A.I. Artificial Intelligence

Originally Written: June 2001

This is one of those rare movies that- for me personally- inspires enthusiasm and excitement about movies. Let me go on record as to say this- some of you will dislike “A.I.” It’s inevitable. But those game for a summer movie that inspires more thought than thrills, more discussion than “Tomb Raider,” more feeling than “Pearl Harbor,” and more frustration than any Spielberg movie in 15 years (“Empire of the Sun”) will likely be rewarded. “A.I.”- for reasons I’ll discuss later- is an imperfect film, but not an impersonal one, and it’s the most ambitious sci-fi film since- approriately- “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

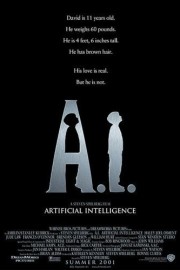

The polar icecaps have melted, and “mechas” (mechanics, or robots) and “orgas” (organisms, humans) are at odds with each other. David (Haley Joel Osment, “The Sixth Sense,” “Pay it Forward”) is 11 years old. He weighs 60 pounds. He is 4’6″. He has brown hair. His love is real. But he is not. This has been the cryptic description on the “A.I.” movie posters seen in many movie theaters this year, and for many, this might be all they know of the film. David is also the first robot programmed to love a human being, created at a time where childbirth is regulated, and- as David’s creator, Professor Hobby (William Hurt), says- he could fill “a great human need.” As a “trial run,” David fills that need for Henry and Monica (Sam Robards and Frances O’Connor), a couple whose only child Martin (Jake Thomas) has been cryogenically frozen, awaiting a cure for his terminal illness. Monica isn’t dealing well; Henry thinks David will do the trick. Monica at first resists “imprinting” David (activating his emotions), resulting in him following her around all day like a devoted puppy, mimicking her every movement (even at the dinner table, where he begins to laugh uncontrollably and unusually loud). One day, Monica decides to imprint (the catch though, is that once imprinted, it is irreversible, and David must be destroyed in order to deprogram), and in a spectacular bit of subtle acting, Osment tranforms from an emotionally sterile robot to the child Monica longs for.

All is serene until Martin is miraculously cured and returns home. David becomes jealous of Martin, eventually doing anything Martin says to try and regain Monica’s love. But after a couple of near-deadly misunderstandings, Monica and Henry decide that David is no longer welcome, and- in a heartbreaking scene- Monica abandons David in the woods like an unwanted animal. David assures her that- like Pinocchio in the fairy tale Monica reads the boys at one point- he can become a real boy too. “A.I.” then becomes an odyssey for David to find the Blue Fairy of the Pinocchio story so she can change him into a real boy. Along the way David inherits a friend in Gigolo Joe, a “love mecha” designed only to please woman played by Jude Law (“The Talented Mr. Riply”) in a vibrant, sly performance, whom he survives a “Flesh Fair” (a sort of bookburning rally by anti-mecha humans hosted by Lord Johnson-Johnson (“Braveheart’s” Brendon Gleeson)) with and leads him to Rouge City, where he finds answers about how to reach the Blue Fairy by the holographic Dr. Know (voiced by Robin Williams).

To say anymore of the story would be a disservice to the film, though I’m afraid I’ve said too much already. “A.I.” comes to us from two of cinema’s greatest artists- Steven Spielberg, who eventually wrote the screenplay (his first solo gig since “Close Encounters of the Third Kind”) and directed, and the late Stanley Kubtick. Kubrick was originally inspired to do a “family” film after seeing- no less- Spielberg’s “E.T.”. His choice of subject matter was Brian Aldiss’ short story “Super-Toys Last All Summer Long,” and in 1983, the long odyssey of “A.I.” began. Along the way, Kubrick commissioned artwork by comic book artist Chris Baker; enlisted the assistance of ILM’s Dennis Muren to learn the capabilities of CGI in realizing his vision of a submerged coastal city (we’ll get to that) and robot child; developed a treatment of the screenplay (which Spielberg eventually used to craft his own script); and even asked his friend Spielberg to direct the film, saying how it was “closer to your sensibilities than mine,” and envisioning the potentially-bankable possibility of “A Stanley Kubrick Production of a Steven Spielberg Film.”

Sadly, Kubrick was unable to see this dream through with his death in 1999. But through the encouragement of Kubrick’s wife Christine and her brother (Kubrick’s long-time producer) Jan Harlen, Spielberg committed himself to the completion of “A.I.,” shrouding the project in Kubrickian secrecy and mystery, which was further enhanced a couple of months ago with the emergence of an online murder mystery consisting of several interlocking websites and revolving around the film’s fictional “Sentient Machine Therapist” Jeanine Salla, providing the best use of the Web for movie marketing since “The Blair Witch Project” duped people into thinking the film was real.

