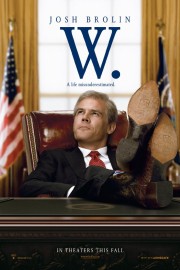

W.

When one first hears of the idea of a film about George W. Bush being directed by Oliver Stone, the first instinct for right-wingers is to call foul- this is the conspiracy-driven firebrand responsible for “JFK” after all. For left-wingers, it’s a prospect that also brings to mind his revolutionary masterpiece “JFK,” but for a different reason. They remember the fury and frustration surrounding the assassination of President Kennedy the film generated with a liberal slant on the facts. for us liberals, we can’t help but go in expecting him to blow the lid off of the whole shebang, slamming Bush and co. with the same degree of force Michael Moore did with “Fahrenheit 9/11.”

Well, surprise for people of both sides- Stone is nothing if not unpredictable. Working from an acute and sometimes eccentric-minded script by his “Wall Street” writer Stanley Weiser, Stone has crafted a film not aimed towards sucking up to the extremes but giving Bush- a fellow Yale man- a fair shake. Which means no “My Pet Goat” recreation. No Hurricane Katrina and “You’re doin’ a heck of a job, Brownie.” No 2000 campaign controversy, and very little of the aftermath in Iraq post-“Mission Accomplished.” That approach alone makes the film better than it should be- a partisan handjob in either direction would have seemed par for the course and more biased.

My dislike of the Bush administration and its’ policies is well-known to faithful readers. That said, the trailers for “W.” were nonetheless intriguing. Instead of the politics, Stone was looking to get to the bottom of the man. The result could’ve been as boring and tame as “Alexander,” and make no mistake, “W.” has its’ fair share of biopic pitfalls, but the subject alone makes it quite absorbing as human drama. It shows Dubya as a drifting rebel and driven political leader, a boy whose made mistakes and a man looking to atone for them. More than anything else, it gets us into the head of someone dealing with a lot of the same tough times and emotional hangups we all do. By the end, we come pretty close to actually feeling sorry for him, regardless of our political affiliation.

For that, “W.” owes much of its’ success to Josh Brolin, whose star has risen over the past year with performances in Robert Rodriguez’s “Grindhouse: Planet Terror,” Ridley Scott’s “American Gangster,” and the Coen Brothers’ Oscar-winning “No Country for Old Men.” With “W.,” as Dubya, Brolin raises his game to higher levels than even those impressive credentials. Going beyond simple impersonation, Brolin’s Bush feels lived-in, with the actor getting to the conflicted heart of the Bush family’s black sheep, be it his hard-drinking, harder partying youth where he was a C-student at Yale and a fuck-up in holding a job, his transition from youthful rebel to born-again Christian, and finally his ascendancy to the Presidency, where his lack of common-sense intelligence and his appointment of old-party ideologues leads to misjudgement the country is still paying for when it comes to Iraq.

But all the while, deeper story seeds plant themselves as we witness Dubya through the eyes of his stern father George H.W. Bush (James Cromwell) and his sterner mother Barbara (Ellen Burstyn). Was Bush’s political aspirations “a call from God,” as he has said and the film dramatizes (albeit with one of its’ juiciest punchlines when W. consults his pastor as he contemplates the presidency), or was it to simply get his father- who has a clear bias towards his brother Jeb (who was Governer of Florida during the 2000 election)- to be proud of him? Admittedly, the film lays things on this front a little thick near the end (especially during a needless dream sequence), but would it be an Oliver Stone movie if there weren’t a little heavy-handedness? (Although his 2006 film- the greatly underappreciated “World Trade Center”- largely lacked “the grand touch,” and was a better film for it.) Nonetheless, Brolin and Cromwell- who embodies Bush Sr. well enough, but one wonders whether a different casting choice could’ve been better- make this father-son relationship bristle with familial tension, with Burstyn- in a thankless and underdeveloped role- occasionally piping in for some biting remark at either man, although some sympathy is shown by the former First Lady.

As with “World Trade Center,” “Born on the Fourth of July,” and “Platoon,” Stone’s technical gifts- seen in overdrive with the masterful “JFK” and the mindnumbing “Natural Born Killers”- are largely absent, in favor of a more straight-forward storytelling approach (although the film’s jumps through time periods can become somewhat confusing, even though years are provided in the bottom left-hand corner). Again, the approach serves the film well- there’s no need for the technical overload with a story like this (even though the close-up cinematography by Phedon Papamichael (whose resume includes a variety of projects from “The Weather Man” to “3:10 to Yuma” to “Patch Adams”) doesn’t always hit the mark Stone would prefer). This film is about characters, situations, and capturing the essence of a man about whom everyone generally has an opinion of. In that case, the film succeeds wonderfully…

…especially when you see Bush’s interactions with those around him. Most prevalent are his parents, of course, but there’s also his wife Laura- a democrat when the two met, and a fervent supporter of her husband, truly for “better or worse” standing by her man. This has been a breakthrough year for Elizabeth Banks (whose resume this year has also included “Definitely, Maybe” and Kevin Smith’s upcoming “Zack and Miri Make a Porno”), with her performance as the current First Lady- albeit less-prominent than you’d prefer- nonetheless making her- like her onscreen husband- an actor on the rise. In his White House inner circle, Thandie Newton inhabits brilliantly- down to the mannerisms and voice- current Secretary of State Condi Rice; Scott Glenn finds the sleaze behind former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld as he sells Bush on Iraq; and Jeffrey Wright finds the honor and conflict behind former Secretary of State Colin Powell, who became something of the Administration’s sacrificial lamb after taking the floor of the U.N. to sell the prospects of an Iraq War to the world. Most noteworthy of all are Richard Dreyfuss, who embodies the hard-line deception and secretive nature of Vice President Dick Cheney- a Nixon Republican whose power and influence has been arguably among the strongest of any V.P. in history- especially during a lunch discussion with Bush that involves Bush signing the order on interrogation tactics to be used at Gitmo, and Toby Jones as Karl Rove, the political strategist whose infamously dirty campaigning techniques- which helped Bush in his bids for both President and Governor of Texas- are still seen today, even after his forced resignation in 2007.

One of “W.’s” most intriguing questions it poses, and where much of its’ post-viewing strength lies, is the question of how Bush’s Administration has sunk so low in its’ policies, while one of the most intriguing questions we may ask of the film is its’ lasting impression as the years go by and people unfamiliar with the past eight years begin to see it. In other words, will it be seen as a timeless chronicle of the life of one of our most controversial political leaders, or will it be seen as simply a convoluted and forgettable effort to get to the bottom of the man? But as Bush famously said when asked about how history would view him, “History? In history we’ll all be dead!” Still, that doesn’t mean the ramifications cannot be considered (one historian, Sean Wilentz, has already taken to the pages of “Rolling Stone” to contemplate the Bush legacy; it isn’t a pretty picture). Has Bush been the raging ideologue the extreme left like to paint him has, or has he simply been pushed in that direction by the people he surrounded himself with, many of whom were in his father’s own administration? “W.” doesn’t have all the answers, but that it chooses to ask the question is probably the greatest sign of the film’s worth.