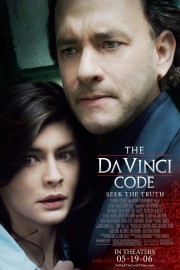

The Da Vinci Code

**#5 on Brian’s “Must-See” List for Summer 2006**

If past history has taught us anything, it’s that the far religious right- and their followers- will get stirred up by any movie about religion that stirs things up with ideas that cause actual thought about this touchiest of subjects. Movies like “The Omega Code” and its’ sequel “Megiddo” (saw the former, not the latter), the adaptations of the “Left Behind” novels (which I’ve never seen nor read), and “The Gospel of John” (which I never saw when we had it at the theatre)- these movies appear to be made by believers and present issues of faith in ways that are not threatening to the “Powers That Be”- so to speak- that preside over matters of faith on Earth, be they actual ministers, priests, or leaders in the Church or political pundits or lobbyists looking to further their agenda.

Fair enough. But these films can be devoid of interest for those of us- like myself- who don’t hold to any particularly strong religious beliefs and/or are open-minded enough to embrace any film that inspires complex thought about religion, faith, and spirituality (I couldn’t get into “The Omega Code,” which was the first modern film to become a box-office success- albeit a modest one- because of grass-roots campaigning towards the intended audience). For me personally, Andrei Tarkovsky’s “Andrei Rublev,” Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ,” Martin Scorsese’s “The Last Temptation of Christ” and “Kundun,” and Kevin Smith’s “Dogma”- all made by true believers I might add- are films that, in their own singular ways, approach religion in not only a reverent way but also a challenging way, inspiring legitimate thought about what it means to have faith and believe in the existance of a higher power, with a higher purpose in mind, and how that faith can exist even when it exists apart from the accepted dogma of the Church. All of these films were met with harsh criticism by religious groups at the time of their release (though “Rublev’s”- made and released in Soviet Russia- was experienced more in its’ country of origin than it ever was here), none more so than “The Last Temptation of Christ,” which was deemed so blasphemous that leaders on the right offered to buy the movie from Universal and destroy it; all- save for “Passion” (which I’m holding off on in case Fox double-dips on the DVD release)- are in my collection.

All that said, were you expecting a different reaction regarding “The Da Vinci Code?”

I have not read Dan Brown’s novel, which bacame a mega-blockbuster in 2003 while also fueling much debate and controversy about its’ ideas- more on those in a moment. First, I’m not much of a reader, though the films based on/inspired by “Lord of the Rings” and “I, Robot” caused me to pick up those books and speed through them either after the films or prior to them. But also, I remember loving going into “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone”- and the three “Potter” films since- without the advanced knowledge of the story’s specifics and becoming fully engaged in the story nonetheless. It’s been harder to avoid spoilers about “Da Vinci,” but though the film takes a little too long to tell its’ story (at 149 minutes, it was probably stretched a little too much given the type of story it is), but in the capable hands of screenwriter Akiva Goldsman (“A Beautiful Mind,” “The Client”) and director Ron Howard (“A Beautiful Mind,” “Ransom,” “Apollo 13”), “Code” churns out some smart, provocative thrills for a story that’s fundamentally a popcorn entertainment in the vein of the Indiana Jones movies (especially “Raiders of the Lost Ark”) and 2004’s underrated “National Treasure,” which took some cues from “Da Vinci” in the way it ties in real-world facts, places, and items into a cleverly-constructed fictional mystery/adventure.

And it is important to realize that “The Da Vinci Code” is a work of fiction. There’s probably as much truth to most of Brown’s conceits in this story (the most controversial of which, actually, is depicted in “The Last Temptation of Christ” as well; if you’re familiar with both, you know what I’m referring to) as there was to the idea of a Golgothan shit demon or the 13th apostle (played by Chris Rock) who was left out of the Bible because he was black in “Dogma.” Like Smith in his comic take on a war between Heaven and Hell, Brown- and for the film, Howard and Goldsman- presents bold ideas as a way of searching for a deeper emotional truth in the pursuit of discovering one’s own level of personal faith. Perhaps that’s looking too deeply into the story, but the best films where faith is explored in purely religious terms, as I said earlier, are the ones that inspire the deepest thought about their themes and stories. And while “The Da Vinci Code” is more of a secular way of looking at those themes, it nonetheless examines them with a deeper intelligence than we’re used to in Hollywood escapism.

So what’s the story already? You probably already know, but here’s a brief, spoiler-resistant summary. It starts with a murder in the Louvre, which symbologist Robert Langdon (Tom Hanks, a little more dour than we’re used to, but engaging nonetheless) is brought in to advise one. That sets into motion a chase story where he and French police cryptologist Sophie Neveu (“Amelie’s” Audrey Tautou, struggling to inject feeling in her performance while speaking English- not an easy task; the more English-fluent Julie Delpy (“Before Sunset”) would’ve been a better choice under the circumstances) are on the run from not only a rogue French policeman (Jean Reno, great at playing deceptive characters; see “The Professional” and “Mission: Impossible”) but also a consortium involving an assassin albino monk named Silas (Paul Bettany, more genuine in his haunting performance than some critics I’ve read have given him credit for) that’s part of an ultra-conservative group known as Opus Dei and whom commits brutal acts of self-flagellation, and a bishop (Alfred Molina, who makes an impression with limited screentime) who is one of a handful of Catholic leaders out to ensure a potentially-damaging secret about the beginnings of Christianity and the personal life of Christ is never revealed. The clues lead Robert and Sophie closer to that secret and a devout believer in it in Robert’s friend Sir Leigh Teabing (Sir Ian McKellen, playing the role with just the right blend of subtle gravitas and zealot’s intensity). From there, you’re on your own if, like me, you haven’t read the book.

In close examination of the story, it’s not hard to see how “The Da Vinci Code” became such a hot-button issue for religious hard-liners, and even some ordinary churchgoers. But in the end, “Code”- be it in Brown’s text or Howard’s movie (shot by cinematographer Salvatore Totino and scored by Hans Zimmer to maximum effect of mood)- is a piece of speculative escapism, and a damn good one at that, to be enjoyed as such. That it’s provoked such feelings is an example of what the best fiction is capable of. That it deserves such discussion- one could debate whether it’s been thoughtful or not (though from articles I’ve read it has inspired some)- is a credit to the creative individuals who’ve brought the story to life for people who’ve opened their minds to the ideas it presents. By all accounts Ron Howard’s “The Da Vinci Code” fails to live up to its’ literary predecessor, but how many adaptations can claim such excellence in the first place?