It’s a shame Kubrick couldn’t see the final work, which is one of the most compelling works of Spielberg’s career. Contrary to early reviews, the film is not a “schizoid” collaboration of two very different directing styles, nor is it “Spielberg interpreting Kubrick” or “Kubrick informing Spielberg.” The visual logic of the film- editor Michael Kahn and cinematographer Janusz Kaminski- longtime Spielberg collaborators- match their remarkable work on “Schindler’s List” here- is purely Spielberg, albeit more the dark Spielberg of late (“Schindler’s List,” the shamefully underrated “Amistad”) than the commercial Spielberg of “Indiana Jones” and “Jurassic Park.” Strangely, I can’t really say that the John Williams score is anything but “schizoid”- at times traditional Williams (“E.T.,” “Star Wars”), at times more abstract and haunting (a scene near the beginning is a direct influence to the use of the “Gayane Ballet Suite (Adagio)” in “2001”). Still, an uneven work by a master is more compelling than formula from a hack, and Williams’ score is a must-hear on those grounds.

However, the subject matter and exquisitely-static art direction- and okay, the virtuoso tracking shots- are all the influence of Kubrick. It’s just noticable enough to be recognized, but subtle enough to avoid being distracting; it’s a high-wire act Spielberg pulls off brilliantly. He’s never done anything this audacious, as he combines the heart and humanity of his early fantasies (“E.T.,” “Close Encounters”) with the rigor of his recent work, all in the service of a purely Kubrickian subject that expands the man-and-machine interaction of “2001” to include genocide (a scene of a scrap yard of destroyed mechas- where damaged mechas replace parts- has the beguiling chill of the mounds of incinerated corpses in “Schindler’s List” through Kaminski’s brooding camera) and dangerous mecha-orga liasions in a middle-section that’s a flawed but fascinating glimpse of the world Monica never told David about. Some will carp that Spielberg doesn’t spend long enough examining the meach-orga division in this section, not to mention dodging the question of whether a human can love a robot that loves it once Monica strands David. Folks, he goes far enough with both; his focus is on David’s story, not a social commentary about the time he lives in. Maybe Kubrick might have made a more “2001”-ish social commentary, but we won’t know. Spielberg’s interest is in David’s journey to find his humanity, and for 140 spellbinding minutes, you won’t be able to talk your eyes off the screen…thanks to Osment, who’s a revelation in a one-of-a-kind role for a child actor, capturing the nuances, growing humanity, and emotions of David with an attention to detail (he worked hard to make sure David turned corners the same each time, and he didn’t blink during takes) and intelligence that would- in a just world- put him up right next to “Memento’s” Guy Pearce in the Best Actor Oscar race.

Other than story, the next thing that is very Kubrickian about the film is the art direction, and kudos to production designer Rick Carter for his brilliant renditions of Baker’s artwork. The first act of “A.I.” takes place in Henry and Monica’s house, which has the distinct look of the Victorian chamber at the end of “2001” and quasi-futuristic stylings in “A Clockwork Orange,” while Spielberg’s gives the setting the otherworldly feel of Hitchcock’s “Vertigo” through the light shining through the windows and blurred camera borders. This first section of the film represents some of Spielberg’s most amazing storytelling, as a delicate bond between David and Monica forms, and is then shattered with the return of Martin; it took me some time to really decide what I thought of O’Connor’s performance as Monica, and in the end I’ve decided that O’Connor pulls off the tricky role with skill. It isn’t an emotionally shattering performance as you might expect (save for when she abandons David), and it isn’t really supposed to be; it’s clear Monica’s never really sure about her feelings for David, and that uncertainty comes through beautifully. It’s also in this act we’re introduced to Teddy, a supertoy bear whom becomes David’s closest friend and companion in his quest for humanity; he’s not a cutesy sidekick though, the voice (by Jack Angel) has the grittiness of a smoker’s cough- a bit much perhaps, but a welcome surprise.

