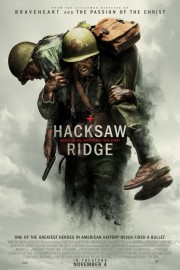

Hacksaw Ridge

If Mel Gibson is ever going to become a bankable name in cinema again, I have a feeling it will have to be as a director. A decade of controversies related to anti-Semitism, racism, domestic violence and alcoholism have it all but impossible to accept him as an leading actor, although his villainous role in “The Expendables 3” fit the recent narrative of his life effectively. Unfortunately, his controversies have led to the cancellation of two films as a director that would have fit well into his interest in bold films told in unlikely languages. The fact that “Hacksaw Ridge” seemed to come out of nowhere, and is being marketed not with his name but as being from the “director of ‘Braveheart’ and ‘Passion of the Christ’” shows how far he has fallen (although he has been making the media rounds for the film). If the film, and audience interest in it, is any indication, however, his storytelling instincts behind the camera may be essential to him becoming a vital voice in American cinema again.

Wait, a “vital voice in American cinema? Was Mel Gibson ever that?” That is a fair point, but I would argue that he was. As an actor, he was always one of the most underrated of the ‘80s/’90s action stars, capable of depths of emotion in Hollywood roles that many of his peers weren’t able to reach in films such as the first two “Lethal Weapons,” “Ransom,” “Conspiracy Theory,” “Signs” and “Maverick” while never losing the edge that made him a star to watch in the likes of “The Road Warrior” and “The Year of Living Dangerously.” This on-screen persona shown compellingly in the VOD release, “Get the Gringo,” while into uncharted emotional territory with Jodie Foster’s “The Beaver,” wherein his off-camera demons seemed to collide with his natural on-camera charisma. Behind the camera, he followed his 1993 debut, “The Man Without a Face,” with three increasingly bold, and violent, cinematic epics, the latter two of which increased the authenticity by being spoken in the languages of the time. In the last three films, we have epics of the soul that are written in blood as a legendary 13th Century Scottish freedom fighter inspires many for a battle for his country’s independence (the Oscar-winning “Braveheart”), the defining moment of the Christian faith unfolds to a backdrop of savagery in first Century Judea (“Passion”), and a Mayan husband taps into his primal self to protect his village in 16th Century South America (“Apocalypto”). For his fifth film, Gibson has another bloody epic in store as he tells the story of Desmond Doss, a Seventh Day Adventist who enlisted to the Army in WWII, and was the first conscientious objector to win the Medal of Honor after he saved 75 soldiers during the Battle of Hacksaw Ridge without firing a bullet. Because Doss has to fight to practice his faith within the confines of the Army, and is almost court-martialed for it, it’s hard not to see the film as a bit autobiographical for the the conservative Catholic Gibson, who felt his own faith being under attack when charges of antisemitism arose during the lead up to “Passion of the Christ,” and again during his drunken outburst after he was pulled over in 2006. Thankfully, Gibson cares enough to tell the story as written by Andrew Knight and Robert Schenkkan without bringing too much of his own baggage to it, and allows Andrew Garfield (in his best work to date) to take us on the emotional journey Doss takes.

The persecution complex Gibson has displayed in his directorial efforts to date is unmistakable to detect, but there’s a layer to Doss’s story that hints at a truly apologetic tone in Gibson we haven’t really gotten elsewhere. Another reason Doss’s story may have resonated with Gibson is because when we first see him as a child, Desmond and his brother Hal are fighting as brothers do. This aggravates their mother while their father, Tom (a powerful Hugo Weaving), a WWI vet who lost many friends both during and after the war, is pleased to see it until Desmond takes a brick to Hal’s head, almost killing him. Tom has developed a drinking problem, and later in the film, we see Desmond envisioning a moment where he has to protect his mother from Tom’s drunken rages that may or may not be reality. Doss’s belief in non-violence, guided by faith, is infused by this moment, and we frame his values not just in terms of his faith, but also a desire to make up for what he almost did to Hal, and wanting to not become a man like his father. Is it possible that Gibson is not only working to atone for his own sins, but also try and distance himself from his controversial father? Again, it’s hard not to read autobiography in Gibson’s films, especially as a director, after he poured his heart and soul into “The Passion of the Christ.” Still, the motives for telling Doss’s story are Gibson’s alone- he’s responsible, first and foremost, with telling the story, and though it sometimes moves in fits and spurts before we hit the battlefield as Desmond falls in love with Dorothy (Theresa Palmer), Gibson doesn’t leave any fat on the narrative- you just have to ride through it until you get to the battle scenes.

The second half of the film is devoted to the Battle of Hacksaw Ridge, which takes place on a plateau that the soldiers can only get to by climbing up a steep wall face. That imagery, shot by “Knowing’s” Simon Duggan, is striking enough, but the fighting when they get to the top is as accomplished as anything Gibson has ever directed. The battle wasn’t quite as enthralling as “Braveheart’s” Battles of Stirling and Falkirk, or “Passion of the Christ’s” brutal Scourging scene, but it’s powerful stuff to watch, and fully engaged in character and battle tactics as we see the Japanese swarm Doss’s platoon, and the characters we followed in bootcamp and how they deal with the carnage. If nothing else, Gibson has shown himself to be a master of bloody action revealing spiritual truth within his characters. True, his cinematic style is familiar to students of Kurosawa and Welles, but the stories, cliches and all, are unique to Gibson and his view of the world through his faith. Whether we agree with that is one thing, but as “Hacksaw Ridge” shows, he is a singular talent as an actor who turned to directing, and bares his spiritual struggles for all to see.