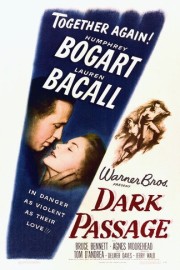

Dark Passage

I’d heard about “Dark Passage” from a film-loving friend at my work about a decade ago when I was professing my love for film noirs such as “The Maltese Falcon” and “The Big Sleep,” but I only now have gotten to watching it, and I’m grateful I did. Not only is it another winning combination of Humphrey Bogart and his love, Lauren Bacall, but it also starts off as one of the most distinctive crime thrillers of all-time from a cinematic standpoint. How the director, Delmer Daves, was able to convince Bogart to be heard, but not seen, for much of the first hour of “Dark Passage” speaks a lot to how smart he was as a filmmaker, and how lacking in movie star vanity Bogart was.

“Dark Passage” is based on the novel by David Goodis, and one of the things that is striking while watching films from the ’40s and ’50s, in particular, is how many genre pictures were not original scripts, but based on existing properties. “Dark Passage,” like a lot of film noir and crime pictures of that time, doesn’t feel like how modern audiences view literary adaptations, but that’s because this coincided with the development of a genre in film noir. That name would not be coined until a decade later by the critics/filmmakers of the French New Wave, but it is a distinctly American film genre, with heroes who didn’t act heroically, and love interests who were hard to get, and not exactly innocent bystanders in the story. In “Dark Passage,” Delmer Daves brings together a compelling hook (Bogart and Bacall as the leads), and a striking visual trick, to tell the story of Vincent Parry (Bogart), a convicted murderer who escapes from San Quentin penitentiary, and is picked up by two motorists- the first, a man (Clifton Young) who needs to be dealt with after he puts the pieces together quickly, the second, a woman (Bacall’s Irene Jansen) who knows exactly who he is, and wants to help him. Her reason? She thinks he is innocent. These two will play critical roles in the story to tell, as well as a friend of Irene’s (Madge, played by Agnes Moorehead) who knows something about Vincent, and gets might suspicious when she comes to visit Irene one time.

Dark lighting and unusual angles, which were prevalent in German Expressionism, are key characteristics of film noir, but Daves also uses a bit of trickery in the form of point-of-view cinematography (shot by Sidney Hickox) for a particular purpose. You see, Vincent, at the time of his escape, does not look like Humphrey Bogart- it’s only after a late night trip to a plastic surgeon that he looks like the star of “Casablanca” and “The Maltese Falcon.” However, rather than cast someone else in the role pre-surgery, Daves simply has the camera provide Vincent’s eyes, putting us in his experience for much of the first hour of the film. It may have been a convenient way to make the movie, but it’s also an inspired touch that infuses the genre, and story, with fresh life and energy. We are put in Vincent’s place as he escapes, and makes his way through San Francisco, and Daves and his composer, Franz Waxman, put a compelling emotional hold on us by doing so, giving an immediacy and vitality, in particular, to the scenes of Bogart and Bacall, during which we are still not quite sure about Bacall’s Irene or her motives. Film noir is not particularly sympathetic towards its characters, but because of the way Daves tells the first part of the story, we feel sympathy towards Vincent, and hope to see him get through his predicament. It’s a spoiler to tell you that he does, but it’s a necessary one to point out that this ending feels forced and not really plausible for the story it has told. I guess that’s where the star power of one of Hollywood’s most legendary couples came in to play. It doesn’t hinder the overall impact of what came before it, and from an emotional standpoint, is a piece with the rest of Daves’s film. It just is unusual to see such optimism in a story that goes to some dark, ambiguous places of the human condition.