The dark second act locales- the Flesh Fair and Rouge City- are unlike anything previously seen in either Spielberg or Kubrick, and remind one more of “Blade Runner” or “Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome,” yet with the visual energy and imagination of a music video (even Ministry- a supposed favorite group of Kubrick’s- makes a cameo appearance at the Flesh Fair). And while I found this the weakest section of the film (it seemed to drag a bit, and a voice cameo by Chris Rock was distracting), I must commend Spielberg for sticking with the supple camerawork and editing he developed in the film’s first half instead of coping out and moving to a more rapid fire style a la music videos. Apparently even Kubrick had a hard time developing this act of the film as well; I don’t know how it could have been approved on (maybe some more development of the dynamic between David and Gigolo Joe), but overall, I can’t complain about it much.

Ah, now the third act, and arguably the one going to cause the most stir among moviegoers, but also my personal favorite for all-out daring. After the trip to Rouge City, David and Joe head to the submerged ruins of Manhattan in search of the Blue Fairy; it’s here where the visual effects by Industrial Light & Magic hit their high point, as you’ll be astounded by the sight of the skyscrapers of Manhattan submerged in the sea, not to mention the sights below the surface. That’s all I’ll tell you except that the film ends with a sequence- set 2000 years in the future- that’s already one of the most discussed in recent years, mostly because while few (like myself) feel it is the only way the film could have ended, the vast majority feel “A.I.” should have ended right before the sequence. My feeling is that if it had ended where most film fans wanted it to, the film would have been incomplete, not merely ambiguous a la “2001”; it would have been like the end of “Monty Python and the Holy Grail,” where the film reaches it’s climax, only to have the filmmakers turn off the camera and start rolling the credits. The story wouldn’t have been finished, and it would be an embarrassement to both Spielberg and Kubrick’s considerable talents as storytellers. That being said, I found this final sequence to be one of the film’s most rewarding, a profound homage to “Contact” and Kubrick’s “2001” with the deep emotional power and catharsis of a dream where you’re able to connect with a loved one whom has passed on and let them know how much they meant to you. Sentimental? Well, yes, but not without merit, as the film ends with a poignant scene and voiceover by Ben Kingsley which- like the best Kubrick- opens the end up to interpretation; it’s a credit to Spielberg as a filmmaker that he probably creates his greatest homage to Kubrick with a scene that screams of one of his movies, only leaves you with the contemplative thoughts only Kubrick could manage.

All of this leads me to the following conclusion. “A.I.”- in its flawed, but exceptional way- is a thrilling reminder of the difference between following a plot (“Swordfish”) and telling a story, which it seems is a concept lost to most moviegoers nowadays. I heard one person exit the Thursday night screening I attended of “A.I.” tell the person they were with that the film had no plot. Well, no it didn’t; it was about following David’s journey in search of humanity. You want plot? Check out “Tomb Raider,” “The Mummy Returns,” or “The Fast and the Furious.” “A.I.” is the work of two master storytellers- the one who started it (Kubrick), and the one who finally told the story (Spielberg). And even though their styles couldn’t be more different, their final goals were the same- to reach an audience. Spielberg tries through emotion and sentiment; Kubrick- who’s basic philosophy about moviegoers was “See it my way, or the Hell with you.”- through unsettling stories and ideas. Either way, both directors are trying to get your attention. For two and a half hours Thursday night, both Spielberg and Kubrick succeeded…and made me want to come back again.

Click on the Title to Read Brian’s Second Look at “A.I.”

Originally Written: August 2002

Well, the dust has long settled, the critics have spoken (for the most part for the good), and audiences have chimed in- Steven Spielberg’s “A.I. Artificial Intelligence” is an overachiever artistically, but an underachiever at the box-office (at a cost of $90 million, the film only made $77 million in the US, and about $150m overseas). Not even Steven Spielberg could break the jinx that seemed to plague every potential blockbuster last summer- start off strong, and the next week take a nosedive. Like his underrated 1997 slavery drama “Amistad,” “A.I.” proved Spielberg was vulnerable. Did the film deserve such a cold shoulder from audiences? Well, if you read my review of the film back in June, you know my feeling. My point here is to shed some more light on the mysteries and questions brought up by the film, as well as added insight into my personal “gut opinion” of the film.

