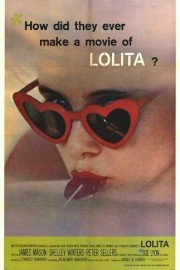

Lolita (’62)

It’s been about 15 years since I first became familiar with the story of Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov’s tragic tale of a British intellectual who falls in love with a Middle American teenage girl. I can’t remember whether it was Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 adaptation or Adrian Lyne’s 1997 version, which was released briefly in theatres in 1998, that I watched first, but I know which one made the strongest impression. I was relatively new to Kubrick’s cinematic worldview, and Lyne’s was just more accessible, and befitting the story. It was a remarkably emotional experience, while Kubrick’s film seemed more uneven, though no less intriguing. Now, having seen most of Kubrick’s films, it’s time to return to the world of “Lolita,” and see whether it has a bigger impact the second time around.

But of course it would– every Kubrick does, even if it did the first time. Working from a screenplay by Nabokov himself, Kubrick’s vision of the film is more observational than Lyne’s was. Lyne, who had previously directed “Fatal Attraction,” “9 1/2 Weeks,” and “Indecent Proposal,” throws us right into the psychological turmoil of Humbert Humbert, whose infatuation with his landlady’s young daughter destroys him emotionally, and morally. Kubrick is more analytical: rather than judge Humbert (played beautifully in this version by James Mason) for his transgressions, he simply shows them to us, allowing them to unfold gradually, all the while having teased us with the tragic path Humbert’s obsession leads him to.

The film begins as Humbert, who has lost Lolita (played by Sue Lyon), drives to see the writer, Claire Quilty (Peter Sellers), who had taken her away. Quilty is a fellow lover of young girls (indeed, a pedophile), and Humbert is on his way to kill him. However, Humbert’s motivations are less because of a sense of right and wrong, but rather, because Quilty ruined Humbert’s happy life, where he and Lolita could live in relative peace. Humbert confronts him, but Quilty, who is hungover, and battling his own demons, acts as though he doesn’t remember. In a rage, Humbert shoots him, and Kubrick takes us back four years, when Humbert was looking for a boarding house before he begins a teaching position in a New England university. He comes across the house of Charlotte Haze (Shelly Winters) and her daughter, Dolores (who goes by Lolita), and from the moment he sees the young Lolita, he’s found his home. The three form an uneasy family, but while Charlotte falls in love hard for Humbert, Humbert only has eyes for Lolita, and just his luck, she seems to have her eyes on him, as well. He goes into a depression, however, when Charlotte sends Lolita off to a summer camp, and when Charlotte offers marriage, he sees it as a chance to keep close to Lolita, although his duties as a husband keep him depressed. One day, Charlotte finds the diary in which he’s written about his affection for Lolita, and his disdain for Charlotte. It drives her over the edge emotionally, and before Humbert can calm her down, she runs out of the house, and is hit by a car, dying instantly. Now, it is just Humbert and Lolita, and he takes her out of the summer camp, and claiming that Lolita’s mother is only “ill,” he takes her on a cross country road trip, which makes up the bulk of the film.

I think what really took me aback the first time I watched Kubrick’s “Lolita” is the way he presents Quilty. The more I watch, the more I’m certain I saw Lyne’s film first, because the characterization of Quilty, I believe, in Kubrick is such a disarming experience, especially compared to Frank Langella’s sad portrayal in the Lyne film. This was the first of two back-to-back collaborations between Kubrick and Sellers, and it’s striking how much latitude the exacting Kubrick gave the actor in both this film and “Dr. Strangelove” to change the tone of the films almost single-handedly. Of course, in “Strangelove,” the point was satirical comedy from beginning to end, but “Lolita” is something very different. “Lolita” is a drama and tragedy first, but when Quilty is on screen, he brings an almost absurdist humor to the proceedings that turn it into a bizarre comedy that feels out of sync with the rest of the movie. It’s an interesting experiment, but one that almost sinks the film into an abyss of unfortunate choices. But Sellers and Kubrick are too gifted for that, and even if their creative decisions fall flat at times here, it’s all too easy to see that these two made for a unique pair of collaborators.

Sellers’s performance in the film is so memorable, for better or for worse, that it almost runs the risk of overshadowing the other actors in the film. As Humbert, Mason is a marvel of moving between happiness and pain; humor and heartbreak; comforting and dangerous. While Jeremy Irons is pure pain, tragic hero in the later film, Mason is a bit more ambiguous; the backstory that cements his obsession with someone like Lolita is less spelled out, making his downfall more devastating to watch. As Lolita, Lyon is assertive and matches Mason beat-for-beat with a flirtatious, seductive allure befitting the character. She’s a little too assertive, though; it feels like the character should be more innocent if the tragic nature of the story is to have an impact, though given the controversial nature of the story, it’s understandable why Kubrick would go this way. And as Charlotte, Winters makes a vivid impression with her chipper, unrequited love of Humbert, who doesn’t deserve a woman so good in his life. Kubrick doesn’t judge him, however; he is merely an observer of Humbert’s life, and the unfortunate choices he makes that spell doom for everyone in the film.

Kubrick said later that, had he known the type of interference he was going to run into with the censors, he might not have made that film. Regardless of how conflicted I am about the final film, however, I’m glad he did, because it was the first in a run of iconoclastic films during which Kubrick established himself as the icy, perfectionist master he is regarded as today. Without “Lolita,” would we have gotten “Dr. Strangelove?” Or “2001?” Or “A Clockwork Orange?” Or “Eyes Wide Shut?” Possibly, but it’s just as likely as we could have gotten a very different filmmaker, and Kubrick would have had a very different legacy. Without that time with “Lolita,” though, he might not have continued challenging audiences, and the Hollywood system, with movies as provocative, and fascinating, as this one.