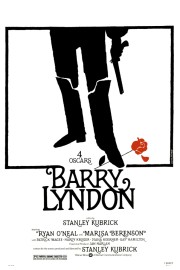

Barry Lyndon

When I mentioned this morning that I was watching “Barry Lyndon” for my “Movie a Week,” a friend pointed to something he had read that said Stanley Kubrick was “bored” making the 1975 film, that it was the work of a genius bored by filmmaking. The film “Room 237” has a similar assertion, but I feel like that is projection from a mindset that does not appreciate “Barry Lyndon,” or understand Kubrick as an artist. Would Kubrick really spend 300 days of shooting, and millions of dollars, on a film that bored him? Even when he seemed to tug in a mainstream direction with his next film, “The Shining,” you still felt like the master director had something to say in adapting the Stephen King thriller. Saying “Barry Lyndon” is the work of a bored filmmaker is not really realizing where it fits in with Kubrick’s filmmography, as a whole.

Stanley Kubrick never made another film like “Barry Lyndon,” even in his 1960 epic, “Spartacus,” but the truth is, Kubrick never really made the same movie twice, except maybe in his early, film noir days. Here, he bases his film on a novel by William Makepeace Thackeray, and it is said that the novel is the first written without a hero, and it’s not hard to see what that means. The character played by Ryan O’Neil, Redmond Barry, is the protagonist of the film, but not a hero. At first, we are sympathetic when the narrator (Michael Hordern) informs us of his father’s misfortune, dying in a duel over some horses, with only his mother (Marie Kean) to take care of him. But Redmond’s story is not a typical one of rags to riches, but rather, of an opportunist and gambler who takes chances when they meet his desires is more focused on his own wants in life than others. It was interesting that, recently, I myself have found my life being invaded by a person like Redmond Barry, so I couldn’t help but make parallels with that situation, although it is not quite the same thing.

I’ve only watched “Barry Lyndon” twice now, with about 10 years in between. The film then, as it is now, is one of Kubrick’s greatest accomplishments, and easily his greatest from a technical standpoint after “2001: A Space Odyssey.” Using natural light for the shots by his Oscar-winning photographer, John Alcott, Kubrick creates a complete, rich sense of time and place in his vision of 18th Century Europe during the Seven Years War. The film also won Oscars for costumes, art direction and music (by Leonard Rosenman, who beautifully adapts classical works from the period), and all four elements take us, vividly, into the time that Kubrick is re-creating here. Frustrated by his inability to get a film about Napoleon made, I’m sure some of that research came in handy when he set out to adapt Thackery’s novel, which came after the controversy of “A Clockwork Orange,” and landed with indifference with the audience at the time, though enough acclaim to be nominated for Best Picture, Director and Writing in addition to its victories. The film’s stature with fans has only grown over the years, and it is easy to see why, as Kubrick’s cold, dissecting style is perfect for this story of a man who cares only of himself, and is set up for self-destruction, by the end.

The film, which clocks in at just over three hours, is split into two acts. In the first act, we see Redmond as he has a youthful infatuation with his older cousin, Nora, but that will get him into trouble when she shows interest in a British Army captain, John Quin, whom her family would like to see marry. Redmond, however, is impetuous and selfish, and cannot abide by her being with anyone else. After a duel in which he appears to kill Quin, he is ordered to leave lest he be arrested, and actually finds himself joining the British Army himself, and going off to war. He later finds an opportunity to desert, when he spies upon a commanding officer with another officer, naked in a river, and he steals his uniform and credentials. He comes along the Prussian Army, and is safe from British arrest, but his lies unravel, and as punishment, he finds himself in the Prussian Army before luck finds him with further upward momentum in society. It is at this point when he finds himself in the vicinity of the Countess of Lyndon (Marisa Berenson), whom he will seduce and marry, taking her name as his own. His stepson, Ms. Lyndon’s son from her previous marriage, which ended when her husband died in war, is immediately distrustful of Barry, and sees the game he is playing with his mother. When Barry gets the Countess pregnant, however, and they have a son, Barry’s hold on the Countess makes the relationship for the family more fractured, however, eventually leading to the young Lord Bullingdon (Leon Vitali) to leave, and only come back at a moment of real emergency.

The second half of the film details the marriage of Barry and the Countess, and it’s as gripping a family drama as has been put on screen. Kubrick doesn’t go after realism or intense emotions, though, but a gradual twisting of the knife when it comes to his subjects. It’s a slow-motion car crash, with the impact heightened by the introduction of Barry’s mother into the family dynamic to remind her son that, so long as Lord Bullingdon is still in the picture, if the Countess dies, Barry and his young son, Bryan Patrick, will likely die penniless. Every moment in this drama is carefully calibrated for dramatic effect, and rather than being boring, “Barry Lyndon” is some of the most compelling storytelling Kubrick ever devised, although admittedly, that felt more true in its second half than its first. Nevertheless, the whole of “Barry Lyndon” is one of the most fascinating films Stanley Kubrick ever made. In hindsight, people are starting to catch on to that.