I wonder if Steven Spielberg knew what he was getting into when he agreed to write and direct Stanley Kubrick’s pet project of 20 years- “A.I. Artificial Intelligence”- after the great master passed away in 1999. In the weeks before and after the release of “A.I.,” there has been speculation on what “Kubrick would have done” if he had lived to film the project, reviews ranging from the most praise-worthy (Entertainment Weekly called it “Extraordinary”; US Weekly “Remarkable”) to the most venomous (Rolling Stone calling it “A fascinating wreck”; Moriarty of AICN saying it’s a “disappointment of unsuspected proportions”) and everything else in between, discussion on the sort of filmmaker Spielberg has become since the days of “Jaws” and “Close Encounters” (the argument being he’s more interested in the “rich and famous” than “real people” now), and most especially, the film’s conclusion, arguably the most controversial and discussed since Kubrick took us through that space warp in “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

After it’s release on June 29, I’ve read literally over a dozen professional print reviews, several looks at the film by the likes of “Entertainment Weekly” and “Starburst,” hundreds of “film geek” takes on the film, bought the John Williams soundtrack, as well as defended my opinion of the film (and specifically, the ending) in Talkback sessions at JoBlo’s Movie Emporium (oh, and seen the movie a few more times as well). I’ve even read the trilogy of short stories by Brian Aldiss that provided the inspiration and foundation for “A.I.”- 1969’s “Supertoys Last All Summer Long,” and “Supertoys When Winter Comes” and “Supertoys in Other Seasons,” which were written after Kubrick’s death in conjunction to the revival of interest in “A.I.”. Yes, I’ve read, seen, and listened to all of this, and will tell you what I’ve learned about “A.I. Artificial Intelligence”- the film Kubrick began, the film Spielberg completed and released this summer, and the film that opened at a little over $30 million dollars at the box-office (about equaling “Saving Private Ryan’s” debut) and was rated with a C+ by audiences through Cinemascope:

1) The Aldiss stories shed little light on the mysteries of “what was Kubrick,” “what was Spielberg,” and “what was Aldiss” in the final film (like Arthur C. Clarke’s “The Sentinal”- which begat “2001”- Aldiss’ compelling “Supertoys” trilogy is but a fruitful seed in the creation of an epic). However, a crucial difference between Aldiss’ story and Kubrick and Spielberg’s is that in Aldiss’, David is unaware of being a robot (as is Teddy); in “A.I.,” he is.

2) The foreword by Aldiss accompanying the stories- entitled, fittingly, “Attempting to Please”- and an article by Joshua Rothkopf after Kubrick’s death shed light on Kubrick’s intentions for “A.I.,” such as:

a. Kubrick’s idea to incorporate the themes of “Pinocchio”- as well as David’s search for the Blue Fairy- into the groundwork established to Aldiss.

b. Kubrick was the mind behind setting the film at a time when the polar icecaps have melted; Aldiss’ story mentions nothing of this.

c. Kubrick did initiate the idea of setting the conclusion thousands of years- with David being discovered by a more advanced for of AI- into the future, as is realized in the film. However, Kubrick’s vision of David and Monica’s reunion is- based on the Rothkopf article- indeed darker than what Spielberg has developed onscreen, so I suppose Steven is responsible for the sentimental end that so many people disliked; however, it does appear to be wrong to say that Kubrick would have ended the film with David trapped underwater, as many people would have preferred.

3) There are some absolutely freaky film geeks out there. After Moriarty published his disappointed analysis of “A.I.” on Ain’t It Cool, site owner Harry Knowles wrote in defense of Moriarty’s views, saying that he “took Spielberg into ‘A.I.’ with him,” meaning he took the fond memories of growing up of Spielberg’s classics (“Jaws,” “Raiders,” etc.), and equating his own inquiries into what Moriarty thought to talking to a friend going through a divorce, and asking “Why’d she leave you.” Now you have to admit, I’m not THIS bad when a movie disappoints me. It’s certainly not an end-of-the-world thing. But then again, I’m a late bloomer movie buff (I didn’t really get into movies until my last year or two of high school); maybe if I was a life-long movie fan I could see where Moriarty’s coming from.

4) It’s taken listening to the soundtrack album to fully appreciate the creativity of Williams’ score for the film. It still doesn’t always gel (like “2001,” it’s kind of all over the place in style), and the closing credits piece- “Where Dreams Are Born” (featuring Williams’ haunting theme for Monica, one of his best)- is perhaps too reminiscent of “Titanic,” but the music that works with the film works VERY well. Also, a personal thanks to Steven Spielberg for sparing moviegoers from having to listen to the ballad “For Always” in the movie; it’s another in the line of what I call the “Gratuitous Love Ballads” phenomenon, where every movie nowadays feels the need to have a love song at least on the soundtrack. Still, more times than not, Williams succeeds at creating a striking musical landscape for “A.I.” as the soundtrack proves.

