspired the faithful seen in a negative light, while the “real” moments in life, like the dead sea monster, and the woman who, after a false chase, finds peace, are treated solemnly, with a dignity that brings us closer to the spiritual.

It would be easy to go through each scene and illustrate the greatness Fellini puts on display in each one, but I’ll leave that to more learned minds like Ebert, who does so quite elegantly in his Great Movies review, which also shows how personal the film was to him. With that in mind, there’s a quote that struck me deeply watching the movie for this review. It comes from Steiner, who says it to Marcello during a dinner party at his home. Marcello is confiding in his host about how he finds solace at Steiner’s home, and in his life, and wants that type of happiness for himself, unaware of the despair Steiner feels. Steiner tells Marcello, “Don’t be like me. Salvation doesn’t lie within four walls. I’m too serious to be an amateur, but not enough to be a professional. Even the most miserable life is better than a sheltered existence in an organized society where everything is calculated and perfected.” It’s the part in the middle that spoke the most to me, but the truth is, the entire quote is completely accurate, and speaks as much about modern society as it does to the life of 1960’s Italy. Both Steiner and Marcello find themselves trapped by society, but in different ways. For Steiner, there’s only one way out, and it’s the most horrible way imaginable, and it leads to the cruelest moment in the movie when the paparazzi move in on his wife in the aftermath. For Marcello, there’s still hope for him to break free, but it’s a faint hope, made fainter by Steiner’s demise, after which Marcello engages in an evening of debauchery with his “friends.” He is made numb, with nothing able to make him feel something. “The sweet life” isn’t so sweet anymore. It’s a bitter pill, and Fellini knew it then. Unfortunately, as a society, we believe otherwise. Like Marcello, we find ourselves alternately disgusted and fascinated by this life, making it difficult to dig ourselves out of it. Marcello wasn’t able to do so. Will we have better luck?