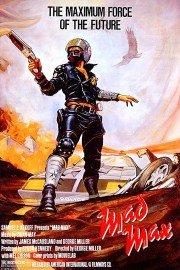

Mad Max

My image of Max Rockatansky, whom audiences know affectionately as Mad Max, is so dominated by the way the character is in “The Road Warrior” that seeing him as a family man and joking around with his fellow officers in 1979’s “Mad Max” is a bit of a surprise. By the time “Road Warrior” starts, Max is hardened, violent and uncontrollable. In a way, this is the opposite of the evolution Martin Riggs, Mel Gibson’s character in the “Lethal Weapon” series, underwent, where the character started out hollow and became human throughout the course of the series. The fact that Gibson could play both emotional ranges effortlessly made it no surprise that he became one of the biggest stars of the ’80s and ’90s, with these two franchises being the cornerstones of his stardom for many years. Today, however, I’m only focusing on his breakout film, which is about to have it’s third sequel released this Friday.

The driving force of “Mad Max,” and the subsequent franchise, is not so much Gibson, however, but the vision of co-writer/director George Miller, who has made all four films in the series. Recently, Miller has been known for family films such as the “Happy Feet” animated movies (which he directed, and won an Oscar for the first film) and the “Babe” films (he produced the first one, but directed the second), but it’s his “Max” series that will define his legacy as a filmmaker. For most audiences, the high-water mark of car chases and action scenes are the “Fast & Furious” movies, but rewatching Miller’s magic in this first film, and thinking about “The Road Warrior,” only illustrate how much later films owe to the clarity of chaos Miller has in store in these films.

The screenplay by Miller and James McCausland isn’t complicated, but it doesn’t need to be. The film starts off with a high-speed chase in a land in the not-too-distant future between cops and a criminal known as Night Rider and his girl. After his fellow officers are out of commission, Max takes over the hunt, and it’s not long before Night Rider is dead, and while Max is celebrated for his work, he also has a target on his back as a result from the gang, led by the ruthless Toecutter (Hugh Keays-Byrne). That target extends to his friends and family, and after one of his friends is attacked and burned by the gang, Max quits the force for the safety of his wife and their young child, although even that might not even help.

What propels this story is the action, and while Miller went bigger, and better, in “Road Warrior,” the chase sequences, and how they fit into the narrative, are no less impressive. Apart from the excellent stuntmen, the MVPs of these sequences are cinematographer David Eggby and editors Cliff Hayes and Tony Paterson, who realize Miller’s vision in a way that makes absolute sense visually. The problem with a lot of the scenes from the “Fast & Furious” and “Transformer” movies is not so much anything technical but that from a filmmaking standpoint, they lose focus and don’t really orient the viewer to what they’re watching. Not so with Miller’s sequences for the “Max” movies, which is why it’s not nothing that he’s directing this year’s “Fury Road.” He understands action filmmaking not just on a technical level but a storytelling level, and how the juxtaposition of shots in a particular order, as well as the type of shots, have a particular emotional impact on the viewers. A carefully placed close-up can add profound meaning to an action sequence– it’s not just about apocalyptic chaos and mayhem (hear that Michael Bay?). The best action is less about the action itself but about how the characters are developed through the action on-screen, and Miller is one of the all-time masters in that department.

The setting of “Mad Max” may be desolate and primitive, but how those conditions, and what happens throughout the film’s 94 minutes, are important to how we identify with Max and become engaged in his story, and that’s where Gibson comes in to take us home. “Mad Max” was only his third film, but already, Gibson had something about him that assured his rise to stardom. Max was a perfect role to put that on display, as we see Gibson as not just a loving family man with his wife and son, but also as a single-minded madman when they’re threatened. This role set the template for a lot of Gibson’s most memorable characters in the years to come, and given how much we’ve seen Gibson’s personal demons come out in recent years, it’s not hard to see why he is so at home in both personas. Mad Mel was always a bit different than his contemporaries in how that dark side came out in even his heroic roles, and it’s part of why villain roles (like he’s taken on in “Machete Kills” and “Expendables 3”) might be his road back to the good graces of audiences, and his fellow filmmakers, after the darkness that’s ruined his life the past decade. It’s too late for “Fury Road,” but if Miller gets a chance at a fifth “Max” film, it might be good to see Gibson go after the new Max, Tom Hardy, in a battle royale in the Australian Outback. I’d pay to see that in a heartbeat.