5) Upon second viewing, the second act of the film- where David (Haley Joel Osment) hooks up with Gigolo Joe (Jude Law)- that I said dragged the first time didn’t feel as slow this time. It’s still imperfect (I’d still like to see a more gradual development of David and Joe’s friendship, and Chris Rock’s voice cameo was a distraction); perhaps it was the fact that we were sitting in our seats for 30 minutes prior to the initial viewing that made the section seem to drag. No matter- it works pretty damn well Steven…

7) …however, the transitions between sections leave much to be desired. The one between the 2nd and 3rd act of the film- which takes us 2000 years into the future- is alright (Ben Kingsley’s voiceover helps); but the move from the 1st act (which ends with Monica abandoning David) and 2nd act (beginning with our first look at Jude Law’s Gigolo Joe) is awkward. Maybe this is due to the 2nd act flaws mentioned above, and some more development time by Spielberg would have helped; maybe not. We won’t know for sure. Still, there are worse examples of storytelling out there; worse still, they made more money than “A.I.” did.

8) In the 3rd act, the beings are NOT aliens. There’s a hint as to what they are in the form of the Cybertronics symbol, but it’s so subtle many people have made the extra-terrestrial assumption. They’re actually advanced AI, machines which are descendents of David. A less subtle hint would have made the matter less confusing (even I thought they were aliens at first), but the conclusion can be come to using logical deduction apart from sci-fi cliches. Huh? Don’t ask me; I just thought it up.

9) Some critics complained about how in following David, the film abandoned a more interesting story in the Monica and Henry Swinton’s dealing with the emotional after effects of deserting David. For one thing, I disagree. Secondly, it’s not the story followed because this is a story being told to us by the futuristic mechas David is discovered by in the movie’s third act. More specifically, the mecha that speaks throughout the final third (voiced by Ben Kingsley).

10) A lot of critics compared David’s devotion to Monica to the Oedipus Complex. While I can see where they’re coming from, I disagree. There’s a slightly more logical reason- made clear in the film to those paying extra attention- for David’s love being skewered more towards Monica than father Henry. The only reason for David’s integration into the Swinton household is for Monica’s sake, not Henry’s. He has accepted his comatose son Martin may not recover; Monica hasn’t, which is why it’s only her- and not Henry- who imprints with David. If you think David just wants to get with Monica, that’s your deal; I prefer to come to a more psychologically-sound explanation.

11) OK, I’ll confess- the idea of ending the film underwater- as many would have preferred- is not as deplorable as I initially thought. It still wouldn’t work as well as the ending “A.I.” does have- which brings the story to a poignant, unforgettable conclusion, but it wouldn’t be as “incomplete” as I made it out to be originally.

12) But, here’s the main reason that ending the film underwater wouldn’t have worked. The narration- by Ben Kingsley- is actually a recounting of David’s story via the advanced A.I. David encounters in the final act. You notice how the voice of the A.I. being we hear- credited as Specialist- is the same as the narrator at the beginning and at the tail end of the underwater scene, yes? That’s not an accident. Ebert criticized the film for leaving behind “the real story” by following David and not Monica and Henry (David’s biological parents to his mechanical child); with all due respect Roger, if that had happened, Spielberg would have missed the intended story.

13) Finally, I wouldn’t trade “A.I.” for 10 “Tomb Raiders,” 5 “Planet of the Apes,” 20 “Pearl Harbors,” or even 1 “Memento.” The moviegoing experience I had with “A.I.” the first time is a rare one that sticks with you weeks after leaving the theater. It’s leaves you thinking, it leaves you enthralled, it leaves you moved, and it leaves you wanting to get back in line. For different people, this happens with different movies. Some people got it with “Fight Club”; others with “American Beauty”; others with “Jerry Maguire” or “Almost Famous”; and others with films such as “Star Wars,” “Saving Private Ryan,” or “Vertigo,” to name a few.

