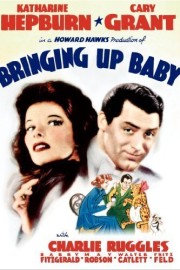

Bringing Up Baby

Howard Hawks’s “Bringing Up Baby” has three hours worth of dialogue compressed into 102 minutes, and that’s why it’s such a wonderful watch. The screwball romantic comedy has long been out of fashion in Hollywood, and I think a big part of it is that there are not really writers and actors who can make it work on screen, anymore. This type of comedic storytelling is more suited for television now, and filmmakers are more enamored with improvisation than rapid fire screenplays. For that reason alone, films like “Bringing Up Baby” are worth rewatching, and discovering if you’re coming to it for the first time.

Hawks is a filmmaker who didn’t stay within the confines of a single genre, whether it was crime dramas like “The Big Sleep” or “Scarface,” westerns, or comedies- he came from a time in Hollywood where directors didn’t particularly specialize in genres like they do now. They gravitated towards stories, and worked within particular archetypes. But you could still argue that, in the choices of stories they made, filmmakers such as Hawks found a way to put a particular personal stamp on their work, which is an idea I look at below.

As for “Bringing Up Baby” specifically, Hawks is the ringmaster controlling the manic energy and action surrounding David (Cary Grant), a museum curator about to be married, while also trying to get a million dollar donation from a wealthy old woman, and Susan (Katherine Hepburn), an eccentric you socialite he keeps running into, and whom keeps reeking havoc in his life. The film is based on a story by Hagar Wilde, who co-wrote the script with Dudley Nichols, and it’s a model of complex storytelling that moves like clockwork from one situation to another while having a logical progression to its conclusion. Not just because of the fact that Grant and Hepburn were giant stars do we understand how, and why, David and Susan will inevitably fall in love, and end up together, in the end. As David tries to deal with the whirlwind Susan puts him in the center of as she plays the wrong golf ball, drives the wrong car away, needs help with her leopard, and her dog takes David’s dinosaur bone and buries it during a chaotic two days, we witness the steady progression of changing moods and emotions that will lead to their coupling in the end.

“Bringing Up Baby” is just a great movie comedy. There really isn’t anything more to be said about it beyond that. Grant and Hepburn are a wonderful pairing, and the way Hawks and the screenwriters keep things moving at a rapid-fire pace is a joy from beginning to end. Any movie that can find a way to naturally put a leopard following Cary Grant and a dog digging up a pair of shoes (one per hole) while the characters are trying to find a newly-buried dinosaur bone while Katherine Hepburn plays a role that feels equally frustrating, but also instantly lovable, is hard to dislike, if not impossible. It’s a classic for a reason.

I wrote the following for a class on Film & TV I took at Berklee Online in 2014:

I have decided to focus on the film, and Hawks, from the perspective of the “auteur theory,” because while a great admirer of the director (“The Big Sleep” is one of my all-time favorite films), I never really looked at him as an auteur in the same way we think of directors like Hitchcock or John Ford. But Wollen’s essay certainly makes a case for it.

In regards to “Bringing Up Baby” in particular, two ideas Wollen writes about stood out as being important to understanding Hawks’s place as a true “auteur.” The first, and most obvious one, is when Wollen brought up Hawks’s definition of “crazy” as “difference, a sense if apartness from the ordinary, everyday, social world.” (p. 273) That idea of “craziness” is all over “Bringing Up Baby,” especially in the character of Susan, played by Katherine Hepburn. Susan sets the tone for the entire film from the first moment we see her on the golf course as she plays David’s ball, which he shot onto the fairway she’s on. Even though David (Cary Grant’s character) speaks at a rapid-fire pace from the get go (a common trait in the screwball comedy), in the first scenes, he comes across as a regular human being, getting ready to settle down into marriage, and excited about the possibilities in his professional life. Once Susan comes into life, however, there’s no going back to the ordinary social world, and he’s immediately drawn into a world where Susan rings David after their first, awkward meetings together and casually mentions that she has a leopard in her apartment. Communication becomes more difficult, although a lot is communicated between the characters in short periods of time; that doesn’t mean people are really listening, or even communicating in a straightforward manner. It’s almost like an alternate reality from the regular world Hawks establishes at the start of the film. As I was thinking about this film in relation to other films of Hawks’s I’ve seen, the more I feel like Hawks did a similar thing later in “The Big Sleep,” where the film starts out in a very standard fashion, in a very familiar movie world, but once Phillip Marlowe enters the Rutledge house (where he meets Lauren Bacall’s character), Hawks moves us into an alternate world where behavior doesn’t really match what it would be like in the real world, or at least in the movie world we see at the beginning of the film. In that respect, both “Bringing Up Baby” and “The Big Sleep” have a huge structural aspect in common that ties the two, otherwise different, movies in common, allowing us to easily place Hawks in line with the auteur theory.

The other part of Wollen’s essay that stood out to me was on page 275, when he was discussing how sexual role reversal played a big part in Hawks’s comedies, and indeed, that is a huge aspect of “Bringing Up Baby.” Although Grant’s David starts out as a traditional leading man, once Susan comes into his life, he becomes nothing more than a pawn for her to move around as she likes. She may seem like a flighty, easily-distracted woman when we see her on the golf course, but we come to realize rather quickly she’s incredibly smart, and definitely the stronger personality between the two; after all, how else would she be able to get David to take a trip with her all the way to Connecticut, and completely abandon his everyday life, if she were just an impulsive young woman? It’s obvious by the time David drops everything (except his long-awaited dinosaur bone) to come to her help when she’s played like the leopard is attacking her that David’s attraction to Susan is a romantic one, even if it’s not spoken until the very end of the film. Susan has had THAT type of impact on him, and they’ve just had a couple of interactions together.

I’ve only seen a handful of Howard Hawks’s films, but looking deeper at “Bringing Up Baby” (and just seeing it, in general) has me excited to look further into his films, and find commonalities that further justify Wollen’s identification of him as a true auteur.