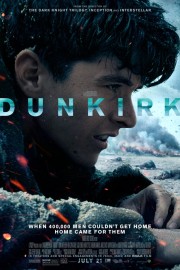

Dunkirk

“Dunkirk” is, handily, Christopher Nolan’s shortest film since his 2001 breakthrough, “Memento,” although it’s probably his most personal film to date. This feels like the sort of film a director will only get to make after banking an awful lot of cinematic capital over the years, and the director of the “Dark Knight” trilogy, “Inception” and “Interstellar” has certainly done that. Those expecting “Saving Private Ryan” will likely be disappointed- the film is a largely bloodless affair, and much more of a meditation on war, and the different fronts it comes at soldiers, than a thrilling battle film. It reminded me a lot of Terrence Malick’s “The Thin Red Line,” although not quite so pretentious. Nolan demands that you pay attention to faces, and motives, without spelling anything out for you. It is his most tightly-composed film since 2006’s “The Prestige,” and it shares many traits with that film in how it approaches its story.

First, I must say a word about Hans Zimmer, the film’s composer. This is now the sixth collaboration he has had with Nolan, and it is obvious that he is thriving under the versatility Nolan demands of him from film to film. Even with his work on the “Dark Knight” trilogy, his scores for Nolan have some nuanced variety that could get lost with a more casual moviegoer, which is understandable considering Nolan encourages Zimmer to go for the “big” gesture, more often than not. Zimmer has done some of his very best work of late with Nolan, but the soundscapes for Nolan’s last two films, “Interstellar” and “Dunkirk,” have been controversial for Nolan’s choices when it comes to the sound mixes. By giving deference to the scores and sound effects over dialogue, it can result in a confusing, disheartening viewing experience. In “Dunkirk,” the war setting makes it understandable, but the almost-constant score by Zimmer (who also scored “The Thin Red Line,” which is one of his best works), while imaginative and fitting for the film, is over-insistent and doesn’t add to the emotional impact of the film. Contrast that to John Williams’s comparatively-sparse score for “Saving Private Ryan,” which didn’t even bother with the battle scenes, but is one of the master’s greatest pieces of composition in a legendary career. I feel like I finally should tell Nolan and Zimmer that less is more, because in this case, it likely would have been.

The film Nolan has come up with tells the story of the Dunkirk evacuation, which happened in 1940 during WWII. British and French forces had been backed up to the beaches of Dunkirk, with no way to escape. We see what happened next from three fronts: The Mole (the land), the Sea, and the Air. Our first image of the film is a British soldier, Tommy (Fionn Whitehead), running with members of his company, trying to get to friendly territory in the town of Dunkirk, as they are besieged by gunfire from unseen German forces. Tommy is the only one who makes it, and we see as he tries to get off the beach as quickly as possible and get home. The beach is filled with hundreds and thousands of soldiers trying for the same thing- unfortunately, Winston Churchill and the British leaders have deemed it too dangerous to send in a fleet to rescue the soldiers, meaning a waiting game they may not survive. Meanwhile, two RAF pilots (Tom Hardy and Jack Lowden) roam the air, keeping an eye on their fuel gauges as they try to take down German pilots looking to blow up what vessels are rescuing people from Dunkirk. Those ships will later including civilian boats, commandeered by the British Navy, to try and get people out; one such boat is piloted by a father (Mark Rylance), whose son (Tom Glynn-Carney) and a friend (Barry Keoghan) are helping get people out of the water, including a soldier (Cillian Murphy) whom they find atop a sunken ship bow, and who’s shell shocked when he is told where they are going. The film is a race against the clock as survival is the primary objective.

Discussing the film with a friend of mine today at work, it was easier for me to solidify what, exactly, it is about the film that keeps me from considering it as, possibly, Nolan’s best film yet. From a technical standpoint, the film is, honestly, amazing; the editing by Lee Smith shows how clear and clean Nolan’s storytelling instincts have become over the years, while cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema (“Interstellar”) does amazing work at bringing us to the common person’s perspective, and creating a claustrophobic feeling as the walls have closed in around the British and French soldiers at Dunkirk. I have already discussed the sound mix and Zimmer’s score, and while I have already discussed my issues with both, I would be lying if I didn’t admit that they aid Nolan in his final effect completely. What keeps this film from reaching the heights of his finest work, however, was the lack of engagement I had with any of the characters that would have brought it down to a personal level for me. The film had my attention on a superficial level, but not an emotional level, and that is crucial for a film that is going to fly in the face of the typical war movie cliches. The performances are all strong, but none of them (except maybe Rylance’s) stood out as an anchor for the film to take me to another level as a moviewatcher. I understand what Nolan is wanting to achieve with the film (namely, a documentarian’s objectivity to his subject), but a story of survival requires an emotional component that this film lacks. In an odd way, it makes “Dunkirk” almost as hopeless a film to watch as the event must have been for the soldiers who went through it, and that is one of the most painful realities the film illuminates.