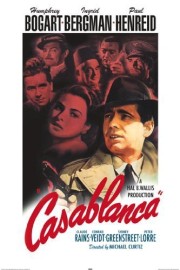

Casablanca

It’s terrifying to consider that, in modern day Hollywood, the ending to one of the greatest of all movie love stories wouldn’t make it past test screenings, whose audiences surely would have insisted that Rick and Ilsa ended up together in Michael Curtiz’s “Casablanca.” Maybe that’s me being cynical about modern audiences, but at a time where it seems like every aspect of a film focus grouped for maximum popularity, one must at least contemplate that in a parallel universe somewhere, a version of “Casablanca” exists where Victor Laszlo remains in Casablanca, to be headed back to the German concentration camps, while Rick and Ilsa get away on the last plane out of French Morocco to America to live happily ever after. There’s a part of me that would want that, as well, but it would be a wrong ending for this film. “Casablanca” turns on the longing for love lost, not love found and maintained. Ilsa felt it for Victor, which is why she couldn’t meet Rick at the train station in Paris, and Rick is defined by it when, “of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine,” and those feelings come racing back. Rick may be in love with Ilsa, but he knows that Ilsa loves Victor, and Victor needs Ilsa. Besides, deep down, Rick knows that he’s better on his own anyway, and he will be fine.

How is it that one of the best movies in film history started off as simply another film coming down the Warner Bros. assembly line? Greatness does not come from intent, but execution, and “Casablanca” is a great film because it was executed with intelligence and a lack of self-importance. Curtiz made two other features in 1942, including another beloved film in “Yankee Doodle Dandy,” and yet, this is the one he is most remembered for, and won the Oscar for Best Director for. His direction was more workmanlike than “great,” but what was great about it was the way he took the script by Julius and Philip Epstein and Howard Koch, and a cast that includes some of the biggest names in movie history, and made something that holds up effortlessly after years of being rewatched by moviegoers. What made the script so special, though? It was based on a play that has less notoriety now than the film it was adapted into, and lines of dialogue were being rewritten and sent to the set each day. Hell, they didn’t even have an ending until the day they shot the ending, according to filmmaking lore. Yet, other films show the seams of such writing nightmares- how is “Casablanca” an exception? This is more of a case of everyone being on the same page, day in and day out, regardless of what that last page ended up saying. The actors may have been huge stars, but they trusted the writers and director to know what was best for their movie, rather than pull a “star ego” out and get the ending they wished. Victor and Ilsa getting on that plane together was what was best for the movie, and everyone involved with it knew it. That is how “Casablanca” became great- the film was what was important, not stroking the ego of one person or another.

Here I am, though, discussing the ending of a movie in very explicit detail without using the words **Spoiler Alert** in an age where so much as a hint of something in a movie’s story can lead fans into a rage. I think a big part of that comes from the fact that it’s difficult to imagine someone being alive who has not only not heard of “Casablanca,” but doesn’t know the plot in detail whether they’ve seen the movie or not. (It is 74 years old, after all.) Like a beloved song or book, “Casablanca” is so ubiquitous in movie history that people who have never seen anything past the year they were born have probably at least heard about it, or seen an homage to it in another movie. Few movies have more memorable lines of dialogue than it, or a more memorable cast of characters. Nowadays, ensemble cast of this stature are rarefied air, as recent decades have brought more of a star-driven system than even the old studio system that resulted in “Casablanca” can claim to. Today, a cast with so many major stars in it is more reserved for “prestige” films than run-of-the-mill productions, but in the ’40s, such a thing was quite typical of the time, as Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Reins, Conrad Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet and Peter Lorre were not really freelancers but likely on salary at the studio, so that “Casablanca” would have very much been just “another job” in their contract with Warner Bros. for them. But such happenings is the stuff dreams are made of, to quote another Bogart classic, and it’s the type of situation that makes someone who laments how predictable and cookie cutter cinema has gotten from the major studios wish the industry could return to the old days. With so much emphasis on the globalization of cinema and the inflation of salaries, though, a film with the pedigree of “Casablanca” would be too much to bankroll, and expect to make a profit. That is a sad situation, indeed, but it makes one profoundly grateful for the happenstance that led to the making of a classic such as this.

That I still haven’t really discussed any part of the story apart from the ending is probably inevitable due to it’s familiarity. The film hinges on the murder of two German couriers who are carrying letters of transit needed to leave French Morocco during WWII; the letters are the film’s “McGuffin,” but the thing propelling the story is the love triangle between Bogart’s Rick, Bergman’s Ilsa, and Henreid’s Laszlo, and the suspense of who will use the letters to leave. There isn’t a false note hit by this film, which isn’t to say that the film is realistic, but simply that in the context of the film, there isn’t a moment that feels unbelievable. We believe Rick’s cynical outlook after the heartbreak of Paris, Ilsa’s complicated emotional state with her past catching up to her, and Laszlo’s ability to inspire patriotism, and why that is so dangerous to Veidt’s Major Strasser. We love the camaraderie our main characters have with Dooley Wilson’s pianist Sam and Reins’s Captain Renault, and the sinister side of Casablanca we are exposed to by way of Greenstreet and Lorre’s morally dubious characters. We enjoy the musical interludes led by Sam like “Knock on Wood” or the iconic “As Time Goes By,” the comedy of a pickpocket doing his work, and the steady stream of memorable dialogue. Rick and Ilsa’s problems may not amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world, but watching them unfold is an unforgettable experience. They’ll always have Paris. We’ll always have “Casablanca.”