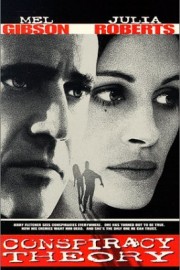

Conspiracy Theory

The opening credits set the tone. Actually, it’s the music. Jazzy, mysterious, evocative of various moods and feelings. Suspenseful, yet comic. And then, the brass comes in, the percussion picks up the tempo, and off we go.

How Carter Burwell has gone unrecognized by peers and critics over the years is beyond me- his work with the Coen Brothers has always delivered an extra dimension to their darkly comic concoctions. But it’s in the opening sequence of Richard Donner’s smart and sharp “Conspiracy Theory” where Burwell really lets it rip. The opening credits are like the opposite of those for Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver,” with Mel Gibson’s Jerry Fletcher spouting out theory after theory to customer in his cap, the credits being seen in the water on the road, in the windshield, everywhere a neon light might shine on the mean streets of New York.

Burwell carries the film on the tip of his baton, with his music recalling both Herrmann’s sinuous work on “Taxi Driver,” not to mention his more infamous work with Hitchcock. In more ways than one, Donner- a sharp craftsman with plenty of good films to his credit (see the “Lethal Weapon” series, “Superman,” and “16 Blocks”)- is finding his inner Hitchcock in bringing Brian Helgeland’s sly script to the screen, with a love story between Gibson’s paranoid cabbie Fletcher and Julia Roberts’ work-a-bout Justice Department attorney Alice Sutton at the center of a mystery-thriller that plays like an updated version of Hitchcock’s classic story crisis, of an innocent man, wrongly accused.

But how innocent is Jerry? His longing for Alice is from afar, as he watches her in her apartment from his cab, watching her sing to the music as she exercises. He saved her life six months ago when she was mugged, but had he known her before that day?

Fitting for the film’s title, a lot of theories about Jerry, and from Jerry, seem to have some kernel of truth to them, especially when a mysterious Dr. Jonah (Patrick Stewart, playing against his noble image, using his mind and cunning as a deadly weapon) abducts him, torturing him- “Clockwork Orange” style- before Jerry can make a clever and accidental escape.

Considering his recent personal issues, it’s not hard to see some more identifying between actor and character in “Theory” than there was in 1997, when Gibson was still one of the biggest draws in the world. Both share quirky personalities, as well as troubled pasts, Gibson’s more so now with recent controversies. The difference is, however, Jerry is a man of circumstance- in the wrong place at the wrong time, if you will- whereas Gibson’s are of his own making. Watching the film again, it’s easier to sympathize with the character than it is with the actor playing him.

Maybe that’s why Mel works so well in the role. He’s always been able to play outsiders and flawed characters better than any other star, probably because he shares their frailties, and lets his own come out onscreen. Regardless of how you view his personal life and his problems over the years, there’s little doubt of Gibson as one of Hollywood’s most underrated actors.

In Roberts, Donner found an ideal match for his frequent leading man (they made six films together over the years), and she turns on the star power as Alice Sutton. Still reeling from the mysterious death of her father a while back, Alice is skeptical of Jerry’s motivations to get to know her. She’s flattered, and she tolerates his unannounced visits to her office, but she’s just about at the end of her rope with his antics.

After he’s escaped from Jonah’s clutches, and makes his way into her building though, Alice lets her guard down, as Jerry’s frailties start to endure her to him, to want to help him. Roberts plays the change effortlessly, as much a tribute to Donner’s skills with actors as it is his actor’s prowess. Nothing feels forced- ok, maybe some of the humor- because everyone makes us feel it from the inside out. Even an impromptu trip into Jerry’s fortress-like apartment, filled with conspiracies, is more a window into a fragile mind than it is the acts of a lunatic. His collection of copies of “The Catcher and the Rye” is a bit unnerving- especially when you consider a couple of famous shooters who also owned the English class staple- but the book and its’ hero plays more like a parallel of Jerry’s alienation with society than it does the inspiration for a looney. But why does he feel compelled to buy so many copies of a book he has never read?

Admittedly, Helgeland’s script plays like a riff on every conspiracy thriller from John Frankenheimer’s classic ’60s films “The Manchurian Candidate” and “Seconds” to Oliver Stone’s “JFK,” but Helgeland plays with cliches like a pianist belting out a wild riff on a classic melody (it was a great prelude to his greater triumph a month later with Curtis Hanson’s “L.A. Confidential”), especially when Alice- otherwise a two-dimensional heroine- becomes the tougher character, not only emotionally but in personal courage. You’ll be cheering for her all the way by the end, as her and an FBI agent tracking Jerry (Cylk Cozart, turning a cliche into a truly entertaining character) uncover the truth, and realize they know more than they thought.

In the end, though, the film has always come down to the music in terms of why I love it so. Burwell’s score is an all-time fave, full of life and invention, and leaving us on the best of emotional highs by the end. Sure, the film plays it safe in the end- what do you expect from a big Hollywood film?- but is capable of playing it true, and not just true to what money men want to see. Same goes for the movie.