Chimes at Midnight

Like most people, I’ve only known “Chimes at Midnight” by reputation rather than actually having seen it. That is because Orson Welles’s film, for much of its 50 years after having been made, had been entangled in legal troubles that kept it out of American distribution. Alone, that would make it essential viewing for me, having come to appreciate much in Welles’s career, even later works like “The Trial” or even his incomplete “Don Quixote,” but “Chimes at Midnight” had a reputation as having been inspiration for one of my very favorite films, Mel Gibson’s “Braveheart,” in how Gibson staged the epic battle scenes in his film. Watching Welles’s staging of the Battle of Shrewsbury, Gibson practically did a shot-for-shot recreation, and honestly, I get it- Welles got this right, and that he did so with minimal budget and resources makes it all the more impressive his thrilling direction of the battle in this film.

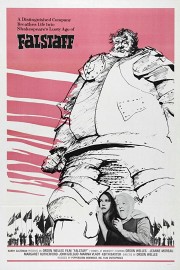

I’m going to be honest- there are times when it feels like William Shakespeare is a foreign language to me, and when it started, “Chimes at Midnight”- in which Welles plays Shakespeare’s Falstaff, from Henry IV– was definitely that way for me. It wasn’t easy for me to follow the film and story, and I worried that my lack of previous experience with the primary text was a hindrance to my ability to appreciate the film. It doesn’t help that Welles’s iconic voice- gruff and grizzled as he entered the last two decades of his life- and Shakespeare’s words didn’t feel like a match made in heaven, either, and, despite being recently restored for the Criterion Collection, the soundtrack wasn’t as crisp as you’d hope. At times like this, however, trust is required by the filmmaker, and the conviction of Welles’s direction, and faith in his adaptation of Shakespeare, wins out, and all the essential beats of the story play out in the still capable hands of Welles.

The film begins with Falstaff and a companion traveling through the snow, and they come upon a fire at the Boar’s Head Tavern. They begin to reminisce, and the film goes to the opening credits, after which a narrator explains the political situation we are thrust into: King Henry IV has succeeded Richard II, whom he has killed. Richard’s true heir is a prisoner in Wales, and the heir’s cousins demand that Henry rescue him. Henry denies, and the cousins- Northumberland, Worcester and Northumberland’s son, Hotspur- begin to plot against Henry in an attempt to overthrow him. At this point, however, our interest in diverted away from that political situation and towards Henry’s son, Prince Hal, his heir, and far removed from what Henry would have him be, which is his next-in-line. Instead, when we meet Prince Hal, he is a thief and companion to the drunken knight, Falstaff, a once-great man of the court, but now, an obese, oft-drunk shadow of his self who lies and steals to enjoy a life of pleasure at the Boar’s Head, whose proprietor he owes much money.

The central dilemma of the film is a fascinating one- a son caught in between two very different father figures and role models- and I’m curious how much the perspective of this film diverges from Shakespeare’s original plays (while much of the material is lifted from the Henry IV plays, it is said that Richard II, Henry V and some dialogue from The Merry Wives of Windsor are a part of Welles’s story here), because it’s hard to imagine Shakespeare gave quite the weight to Falstaff and Prince Hal’s story that Welles does here, but that’s what can be exciting about one great writer and storyteller taking on another- they will adapt what interests them, and enlighten parts of the original work that the author didn’t consider. By putting Falstaff front-and-center, Welles is telling a more personal story than a straight adaptation of Shakespeare would allow, and his Falstaff is bawdy and funny in addition to tragic and mournful- I did not expect the level of humor Welles invests in both his characterization of Falstaff but in the film as a whole. I have a feeling the direction of the battle scenes is not the only thing that inspired Mel Gibson when he made “Braveheart,” and it shows.

I remember studying some Shakespeare in high school, and, of course, I’ve seen some films based on his plays, but on the whole, I feel relatively unfamiliar with his writing. “Chimes at Midnight” makes me want to rectify that, which is probably the highest compliment I can give Welles’s film. He has made Shakespeare a living thing for me in his entertaining and poignant film, which I am grateful for finally being able to watch. I do not know if I would put it with his greatest films, but it’s definitely one every fan of his should watch, if only to celebrate its welcome availability, at last.