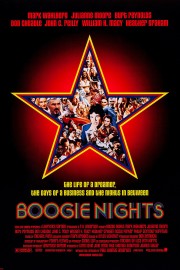

Boogie Nights

When I saw “Boogie Nights” for the first time in 1997, I hated it. A big part of why I hated it was because, a little over a week before I saw Paul Thomas Anderson’s breakthrough film in theatres, I watched Martin Scorsese’s “GoodFellas” for the first time, and, after loving Scorsese’s film unreservedly upon that first viewing, Anderson’s film was nothing more than a hollow imitator in my eyes. That was the initial impression I carried with me until finally watching it again this year, and I was very curious to see how I thought of it now.

In those early years of his career, Paul Thomas Anderson seemed overrated for his big, sprawling epics like “Boogie Nights” and “Magnolia,” but undervalued for his quiet character study “Hard Eight” and his intriguing Adam Sandler vehicle, “Punch Drunk Love.” I didn’t really feel like he put it completely together until “There Will Be Blood,” with “The Master” as a slight step back, but still a fascinating look at personal filmmaking on a large scale. (I still have not seen “Inherent Vice.”) My shift in opinion of P.T. Anderson’s work meant being intrigued by revisiting “Boogie Nights” and “Magnolia” especially, to see how they would work for me with my heightened film experience, and view on the art form, after 20 years away from them. Let us begin.

The film still maintains the rags-to-riches-to-rags again structure of “GoodFellas” in how it looks at the life of busboy-turned-adult film star Dirk Diggler (Mark Wahlberg), but with distance, I don’t feel quite as offended by that as I did initially. And I did feel offended. I was still very early in my hard-core movie watching and still learning a lot about how filmmakers operated and paid tribute to other works they admired, and hadn’t gotten into long-form critical analysis yet, so I was still rough around the edges at looking at cinema, and Anderson’s film felt like a slap in the face to Scorsese. I do not feel like that now, but nor do I feel as though it’s on the level of Scorsese’s crime masterpiece, either. For a film that deals with sex, drugs, rock n’ roll and the people who live that lifestyle without reservations, that structure makes absolute sense, and it’s a wild ride Anderson takes you on as we see Dirk leave his family, who doesn’t see him as worth anything, and go to another one with director Jack Horner (Burt Reynolds) and star Amber Waves (Julianne Moore) as the supportive parents his weren’t. That he happens to bang his surrogate mother on camera is only one part of the twisted psychology of Anderson’s motif of family coming together, being broken apart, and coming together again.

It’s easy to see in “Boogie Nights” that Anderson is a filmmaker of great ambition- kind of like Reynolds’s Horner, who sees himself as a real director rather than just a smut peddler- but he wasn’t quite ready to put it all together. At 2 1/2 hours, it moves at a steady pace, but it also feels padded with unnecessary characters, which is crazy to say given some of the people he cast in those characters. Scotty, played by Phillip Seymour Hoffman, is useless to the story, and it’s stunning to me to say that given how well Hoffman is utilized in “Magnolia,” “Punch Drunk Love” and “The Master” by Anderson. Luis Guzman is enjoyable as a character, but he has no impact on the plot at all, and could have been excised altogether; again, crazy to say about an actor Anderson would use so well later on (in “Punch Drunk Love”). Fairing better is Buck, Don Cheadle’s character, who hopes to own a stereo store of his own rather than just working for one, but it feels like filler, for the most part, although it adds context to how disregarded the porn industry is to society when he tries to get a loan for his store, but finds the stigma of having worked in porn as prohibitive. And William H. Macy’s Little Bill is an entertaining look at a sad sack who can’t deal with his wife (played by real-life porn star Nina Hartley) getting in the sack with every guy she meets- the end of his arc signals the end of this “family’s” care-free run in the ’70s and leads them into the darkness of the ’80s, where the industry turning to video will result in Horner’s hopes and dreams for his career being dashed.

Anderson, and “Boogie Nights,” fairs much better when he stays focused on his main characters, and I think one of the reasons I hated the film so much when I first saw it was that I didn’t feel the immediate connection of “liking” these people, however much they are terrible people, like I did the criminals in “GoodFellas.” Honestly, I still could do without seeing the stories of Dirk Diggler, Amber Waves and Jack Horner and characters on the sides of their lives like Rollergirl (Heather Graham) and John C. Reilly’s Reed Rothchild. While it’s not a requirement of films to make characters we “like,” we should at least become engaged with them as individuals, and even now, I don’t really feel that engagement in these characters. Dirk is, honestly, kind of a dick, and Wahlberg didn’t quite have the weight as an actor to make me care one iota about the dilemmas Dirk finds himself in after his falling out with Horner. (That said, him badly recording Stan Bush’s “The Touch” from the animated “Transformers” movie for a demo is probably my favorite moment in the film.) Horner is a stern father figure, and Reynolds is perfect in the role, but I don’t have much empathy with him late in the film when a horny douche calls him a bad filmmaker, and he starts kicking the shit out of him. And I’ve always had a tough time with Moore’s Amber Waves and her arc. She is a delinquent mother to her son, Andrew, and while we are suppose to empathize with her when her ex-husband lays down the reasons why she shouldn’t see him, I just don’t have that empathy or engagement with her plight, especially since, not a few scenes before, we see her doing drugs with Rollergirl as they talk about getting their lives together. It has nothing to do with Moore’s performance- I just am not on board with the way Anderson writes these characters, and the result makes for a frustrating experience from a filmmaker I now have more admiration for, but still can’t quite endorse this acclaimed early effort from.