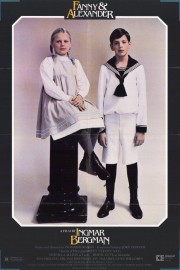

Fanny and Alexander

Ingmar Bergman is one of the few filmmakers who could make a three-hour film about family, and all of the dynamics at play in one such as the Ekdahl’s, and make it wholly engrossing from beginning to end. That’s not to say that I will be watching the five-hour version of his 1982 film, “Fanny and Alexander,” that he made for television anytime soon, but I cannot help but be grateful to finally have seen this film, because it is as good as any the great director ever made.

The film takes place in the early 20th century, and when we meet the Ekdahl family, it is on Christmas. They are a large family, with a matriarch, Helena, preparing for her annual family feast. They own a local theatre where they are having a production of the Nativity for the holidays. Helena has three sons- Gustav Adolf, whom is a philadnerer, but whose wife, Alma, loves him anyway; Carl is a failed professor who, along with his wife, are in debt; and Oscar, who runs the local theatre and is married to Emilie, and has two children, Fanny and Alexander. We see the dynamics within the family which will play out over the next three hours in this opening, and one of the things that is so striking is how close and caring the family largely is to one another. Considering the destructive families in “Cries and Whispers” and “Scenes From a Marriage,” this feels like a very unusual shift for Bergman, but one that he shows us masterfully, and with the affection of a man remembering his childhood. For the first hour it’s kind of remarkable how little of the film focuses on Fanny and Alexander, but Bergman rewards it with beautiful material such as that involving Gustav (Jarl Kulle), his tryst with Maj (one of the maids, played by Pernilla August), and his returning to Alma’s room afterwards; everyone involved knows what is going on, and the help will not say it, but Alma (Mona Malm) is comfortable with herself, and loves Gustav dearly, making it alright. The way that particular story thread plays out later in the film is wonderful in how we see life at its most compassionate, and family at their most understanding. Given the place we are at in the narrative, we need that light more than ever.

After the introduction of the family, it begins to focus in on Oscar (Allan Edwall), Emilie (Ewa Froling), Fanny (Pernilla Allwin) and Alexander (Bertil Guve). Not long after the holidays, Oscar dies, and the pain with which we see the reactions by Emilie, Helena (Gunn Wållgren) and the kids grieve him is as palpable and potent as anything Bergman had ever put on film. In her grief, Emilie has turned to Bishop Edvard (Jan Malmsjö), and the two fall in love and get married. Soon, Emilie, Fanny and Alexander give up their life of privilege, and family, to move in with the Bishop and his family, and the dynamics between the two could not be any more pronounced. Whereas their previous life was filled with life and love, they are almost shut-ins with the Bishop, whom has insisted that they cut off from their previous life, as if they are born anew with him. All the while, Alexander has seen images of his father, as well as premonitions of the Bishop’s past family, leading to an even more strained relationship between them which leads to physical abuse and punishments like locking him in the attic. The duality of this is fascinating to watch, and the ways the kids react to everything they experience are remarkable to watch. There is not a false acting note in any of the actor’s performances, with a scene between Guve and Malmsjo probably being one of the finest scenes Bergman has ever directed, as we see Alexander stand up by the Bishop, unafraid to be honest with him, even if it means a lashing.

The film is about family, to be sure, but it has some other things on its mind, as well. It’s about the way children can feel predisposed to believe in the supernatural, and the way Bergman brings that idea into the film is simple and beautiful. It’s about the toxic nature of relationships with a narcissist who insists on having things their way; that, in and of itself, presents an interesting contrast in Gustav and Alma’s relationship. Ultimately, though, it comes back to family, and how- regardless of the chaos that can come out with a particularly large one- the best ones, despite their faults, are always filled with love and affection towards one another, and are worth fighting for. It’s striking how a filmmaker so consistently drawn towards mortality and existential crisis like Bergman can find hope in this situation, and make me feel genuinely inspired by his ability to do so. That’s why he was one of the greats.