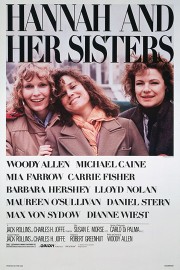

Hannah and Her Sisters

It’s easy to see why people think Woody Allen makes the same movie time and time again. He tends to follow similar patterns of screenwriting and story construction and themes. How he puts those together is the difference between great films like “Hannah and Her Sisters” and bad films like “Celebrity.” Part of a great run of his in the 1980s that included “The Purple Rose of Cairo” and “Crimes and Misdemeanors,” “Hannah and Her Sisters” is the writer-director at his neurotic finest.

For most of my movie watching life, I’ve known “Hannah and Her Sisters” mainly for two things- that it was made by Woody Allen, and that Michael Caine won an Oscar for his role as Elliot, but was unable to accept it because he was stuck filming “Jaws: The Revenge” in the Bahamas. Now, I’m making an effort to delve more into Allen’s films, and finally watching films like “Hannah and Her Sisters” is a big part of that. It deserves being discovered, as Allen (who appears in the film as a TV comedy writer who is going through an existential crisis when he has an ear infection that he worries is much worse) digs into the dicey relationships Hannah (played by Mia Farrow) and her sisters Lee (Barbara Hershey) and Holly (Dianne Wiest) have with men, including Elliot (who is presently married to Hannah but falls in love with Lee), Allen’s Mickey (who was married to Hannah and later went on a terrible date with Holly), and Max Von Sydow’s Frederick, an older artist whom Lee is currently living with, over the course of one year, from Thanksgiving to Thanksgiving.

With ensembles such as this, every bit of attention must be paid to scenes, because each scene has some fundamental piece of the narrative puzzle to it. The story feels, at times, like it focuses on Elliot and Mickey, but it really does boil down to Hannah, Lee and Holly. The romantic relationships they have in the film drive the film, even if it doesn’t always seem to be the case. This is part of Allen’s gift as a writer, in this film, and no scene feels wasted by him as a storyteller or the actors. Even brief moments from the likes of Sam Waterston as an architect whom Holly, a recovering drug addict, shares feelings for with April (Carrie Fisher), her friend and a business partner in a catering business, are important for the film’s emotional thrust, although the primary figures are Hannah, whose marriage to Elliot feels at risk when he falls in love with Lee, and while they share a moment of passion together, Elliot is definitely the one pursuing things with her. It’s not the first time that Hannah has shared significant others; she was married to Mickey before she married Elliot, but they split up after it was discovered Mickey was infertile. Mickey also went on a horrible date with Holly, later. The love lives of these sisters are complicated, and there really aren’t any easy choices for them.

Woody Allen’s writing of relationships and familial dynamics has rarely been as deft as it is here (and he, rightfully, won an Oscar for this film), and everyone has standout moments. The Oscar-winners, Caine and Wiest, have the standout roles, but I don’t know that I would say that they are the best performances in the film. Allen is essentially playing himself, although it is, probably, one of his best personal performances in that type of role. Farrow and Hershey are at least as good as Wiest is among the three sisters, and Carrie Fisher and Julie Kavner (as Allen’s assistant) are strong comedic presences when they are on screen. This is more of a collectively strong ensemble than a film where you can pinpoint one performance as being better than the other, and that’s when Allen’s films are at their strongest. Of course, the writing and directing of the legendary neurotic is also important for success, and on that criteria alone, “Hannah and Her Sisters” stands out among Allen’s work.