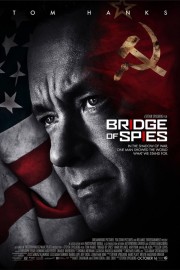

Bridge of Spies

One of the most fascinating aspects of Steven Spielberg’s career in the past 22 years has been how he has explored the notion of the “American Dream” or the American way of life through the context of how we treat people, or rather, how our government treats people. This includes how Homeland Security deals with people coming in to the country (“The Terminal”); how life has suddenly been upended by a surprise attack on American soil (“War of the Worlds”); how our government agencies have responded to terrorism, both out of the country (“Munich”) and within our borders (“Minority Report”); and how the legal justice system has entered muddy waters when it comes to civil rights in the face of abhorrent racism (“Amistad” and “Lincoln”). In his latest film, “Bridge of Spies,” Spielberg continues this trend in his work, by taking a key moment of diplomacy during the Cold War, and using it to comment on not just how we engage with our geopolitical rivals, but also how we treat those we view as “the enemy” if we capture them. By choosing to tell the story of Jim Donovan, a Brooklyn lawyer thrown to the wolves of public opinion when he’s asked to represent a Russian spy, he is showcasing the golden rule of treat others how you would wish to be treated. It’s a fascinating story, albeit a minor film compared to some of Spielberg’s work in the past two decades; “Lincoln,” “Munich” and “Saving Private Ryan,” this is not.

The story Spielberg chose to tell in “Bridge of Spies” would be enough to make it a must-see from the great director, with him collaborating with Tom Hanks for the fourth time simply being a cherry on top, but there are two intriguing behind-the-camera collaborations that really helped pique my interest. The first is that the screenplay is co-written by Joel and Ethan Coen, marking the second major writing collaboration they’ve made in two years where they didn’t direct the film (the first was with Angelina Jolie on “Unbroken,” also about a prisoner during war time). They share credit on the script with Matt Charman (whom I’m guessing was the original writer), and it’s a wild time watching the film unfold with a bit of that Coen Brothers quirk every once in a while. Another great aspect of Spielberg’s career of late has been the variety of screenwriters he has worked with of late, which includes not just the Coens but Tony Kushner (“Lincoln,” “Munich”), Scott Frank (who did a key punch-up on “Minority Report”), Richard Curtis (who helped adapt “War Horse”) and Edgar Wright and Joe Cornish (who helped shape the shooting script on his 2011 animated film, “The Adventures of Tintin”). Seeing him branch out and work with interesting writers (many of whom are accomplished filmmakers in their own right) has made even the films of his that have been merely “good” smart and sometimes unusual entertainments. The second collaboration on “Bridge of Spies” I referred to earlier was the composer on the film. Earlier this year, health issues prevented John Williams from continuing his streak as Spielberg’s typical composer, making “Bridge of Spies” the first Spielberg film in 30 years without a score by the 5-time Oscar winner (the last one was “The Color Purple,” which was scored by Quincy Jones), although he will be back for Spielberg’s next film, “The BFG.” Filling in is another venerated film composer, Thomas Newman, and his distinct sound fits in nicely with the rhythms and feelings Spielberg needs to capture for this tale of espionage and intrigue. When, God forbid, Williams finally goes to that orchestral hall in the sky, I hope we see more collaborations between Spielberg and Newman, because they are very much in sync in this movie.

The film begins with the FBI tailing an ordinary-looking individual through Brooklyn. He stops and paints the scene by a bridge, and the first time we see him, he is doing a self-portrait. The man’s name is Rudolph Abel (Mark Rylance), and according to the US government, he is a Russian spy, although we have seen him seemingly retrieve something in the park by the bridge, which he promptly gets rid of when the hotel room he is living in is searched. He is taken into custody, and in the court of public opinion, already guilty and awaiting the death penalty. However, we have a little thing called “Due Process” that allows people the right to a fair trial, whether they are citizens or not. How does that work when everyone from the media to the presiding judge already assumes Abel’s guilt? When Jim Donovan (Tom Hanks), an Insurance lawyer who is assigned the case as Abel’s defense attorney by the American Bar Association, decides to put his weight behind the case, he finds out that justice is, indeed, blind when it comes to the security of the United States during the Cold War. He manages to keep Abel from getting the death penalty thanks to some simple political logic, and it’s a good thing, too, as his reasonable argument (that Abel may prove valuable if one of our spies is taken hostage by the USSR) gets put to the test when pilot Francis Gary Powers (Austin Stowell) is shot down while on a recon mission, and is taken into Russian custody. A trade is proposed, with negotiations to take place in East Berlin as the Wall was going up. Donovan is recruited for the task, as he is seen as a civilian, and as Abel’s lawyer, he knows the truth as to whether Abel has talked to the US government in exchange for leniency. However, when an American student named Pryor (Will Rogers) studying communist economics in East Berlin is taken captive by the East German government, what started as a simple trade becomes a complicated geopolitical chess match that could, if not played properly, lead to nuclear holocaust.

Even though I will always find time to watch the likes of “Jaws,” “E.T.,” “Raiders of the Lost Ark” and “Jurassic Park,” the past two decades of Steven Spielberg’s career have been arguably the most exciting we’ve seen out of any filmmaker who’s worked as long as he has. With “Schindler’s List,” Spielberg found a spiritual purpose to go with his populist style, and it’s been thrilling to see him challenge himself with films as varied as “A.I. Artificial Intelligence” (from an idea by Stanley Kubrick), “Saving Private Ryan” and “Munich” and “The Adventures of Tintin.” “Bridge of Spies” isn’t quite as daring as those films are, but it’s very much of a piece with some of his finest work during this period in the way that it looks at American values through complicated moral arcs. Some critics have likened it to “To Kill a Mockingbird,” and the comparison is an apt one, although Donovan’s story is not so black-and-white. Or is it? Watching without bias, it’s easy to see the rationale through which he came to the conclusion that Abel should live, and his emotional arc with his client is one that is laid out simply and carefully, allowing the payoff near the end to resonate as strongly as any Spielberg has put on-screen. His cast is uniformly strong, ringing the humor and humanity out of the script, but the two actors who really excel are Hanks and Rylance. Hanks is basically Gregory Peck’s Atticus Finch in “To Kill a Mockingbird,” forced to find a solution to an almost impossible problem, but the actor delivers the same nuance and intelligence he brings to every character. The standout, however, is Rylance, who paints Abel as someone who understands the situation he is in, but finds calm is the best way to handle himself. (As he always responds when Donovan asks him if he’s anxious or worried, “Would it help?”) Whether he really is a spy or not, we understand why, when confronted with this man, Donovan goes to great lengths to protect him, and keep him alive. Theirs is one of the most compelling narratives of the year, and it is great to see Spielberg really dig in, and get to the heart of the matter without forcing you there the way he tends to do. It may not be a masterpiece from the filmmaker, but his success with that part of the story makes it a rarified entry in one of the most extraordinary careers in movie history. It will stay with you.