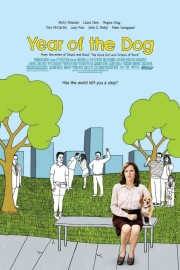

Year of the Dog

Peggy is a woman happy in her insular world. She gets up, goes to work, does her job, comes home to her dog Pencil, and goes to bed. It’s a simple life. She has friends and family who care, whom share things of their own lives with her, and she listens with a friendly ear. It’s a simple life to be sure, but it’s a happy life.

And then her dog dies. The thing to understand most about Peggy’s life is that her love for Pencil- and his unconditional love back- is what made her whole. She had the type of relationship with Pencil that other people may have with other people, may have with even things. It’s a bond that’s difficult to quantify into words, especially for a person with few real person-to-person connections that go beyond mere acquaintances, and even with her closest friends and family, she’s likely to be very reserved about talking about herself, especially if it’s because she doesn’t have anything much going on to talk about, which is often. When the outside world intervenes in it, well, it tends to throw things off…way off.

Peggy is played at just the right note of loneliness and awkwardness by Molly Shannon in “Year of the Dog.” It’s the first time out as a director for Mike White, the talented screenwriter whose script for “The Good Girl” hit upon a similar tone of melancholy and social commentary while providing a character study of its’ main character (look again at the film, and find how the routine of Jennifer Aniston’s life is upended by the outside world in much the same way- albeit with different results (and different challenges)- Peggy’s is). That’s not to discount White’s other writing efforts- “Orange County” is one of the best modern teen movies around, and “School of Rock” was a tour de force vehicle for Jack Black (the less said about “Nacho Libre,” the better)- but, perhaps because both main characters are female, and that both films are about unexpected times of change for the characters, there’s a certain level of kinship between the two films that’s undeniable for fans of White’s work. His work behind the camera doesn’t distract from the story, but neither does it really add anything to it (and Christophe Beck’s score seems to work overtime to do so while also apeing the quirky sensibilities of Rolfe Kent). His script is what does the heavy lifting, and it’s successful at both thrusting us into Peggy’s life, and creating a set of supporting characters that illuminate what she’s missing in her life while also throwing it for a loop by what they don’t understand about it.

But one look at Peggy throws you a question…was she really missing anything in her life? Conventional society would say yes, as she appears passive in her interactions with those around her, be they her boss (Josh Pais, just as awkward as she is); her protective brother (a touching and subtle performance by Tom McCarthy) and his sweet, but somewhat oppressive wife (Laura Dern, in as much a 180 from “INLAND EMPIRE” as you can imagine- a true sign of her versatility); and her best friend at work (Regina King, ever the standout), who’s looking to tie the not with her not-so-trustworthy boyfriend. But Peggy’s face as she listens to their concerns about their own lives shows she cares, even if she can’t relate.

However, no matter how sympathetic any of them are, they can’t quite understand how much Pencil meant to her. That’s the cue for two new additions to her social circle; Al, the rugged next-door-neighbor (played by the reliably good-natured John C. Reilly) who knows what it’s like to lose a pet…even if his carelessness was the reason for the loss (he accidentally shot his childhood dog on a hunting accident); and Newt, a sensitive worker at the pet clinic Peggy takes Pencil to (played by Peter Saarsgard in a performance no less impressive than his more dramatic work in “Jarhead,” “Kinsey” and “Garden State”) who opens her eyes to Veganism, animal activism, and finds her a new four-legged companion in Valentine, an ironic name given the dog’s inability to play well with others. Peggy feels an immediate connection with Newt that goes beyond their mutual love of animals; her awkward reveal of her deeper feelings- and his rebuke of them- forces her back into her shell, and only confirms for her the notion that people have always disappointed her, while animals never will. Along the way, Al will have proven as much as well, but as much for his appreciation for hunting as for her suspicion that something in his garage- whose door was open the night Pencil died- was the cause of Pencil’s death.

It’s easy to understand why people might consider Peggy troubled, and indeed she perhaps needs counseling. But when a person’s lived so long the same way, anything new or unexpected that upsets that way of life is a scary proposition, and Peggy’s discomfort as a result is spot-on in Shannon’s endearing and sympathetic performance. You see Peggy trying to open up to these new possibilities, only to revert to form when they don’t work out. It’s a natural response for those of us who are socially awkward to find solace within ourselves, the routine that brought us so much joy and so little pain, when the new brings us pains that we’d rather due without. Though alone in life, Peggy’s very much a person dependent on others- and the things she’s been able to lean on for comfort over the years- in order to exist. She doesn’t do it out of malice or spite, but out of a basic human need for acceptance, and a purpose in life beyond herself (which White outlines deftly in the satisfying ending). It’s not meant to be selfish, even if it can appear that way to the people around her. In that respect, she’s not really unlike a dog, which are here for our benefit, while also rely on us for their survival. That’s intended to be a compliment from someone who understands her dilemma, and feels her pain.