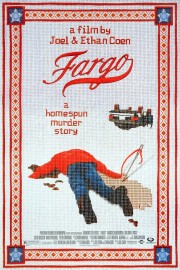

Fargo

I can’t be the only person who wasn’t quite sure what to make of the Joel and Ethan Coen’s 1996 masterpiece, “Fargo,” when I first watched it. It’s unlike any other film I’ve ever seen, and– up until their 2007 Best Picture winner, “No Country for Old Men” –it’s the bleakest movie they’ve ever made. And yet, there’s a blast of humanity shot through the film that makes it anything but despairing.

That blast of humanity is in the form of Marge Gunderson, the pregnant police chief played by Frances McDormand, Joel Coen’s wife. She comes into the film after all of the events of this outrageous tale have been set in motion. Originally looking into a triple homicide outside her hometown of Brainerd, she then finds herself investigating a much stranger crime– the kidnapping of a housewife by two men (Steve Buscemi and Peter Stormare) hired by the husband, Jerry Lundegard (William H. Macy). On the surface, Marge has the look of just another small town police officer, almost like a female Andy Griffith, but after she accurately describes what happened at the scene of the homicides, we know she’s going to figure things out.

That’s good, because we’re not even sure we understand. The only reason Jerry hatches this absurd scheme? He needs money from his stingy father-in-law (Harve Presnell), who wouldn’t give it to him otherwise. He tries to call it off when a potential business deal looks like it might happen, but he isn’t able to get in touch with the kidnappers in time. It’s probably just as well, because the deal doesn’t go his way, leading to the most frustrated scene of getting ice off of a windshield I’ve ever seen outside of my own life. That’s second only to when Buscemi’s character pulls into long-term parking at an airport to steal a license plate for the car Jerry provides, and he has to pay $4 for just going in and out for a matter of minutes, in absurd hilarity…

…Well, ok, maybe the accents are the craziest, funniest things in the movie. The regional accents sported by Marge, Jerry, and others are bizarre, and kind of mesmerizing. They establish not only the small-town environment that pervades throughout the film, but also sets the tone with a level of reality that, sometimes, borders on the surreal. That’s fitting because the film claims to be “based on a true story” at the outset, yet still has the disclaimer of being “fictitious,” and any similarities to anyone, living or dead, are entirely coincidental. The Coens can be tricky like that, whether they’re adapting someone else’s work like they did in “No Country” or “True Grit,” or telling their own story as they do here and in their next film, the legendary “The Big Lebowski.”

That surreal tone I mentioned also comes from the snow that covers the terrain throughout the film. This is some of the best work cinematographer Roger Deakins has done in his career, and part of it comes from the decision he and the Coens made to shoot the film like a western (more like a northern, really), which makes sense, because the film’s morality, where money is more important than human life, is straight out of the old west ethos the Coens would also explore in “No Country” and “True Grit.” There are a lot of wide shots of landscapes, covered as far as the eye can see with snow. This is part of why McDormand’s Oscar-winning performance, and the tender scenes between her and her husband, are so important to the film. Marge isn’t Wyatt Earp, but she’s a Hell of a detective, and it’s because of her loving, sympathetic nature that we can accept such odd lines as, when Jerry high tails it during an interview, “Oh my gosh, he’s fleeing the interview! He’s fleeing the interview!” By this point, she’s more than earned our respect, and when she confronts Stormare’s stoic sociopath as he’s getting rid of Buscemi’s body in that woodchipper (a scene made more unnerving because of the snowy background), we fear for her life, of course, but also see a steely resolve that allows us to know that, for her, things will work out in the end.

The final piece of the film’s evocative, comedic puzzle comes from the score by Carter Burwell. The composer on most of the Coens’s films (the exception being the song-heavy, “O Brother, Where Art Thou?”), his lonely, mournful score captures the desolate landscape the Coens and Deakins show us perfectly. This is the score that establishes Burwell, who’s never been nominated for an Oscar, as one of the great, individual composers in film history, and it comes from the effortless ways he uses orchestration to turn his distinctive theme for this film into both one of menace, as well as one of tenderness, as it plays over the final images of Marge and her husband, who share a lovely scene after all the craziness of this crime has subsided. The tenderness is what I remember most about “Fargo,” even more than the pitch-black comedy and shocking violence, because it turns a good procedural into a great work of art that can be watched over and over, and never get old.