The Trial

The more one delves into Orson Welles’ cinematic career after his 1941 debut “Citizen Kane”- you know, the one everyone and their mother in cinema calls “the greatest film ever made”- the more you see how Welles pushed the boundaries of storytelling even further as he got further away from “Kane” in his career. True, he rarely had the freedom he had on “Kane” after that film’s blistering debut, but you can see his free-wheeling spirit alive and well in so many films afterwards, be it the 1958 noir classic “Touch of Evil” or his 1974 free-form film “F for Fake”…

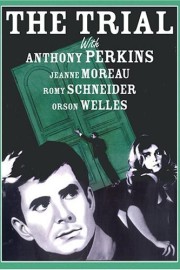

…and then there’s “The Trial.” Backed by Alexander Salkind (who produced the first “Superman” movies with Christopher Reeve), Welles enjoyed absolute freedom in adapting Franz Kafka’s iconic novel about Josef K, a bureaucrat who wakes up one day only to find that he’s been accused of a crime. But what crime? As he follows the labyrinthine path towards a final verdict, Josef K gets pushed and pulled in a variety of ways- by women, by authorities, by his family- that all adds to the anxiety and paranoia of his dilemma.

Welles sets the stage early, in a thematically-intriguing story of a man sitting outside of the doors of the law. He is persuaded not to enter by the guard, who tells him that through that door is another door, with another guard, even more powerful than he. Years go by, and the man stays outside the doors. At the end of his life, the man is frail and little more than a skeleton. He asks the guard one last question- “Why hasn’t anyone else tried to enter to see the law?” The guard says, “Because everyone has their own door. This was to be yours. And now, I can close it.”

This anecdote- evocatively drawn, and narrated by Welles in that classic baritone- sets the stage for Josef K’s dilemma. Kafka’s surrealist narrative has inspired many an artist and filmmaker over the years- through Welles’ adaptation, you can see the future triumphs of Kubrick, Proyas, Bunuel, and Lynch. Welles sees Kafka’s vision of an individual’s paranoid world clearly, fearlessly following Josef K into this maze of uncertainty as he pleads his innocence while trying to figure out what exactly he’s being accused of. His film is above all a visual triumph, with the “found sets” he was forced to use casting shadows all around Josef K, as he moves from one seeming dead-end to another, searching for answers that always seem just out of reach.

I can see a lot of people giving up on this film, as the story moves briskly and without much resolve for clarity as K- played by Anthony Perkins in a performance that is the equal to his role in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho”- goes from room-to-room, interaction to interaction, trying to get down to the bottom of things. It’s only when he sees The Advocate (played by Welles himself) that we begin to see some resolution. But even as K is taken to a quarry, sentenced to die for reasons still unexplained to him, “The Trial” remains an elusive mystery. We remain sympathetic to him, hoping to never find ourselves in such a position of being assumed guilty for no reason whatsoever. It’s easy to see what drew Welles to this material- by this stage of his career, one can see him searching for answers as to what fate brought him to this place where he had to scrounge for budgets years after Hollywood came knocking on his door.