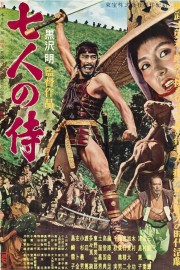

Seven Samurai

Bandits rule the rural lands in 17th Century Japan. Every farming season, they come to villages and take what plunder and food they can, promising to return when the village has more. One village cannot live like this anymore, as they are starving, with no food left for themselves. The elders have an idea: hire samurai, roaming warriors, to fight the bandits for them. What can they offer, though, with little money, and barely any food?

This is the basic premise of Akira Kurosawa’s great epic, “Seven Samurai,” a film that is, arguably, the most influential action movie of all time. Yes, it inspired movies directly, like the western remake, “The Magnificent Seven,” and even Pixar’s “A Bug’s Life” (which turned the story into a comedy of mistaken identity), but more than that, it set the template for how later event movies, ranging from “Star Wars” and “Independence Day” to “The Avengers” and “Avatar,” told their stories. Search your memories of these movies, and watch “Samurai” for yourself, and you’ll see what I mean.

Kurosawa made many samurai movies in his life, but no two were alike, even when they followed the same character in “Yojimbo” and “Sanjuro.” Neither of those films are similar to “Samurai,” or “The Hidden Fortress,” or “Kagemusha” or “Ran” in the type of story they tell, but the moral code, inspired not just in ancient Eastern philosophies but also the emerging traditions of the West, was the same from film to film. Like the greatest filmmakers, Kurosawa, often at least a co-writer on his scripts, found different ways to tweak this code in each movie, so as to assure that we never saw the same movie twice.

“Seven Samurai” is his longest such movie, at nearly 3 1/2 hours, and Kurosawa doesn’t waste a moment. Much of the first part of the movie is spent with a handful of villagers as they search for the samurai that will help them. Once found, they don’t return to the village immediately, giving us a chance to get to know the seven, the leader of whom is the oldest, Kambei (Takahi Shimura, the star of Kurosawa’s previous film, “Ikiru”). He’s been around for a long time, and understands the hardships of live as a samurai, but also feels the plight of the farmers whom have hired him and the other samurai. The only other samurai who also has that insight is Kikuchiyo, played by Toshiro Mifune, Kurosawa’s other favorite actor to work with besides Shimura. Kikuchiyo is high-spirited, eager to fight the bandits, and is hugely charismatic with the people in the village, especially the children. He’s also not one who has spent his life as a samurai; he wasn’t born into the traditions the way Kambei or the other samurai were. He actually comes from a farmer’s tradition, but the fact that he is neither one nor the other completely sets him apart from both the villagers and the samurai. The intensity with which he behaves, however, will be beneficial to both once the attacks from the bandits begin, though.

When that starts in the second half of the film, and sustains through to the end, this is where Kurosawa shows his mastery of the art form. Even though filmmakers like Spielberg, Coppola, and Lucas revered the director (Hell, “Star Wars” is like one, sloppy kiss to Kurosawa from Lucas), none of them can match “K” when it comes to action. The Japanese master remains in a class by himself in that respect, as he maps out the geography; lets us in on the strategies he employs; and follows action on multiple planes, in multiple areas, all at once. You get the sense that Kambei is the on-screen avatar for Kurosawa from the time he and the villagers prepare for the battle, all the way through the fighting itself. Kambei lays out the strategy; he prepares the farmers with the aid of the other samurai; and keeps track of how things are going. With each wave, he marks off another tick for a bandit they’ve killed. One by one, they pick them off. However, the more they kill, the more they lose, and one night, it is difficult for villager and samurai alike to keep spirits up. But Kurosawa, though a realist by nature, was hardly a person obsessed with dreary subjects, and there’s much enjoyment to be gained in “Seven Samurai.” He even includes a love story between one of the samurai and a village girl. In reality, they could never be together, but Kurosawa made this film for modern audiences, and he allows the older characters a chance to reflect, and see that the love these two carry for one another, regardless of social station, should be allowed to blossom.

Watching “Seven Samurai” now, it’s easy to see the conventions that Kurosawa inadvertently established for the genre to come, yet his original effort overflows with life and dramatic tension because of the sense of purpose his film shows. It wasn’t just about thrilling an audience like it is with so many action films now; instead, Kurosawa was filtering the action, the narrative, through his own worldview, which starts off by adhering to the traditions of the characters he is telling a story about, but gradually shows them breaking from their tradition in a way that is important for the larger society. To his detractors, especially in his home country, this made him too Western a director, but by bringing his own morality and perspective to a story akin to the western films he loved, yet steeped in the traditions he was raised on, he formed an aesthetic that would influence cinema, and filmmakers, for generations to come.