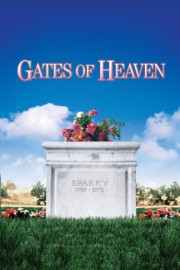

Gates of Heaven

It’s fairly safe to assume that, if you know of Errol Morris’s “Gates of Heaven,” it’s because of Roger Ebert. It’s greatness was championed vigorously by Ebert and Gene Siskel in the late ’70s, and Ebert even included it as one of the 10 Best Films he’d ever seen in 1992 when he made a list for Sight & Sound‘s famous poll that year. He made it one of the first entries into his “Great Movies” series, and it is now part of The Criterion Collection, long established as a masterpiece of documentary filmmaking. That’s a lot of weight to place on a film Morris wasn’t even sure if he would complete, at the time, but it is an invaluable passageway into not just the documentary form, but Morris’s work itself. Even then, he was singular as an artist.

For anyone who is not aware, Morris’s film is about pet cemeteries, or rather, one pet cemetery, first run by Floyd McClure, who envisioned giving people the gift of an eternal place to come and visit their beloved pets who had passed away, and Calvin Harberts, who ran the cemetery after it went under, and the animals laid to rest there needed to be dug up and moved to Harberts’s Bubbling Well Pet Memorial Park. Another filmmaker might have focused on the success and failure in business between McClure’s passionate devotion to Foothill Pet Cemetery and Harbert’s successful running of Bubbling Well, but Morris is more interested in the topic on a more elemental, emotional level. For him, the interest lies in the psychology of humans who not only want to afford others peace of mind when they lose a beloved pet, but the humans whose attachment to their pets is akin to their attachment to people. That alone makes “Gates of Heaven” indispensable viewing.

When you see a title like “Gates of Heaven,” you automatically think it’s going to be some sort of religious film- heck, it sounds like an evangelical drama about coming to God that you’d expect from the likes of PureFlix or Affirm Films. It’s easy to understand why you might think that, but it could actually be a blessing in disguise for a faithful moviewatcher to find “Gates of Heaven,” because there aren’t too many other films that search for spiritual meaning quite like this one does. Late in the film, there is a woman who has buried her dog at Bubbling Well who says, “There’s your dog; your dog’s dead. But where’s the thing that made it move? It had to be something, didn’t it?” Has the question of what happens to us after we die ever been boiled down so succinctly? This is just a woman whose dog has died, and she poses the central existential question of spirituality with an eloquence most scholars and theologians might be envious of. Morris didn’t have to go searching for “experts” on the nature of the soul to get this insight- he just had to set his camera down, and ask them to speak on their life. This is a level of depth and purpose Morris captures effortlessly in every project, whether it’s this film or “Vernon, Florida” or “Fast, Cheap & Out of Control” or his recent Netflix series, “Wormwood,” and he is just wanting to talk to his subjects, and let them reveal themselves. That such a probing and unique body of work started with a newspaper article in a California newspaper, and a bet with Werner Herzog, is a gift to moviegoers everywhere.

My 40 years on Earth has seen many animals cross my path in life, and with the possible exception of the cockatoo my mother brought down from Ohio in 2002, there aren’t any big ones I look back on with anything but fondness, and when they have passed on, it’s hurt. My grandparent’s dog C.P. when we still lived in Ohio. My family’s dogs, Charcoal and Buffy, after we moved to Georgia. The multitude of cats my mother has welcomed into our home, and the three cats my wife and I have now, all have unique places in my memory banks. As I’ve grown older, the sting of losing a pet has become greater, and I’ve begun to cherish my time with animals in my life all the more. The many cats and dogs my parents and I have had are all gone now, and going over to my mom’s house now with the quiet of no pets is surreal, and I know it is surreal to her. Where’s the thing that made it move? It had to be something, didn’t it? Loved ones come in all shapes and sizes, and Morris gets to this fundamental, emotional truth better than anyone has in his first film. “Gates of Heaven” gives us a better understanding of life, whether we have four-legged animals to share it with or not.