Fahrenheit 451

It feels weird to say that 1966’s “Fahrenheit 451” was my first Francois Truffaut film, because there really isn’t much that distinguishes it, strictly speaking, as a Truffaut film. It wasn’t until the 2000s, and really, very recently, that my exploration of Truffaut’s filmography began properly- his adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s famous sci-fi novel came in front of my eyes because, at the time, Mel Gibson was looking to adapt it. Now, HBO has an adaptation of the book coming next week, so it is fitting that I revisit Truffaut’s film, and it was definitely interesting to revisit it in light of being more familiar with Truffaut’s work.

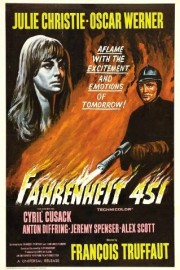

This was Truffaut’s only English-language film, and- I believe- his only foray into sci-fi, save for his supporting role in Steven Spielberg’s “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.” Bradbury’s story is a famous one, as it takes place in a dystopian future where free thought is discouraged, and firemen now have the job of not preventing fires, but starting them, as they act as policemen enforcing laws that ban printed materials and books, finding them and burning them. This is the life of Montag, a fireman played by Oskar Werner who has a content life with his wife (Linda, played by Julie Christie), who sits around watching television all day, and is one of the best fireman at his firehouse, 451. One day, he meets a woman on a train (Clarisse, also played by Christie) who challenges him on his job, and pushes him on the very notion of what he is doing. He then begins to read books he is meant to burn, and he finds himself upending his life as he knows it.

Watching the film, it pains me that the resources were not available to Truffaut to make this film as visually rich as it should be. Shooting in color for the first time in his career, he and his cinematographer, Nicolas Roeg, make sumptuous use of the reds of the fire truck and firehouse, and the reds in the fires burned on camera, in this film, with a scene where the firemen have to burn an entire house, which is filled with books, and the owner sacrifices herself with the knowledge she kept hidden. Unfortunately, it’s impossible for Truffaut not to make this film look like it was shot in 1960s suburbia in London, and it make it difficult to really feel like he was taking me somewhere as a viewer. Along with the cinematography by Roeg, much of the heavy lifting has to be done by the score by Bernard Herrmann, which is a lovely piece of evocative, atmospheric writing by the great collaborator of Truffaut’s hero, Alfred Hitchcock. The rest of the aforementioned “heavy lifting” has to be done by Werner and Christie; Werner is good for what he is asked to do, but he doesn’t really have much charisma, although Christie is quite lovely, and interesting, in her duel role.

Even more than being Truffaut’s only English-language film, the film feels like an anomaly in Truffaut’s career because it doesn’t often feel like it has much of a personal touch coming from the director, who (arguably) wore his heart on his sleeve more than any other director to come out of the French New Wave. I think he feels strongly about the notion of government censorship and the suppression of free thinking, and I think he finds a way to make some satirical points against television, and especially, TV news, which can be used as a tool of government propaganda. Ultimately, however, I think he comes at this material from a distance, much like Montag does the nature of his work at the beginning of the film. I don’t know if he’s exhibited the same evolution as his protagonist has by the end of the film, though, despite the ending in the woods being kind of haunting and beautiful.