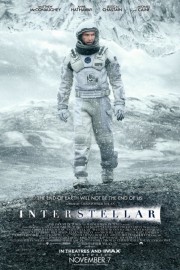

Interstellar

Christopher Nolan reaches for his most ambitious heights with “Interstellar,” which is saying something considering his Oscar-winning Best Picture nominee, “Inception.” This film not only features the most extensive use Nolan has made to date of the IMAX camera, but also enough “hard science” concepts to give Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” a run for it’s money in the awe and intellect department. That it ends up closer to Peter Hyams’s “2010: The Year We Make Contact” has less to do with the ways Nolan’s film falls short (although it has a couple of places that do), and more to do with how singular Kubrick and Clarke’s accomplishment was.

This was originally going to be a movie Steven Spielberg directed several years ago, and while I really want Spielberg to return to the sci-fi genre at least once more before he’s done, having Nolan take on his brother Jonathan’s script moves the director of the “Dark Knight” trilogy and “Memento” out of his comfort zone, forcing him into real emotional territory. Yes, there have been emotional narratives in his previous films, but they’ve largely felt at a distance compared to the considerable cinematic techniques and storytelling trickery at work. Fair enough, but it’s also resulted in a reputation for Nolan of being an icy filmmaker emotionally, although I would argue he plums real depths, in his own way, in “Memento,” “The Prestige,” and “Insomnia.” In “Interstellar,” he aims straight for the heart, and for the most part, he succeeds exceptionally well.

One of the biggest things that stands out in “Interstellar” is Matthew McConaughey, who follows up his triumphant work in “Mud,” “Dallas Buyers Club” (for which he won an Oscar), and TV’s “True Detective” with another fantastic performance as Cooper, a former NASA pilot whose priorities shift when food resources begin to deplete on Earth, and he has to turn to farming. The Earth is dying, and diseases are killing off a different crop each year. After his wife dies, he is left to farming with his father-in-law (John Lithgow), who helps him raise his children (Tom, played by Timothée Chalamet, and Murph, played by the exceptional Mackenzie Foy). While Tom takes naturally to farming, Murph is a lot like Cooper: intelligent, a dreamer, and passionate about exploring the universe. One day, during a dust storm, they see a message in the way the dust fall in her bedroom. It’s coordinates, and it leads them to a secret NASA installation where scientists (led by Michael Caine and Anne Hathaway, who plays Caine’s daughter) are desperately working on a space mission to find a planet. After previous secret missions, there are three possibilities, all accessible through a wormhole next to Saturn. Will any be viable possibilities? The bigger question is whether Caine’s professor be able to solve a key part of the equation necessary for people on Earth to survive before it’s too late. It’s a race against time for Cooper, Hathaway’s Dr. Brand, and two others, with a personal stake that goes beyond saving humanity for Cooper (who has a falling out with Murph that will haunt both) and Brand, and inform choices they make on the voyage.

If you don’t really figure out all of the science in “Interstellar,” don’t worry, because believe me when I say you aren’t alone. (Besides, no less than Neil deGrasse Tyson has weighed in, and there are…issues.) The biggest benefit for a film so dedicated to “hard science” concepts isn’t in getting us to necessarily understand them, but to engage our curiosity in them, and as Dr. Tyson showed with his updating of the Carl Sagan miniseries, “Cosmos,” earlier this year, that is very possible to do with a lot of people. Even though it doesn’t hit the same intellectual height of “2001,” the film nonetheless occupies scant company when it comes to sci-fi cinema centered around ideas, with “2010,” “Contact,” “Solaris” (both versions), “THX-1138,” and “Metropolis” rounding out the exclusive list, with last year’s “Gravity” finding an interesting middle ground that fits “Interstellar” pretty well. One of the early scenes in the film has Cooper being told that Murph got into a fight at work when a classmate said that the lunar missions were staged for Cold War propaganda against the Russians, which has been adopted as the official history in textbooks at Murph’s school. Some critics have pointed to such revisionism as ludicrous, but when you see the great divide in knowledge every time science is challenged on our TV screens, it’s not hard to see why the Nolan brothers included such a drastic example in this film. Their central thesis during the first scenes of “Interstellar” is that mankind lost something profound when survival became the primary objective in our existence over exploration, and that without exploration and risk, survival is impossible. It’s a powerful message that’s important to the emotional pull of the film, because it’s that idea of exploration as a necessity to live that will drive Murph (played later in the film by Jessica Chastain) to make critical choices when hard truths are revealed. Of course, throughout this entire discussion of how “hard science” is essential to “Interstellar’s” success as a film, I’m hardly even touching on the concepts such as Einstein’s Theory of Relativity or the work of Dr. Kip Thorne, who not only collaborated with the visual effects artists, but whose ideas inspired the narrative of the film, but the less I say about that part, the more surprising the film will be as we see it play out.

Reading over some reviews and thoughts about the film, there are legitimate questions to be asked about the story as a whole, which seems focused on a very American point-of-view, and that’s fair. What cannot be questioned, however, are the film’s significant artistic values, starting with it’s look, although there’s a big exception I’ll make later. A “2001”-like game changer, this is not, but the visual effects artists, cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema, and production designer Nathan Crowley do remarkable work that allows us to believe this trip through time and space, as well as the stark landscape Earth has become in this near-future. I have yet to watch it in the native IMAX it was filmed in, and I truly hope to in the near future, but the film is beautifully seen even in it’s standard framing. In particular, the scenes of space flight, and on the respective surfaces of two of the planets under consideration for human habitation, are tactile and evocative, setting up moments of great tension and wonder as mankind tries to find a place to call it’s new home. As he has with their past few collaborations, editor Lee Smith helps make deliberate editorial choices that increase suspense and keep the film moving, despite it’s nearly 3-hour running time. Aiding in that responsibility is composer Hans Zimmer, who moves far away from his comfort zone, and established sound with Nolan, to create a score of striking feeling and objectivity that will bring to mind the soundtrack of “2001” as recontextualized from the musical mind of “Inception.” There are no waltzes or droning ostenato figures, but the musical footprints in both works are evident, showing a fascinating evolution for the composer. The one technical place where “Interstellar” falters is in a sound mix that focuses too strongly on the center channels, resulting in a drowning out of a lot of the dialogue by way of the sound effects and music too many times, meaning things get lost in the narrative. I’ve heard stories of some screenings being just fine, but even if that’s the case, people shouldn’t have to fight to hear the dialogue aurally at any time during a film.

I hate leaving my review of “Interstellar” on a sour note, because there’s a great deal about the film I greatly admire, if not outright love. The film’s take on science as a fundamental piece of human life, and how our curiosity and risk can lead us to do great things, speaks to the part of me that was awakened by the aforementioned reboot of “Cosmos” earlier this year. As someone for whom science fiction is my favorite film genre, I was excited by the sights, ideas, and musical sounds the film gave me to stew over. And as a fan of Christopher Nolan’s since I first saw “Memento” in 2001, I feel appreciative that the director pushed himself out of his comfort zone, and reached for something that is not only big in scope and theme, but also capable of an emotional core sometimes lacking in his films. It may not always succeed, but it engaged me in a way few other films have this year, and that’s a great compliment regardless of who you’re talking to.