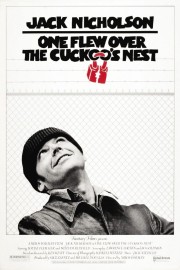

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

“One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” one of only three films to win all five major Oscars (Picture, Director, Actor, Actress, Screenplay), is what I would call an “official masterpiece.” For those who haven’t seen me use the phrase before, it refers to a film that has stood the test of time, and people acknowledge as a classic, whether they’ve actually seen it or not. I’m pretty sure the only time I saw it was in health class in high school, but it’s possible I saw it again in college, when I was really starting to watch movies. But the most memorable time, regardless, was that first time, and about 20 years later, and just short of 40 years since it came out, it’s time to revisit it.

I’ve discussed in these reviews how I’ve dealt with depression, stress and anxiety for a lot of my adult life, if not my entire life. It’s led to some difficult times in my life, and some fractured friendships over the years. It also led to an important moment when I decided to take action and learn to control those emotions, and where they were coming from. I never found myself in a mental institution like R.P. McMurphy, to be sure, but I’ve done both group therapy and individual sessions, and I’ve got to say, I’m grateful I’ve never had anybody like Nurse Ratched treating me. Of course, this film isn’t about mental illness, per se, though it certainly can be beneficial in looking at troubled minds.

Based on a novel by Ken Kesey, and featuring a sharply funny screenplay by Bo Goldman and Lawrence Hauben, the film follows R.P. McMurphy (Jack Nicholson, in the first of his three Oscar-winning performances) as he is transferred from prison (where he was serving time for statutory rape) to a mental institution. The prison thinks he’s faking, and some of the doctors do, as well, but there is a way things are done, and McMurphy was sent to them for a reason. That starts to look like a mistake early on. McMurphy is a rambunctious, defiant personality, and it’s not long before he has the inmates gambling, speaking up, and gets them out of the institution on a fishing trip and demanding to watch the World Series. On the surface, the institution has their hands full as a result of McMurphy’s insolence, but the head nurse, Nurse Ratched (Louise Fletcher, an Oscar-winner along with Nicholson), will not be broken, and will get things in order, by whatever means she is afforded. In a more compromised movie, Jack would obviously prevail, but McMurphy isn’t Jack, regardless of how effortlessly the performances defined Nicholson’s career from that point forward.

The film is directed by Milos Forman, the Czech director who immigrated to the United States, and gained much acclaim films ranging from “Cuckoo’s Nest” and “Amadeus,” both of which won the director Oscars, to “The People vs. Larry Flynt” and “Man on the Moon.” The common thread in his films in the US is that they involve outcasts who buck the system, and are nonconformists in every sense of the word. They rebel against the conventions of the society they live in, and make a lasting impression on the people they come in contact with. They may not be appreciated by the people they answer to, but each one blazes a trail for future rebels, whether it’s the composers inspired by Mozart in later generations or comics like Jim Carrey and Sacha Baron Cohen whose work owes a debt to Andy Kaufman, or Chief (Will Sampson) in “Cuckoo’s Nest,” who has been playing deaf and mute throughout his time in the institution, but opens up in ways nobody else can understand to McMurphy. McMurphy may be a fictional character, but he’s just as inspiring to those of us who feel the urge to rage against the system as any of the real-life people Forman has chronicled in his career.

It’s in the performances where “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” truly flies as filmmaking, though, although producer Saul Zaentz has all cylinders firing on the film, from composer Jack Nitzsche and cinematographer Haskell Wexler to editor Richard Chew. Nicholson is the obvious MVP, and rightfully so, but it’s impossible not to point out the icy resolve of Fletcher’s Ratched, who is just as repressed as McMurphy is liberated. The supporting cast, though, isn’t a slouch: Sampson hits the most layers of pathos as Chief, especially in the haunting final moments where he fulfills McMurphy’s dreams for them both, although more recognizable faces (like Danny DeVito as Martini, Brad Douriff as Billy, Christopher Lloyd as Taber, and Vincent Schiavelli as Frederickson) certainly do great jobs in their roles. It’s the faces no one forgets in “Cuckoo’s Nest,” and those faces are windows into characters who are more than the diagnosis that defines them in this film. It’s an unforgettable ride, even if it doesn’t end quite the way we hope.