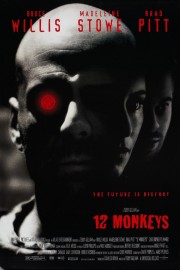

Twelve Monkeys

Sometimes, great films take time to achieve universal greatness. Hitchcock’s “Vertigo” comes to mind. Admittedly, a lot of the reason I bring up “Vertigo” is because Terry Gilliam’s “12 Monkeys” references Hitch’s masterwork both onscreen- Bruce Willis and Madeleine Stowe hide out in a theater playing it- and visually in a flashback that is seen frequently throughout the film. In it, a young boy witnesses a shooting in an airport. A mournful violin plays over the flashback, and Gilliam focuses on the boy’s eyes, so sad, as if he knows in that instant what the future holds for him.

Like Hitchcock’s film, Gilliam’s 1995 thriller has only gotten better with age- richer, more evocative. Like another film that’s come to mind since seeing “Watchmen” last week- Alex Proyas’ “Dark City”- Gilliam’s film is a visionary accomplishment. For Gilliam, who- since starting his cinematic legacy with Monty Python in the ’70s- has had a spotty, but admirable, directorial career that includes cult classics like “Brazil,” “The Fisher King,” and “Time Bandits” and less-acclaimed efforts like “The Brothers Grimm” and the unsettling but fascinating “Tideland,” “12 Monkeys” is a visual and emotional milestone. Working from a screenplay by David Peoples (“Blade Runner,” “Unforgiven”) and his wife Janet- who took the idea from an avant garde short film by Chris Marker called “La Jetee”- Gilliam is more fascinated by the psychological toll of time travel than the traditional wham-bam action side of sci-fi we’re used to.

The year is 2035. Mankind is very nearly extinct after a deadly virus is unleashed, resulting in the death of five billion people. The survivors now live underground, with animals now in charge on the top. The dystopia Gilliam and cinematographer Roger Pratt and production designer Jeffrey Beecroft create feels more organic, and thus unnerving, lacking in the stylized touches of “Blade Runner” and “Dark City,” although it’s just as dangerous.

James Cole (Willis) is a prisoner in this world- violent, scarred by childhood traumas he doesn’t yet understand- and thus a prime candidate for “volunteering” to help the scientists in charge, who are exploring the animal world above in an attempt to get back on top of the planet. After one such mission, the scientists decide they can count on Cole for a bolder mission. They thus decide to send him to the year 1996 on a fact-finding mission to track the virus at its’ origins in hopes of learning more about it to get them back to the surface, which is still uninhabitable for man (the outfit Cole must wear on the surface is an ingenious getup). But as a mysterious, gravelly-voiced observer tells Cole, “science ain’t exactly an exact science with these clowns.”

Cole is inadvertently sent back to 1990, where he is quickly arrest as a vagrant, and sent to a mental institution in Philadelphia. There he meets Dr. Katherine Reilly (Stowe) and Jeffrey Goines (Brad Pitt), two characters whose destinies will be forever changed through their encounters with Cole.

Reilly is a compassionate, but highly logical, psychiatrist who is fascinated by Cole as a case study, but- when the two meet up in 1996, when Cole (whose sudden disappearance from the hospital back in ’90 puzzled her and her colleagues) kidnaps Katherine after a lecture- will become more emotionally caring for him when they find themselves on the run. Cole and Katherine’s bond is the heart of the movie, with both characters questioning every impulse they’ve had as their situation feels more like deja vü than coincidence, and Willis and Stowe deliver some of the best work of their careers as these two move beyond patient-doctor and begin to care for each other in the same way Jimmy Stewart and Kim Novak- themselves both scarred characters at the hands of something more than coincidence- did in “Vertigo.” For some, the parallels drawn by Gilliam and the Peoples’ will strike a chord of heavy-handedness, but when we finally see the full significance of Cole’s dream- with a younger him witnessing tragedy at an airport- we can’t help but be swept up in the same romantic tragedy Hitch achieved in his film.

Cole’s trips back in time- including an unexpected stop in a French WWI bunker- lead him of a search for the Army of the 12 Monkeys, which could hold the key to how the end of the world happened. The leader of the group- originally just an organization that picketed the use of animals for scientific experimentation- is Goines, although when Cole first meets him, he is in the same mental facility Cole is taken to. Goines is the son of a Nobel-winning scientist (Christopher Plummer), but even when we see him later in the film, he’s a bit of a loose cannon in body and mind. This was Pitt’s first big breakthrough from the Hollywood star he became with “Interview With the Vampire” and “Legends of the Fall” (even David Fincher’s gritty “Se7en” still had the actor in major star mode), and a sign of the delicious anarchy to come in films as diverse as “Fight Club,” “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button,” “Burn After Reading,” and the “Ocean’s” films. As Goines, he hits all the right notes as an unhinged mind let loose in the funny farm in a performance as frightening as it is funny.

It’s that combination of dark comedy and dark drama that comes to define many a Gilliam film. “12 Monkeys” is no different, with a score by Paul Buckmaster that captures that manic tone and the foreboding sorrow we feel as the climax comes down on the film’s characters, and the human race. What makes “Monkeys” anything but the usual monkey business for Gilliam is a feeling of lost hope and romantic chivalry that is unlike anything we’ve seen from the director outside of his underrated “Fisher King.” As you get to see Gilliam work in the outstanding documentary that accompanies the film on DVD (by the same people who made the tragic-funny “Lost in La Mancha”), it’s not hard to see a little of that uncertainty about reality Cole feels in the film’s director. That he succeeded in spite of that uncertainty is anything if not a Hollywood miracle.