As for me, it’s happened a rare few times. It happened with “The Crow”; it happened with “Braveheart”; it happened with “Face/Off”; it happened with “Keeping the Faith,” “Nurse Betty,” and “Almost Famous” in 2000; it happened with “Lord of the Rings” last year, and this year, it happened with Andrei Tarkovsky’s “Andrei Rublev” when I finally saw it on DVD. These were all truly transcendent moviegoing experiences that- while I wouldn’t necessarily say changed my life- have stuck with me. These aren’t the only films of this kind- just the films I have found myself emotionally satisfied after. I remember where I saw these films for the first time, I remember when during the year and what time of day, I remember with whom, and I remember my initial reactions. I saw “The Crow” right before it left the local discount theater, and just prior to an evening band rehearsal; I left thinking about the haunting story and replaying the striking visuals in my head. When discussing “Braveheart” with my mother as we left the Thursday night advanced screening, I mentioned that I thought it would be the best film of the year at Oscar time- who knew I would be on the money? I saw “Face/Off” after a long day at the video store, and as I left the theater with tears in my eyes I kept thinking aloud- “Damn that John Woo!” (but in a good way). I saw “Keeping the Faith” just prior to leaving for Ohio last May when my grandfather was sick; I saw it six more times while up there, the last being June 1- the day he was diagnosed as being terminal- the honesty and emotion in its depiction of friendship helped me get through this most difficult period. When I first discovered Neil LaBute’s wonderful “Nurse Betty,” Renee Zellweger’s delightfully warm performance of a woman unsuspectingly on a mission to find herself was funny and touching (Zellweger worked similar acting miracles opposite Vincent D’Onofrio in the underseen “The Whole Wide World”). Watching “Almost Famous,” I saw in young William’s coming-of-age parallels in my own search for a “family” outside of my blood family. And the excitement and emotion of the story to destroy the One Ring in Peter Jackson’s first installment of “Lord of the Rings” enriched my imagination the same way people remember watching “Star Wars” for the first time.

And “A.I.?” This one dug deeper than any of those. For a film such as “A.I.,” a moviegoer is required to give their minds and patience over completely to the filmmaker; for myself, the rewards of such a “sacrifice”- if you will- were substantial. Spielberg and Kubrick’s story struck a chord with me that even fewer films (namely, “The Crow” and “The Whole Wide World”) have dared venture to; not even Kubrick’s own “2001: A Space Odyssey” went this far. Spielberg gave me a futuristic vision that- while influenced by past visions- nonetheless placed itself firmly in my imagination. He gave me a poignant, intelligent story to follow that works on multiple levels of emotions and intellect, holding true to the best entries in the genre’s creed of dealing more with ideas than effects. He even gave me a robot child whose fears, desires, and dreams mirrored my own; whose love for his mother is unconditional; and whose heart- even if it is just hundreds of feet of wire- is pure enough to engage a moviegoer in his journey, therefore proving the question put forth by a scientist at the film’s beginning- Can you make a human who loves the robot child back? In my case, the answer was yes.

(March 13, 2002 Update) The “A.I.” DVD- released March in both widescreen and pan-and-scan versions (possibly as a nod to Kubrick, possibly as a nod to those who ask “what’s with those black bars” when presented with widescreen videos and DVDs)- is Spielberg’s most satisfying release in the medium yet. Granted, there’s still no Spielberg commentary, but don’t hold your breath; Spielberg has gone on record by saying he feels commentaries can spoil the magic of filmmaking, or- better put- that they detract from the film experience. No matter- the depth of the extras (filmed during the highly-secretive shoot and production)- is a Godsend for a fan of the film. You get Haley Joel and Jude Law on acting the roles of David and Gigolo Joe; you get Spielberg and Janusz Kaminski talking about lighting and filming the film; you get glimpses of the costume and production design (including thoughts from Chris Baker, whom Kubrick initially commissioned to design the film); you get a look at the genius’ at Industrial Light & Magic at work, and hot damn, the work on the film is to-the-wall groundbreaking when you get a glimpse of it via ILM (of course, it was always pretty great); you also get a rare discussion with John Williams, discussing his striking score for the film. We also receive an exhaustive amount of storyboards and Baker’s initial design ideas, a couple of trailers, biographies on the actors and filmmakers, a “Creating A.I.” featurette on disc one, and a final featurette by Spielberg about our responsibility to A.I. (a bit too much, but hey, you only have to see it once). As for picture and sound, if you see this film on video (or Lord help you, pan-and-scan DVD), you’re missing out on an exceptional home video presentation. The visual aspect of “A.I.” is so complex that widescreen is the only way to watch this film on home video- it’s a stunning transfer- anamorphic, of course- that makes the film look more organic than “digital.” The audio for the film is a fine mix of the elements, but am I the only one who thinks the overall mix is lower than it should be? That aside, it’s a great disc, all-encompassing and slickly produced, for the simple fact that it gives fans a chance to learn about just about every aspect of filmmaking for a major blockbuster, and what is likely to be the closest we get to Spielberg revealing the tricks of his trade. (Extra points also for Spielberg, for having the guts to keep in some sobering shots- post 9/11- of the World Trade Center 2,000 years in the future. There was talk of these being digitally erased; for my part, I’m glad they kept them in.)