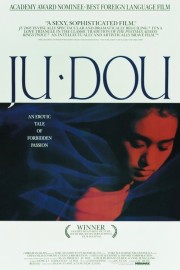

Ju Dou

After his duel martial arts epics, “Hero” and “House of Flying Daggers,” were released in America in 2004, I first began to watch the earlier films of Zhang Yimou, and obviously, the films like “Raise the Red Lantern” and “Shanghai Triad” were nothing like his later films I had seen. His dramas in the early ’90s were intimate, personal and provocative as Chinese cinema began to become available on the world stage, with Yimou being the biggest name. (He would go on to produce the opening ceremonies for the 2008 Olympics.)

Of that flurry of viewing, I think his 1990 drama, “Ju Dou,” probably had the strongest effect on me of all of those films, and rewatching it, it was interesting to see that hold up. The film is based on a novel, and was banned in its homeland for a couple of years, and it’s easy to see why. It centers on a young woman- played by Yimou’s muse at the time, Gong Li- who is married to an old dye mill owner, but becomes involved in an affair with the man’s nephew. This is a movie that challenges patriarchal mindset, regardless of the culture, and gives the woman a degree of control over her life. Not complete control, but enough to where she can make some decisions for herself, and over whom she loves. Not everyone in her life is so open-minded, though.

After the credits role, we see Yang Jin-shan (Li Wei) take a wife, Ju Dou (Li’s character), and we start to see the pattern of their marriage as life in the dye mill commences. At night, Jin-shan forces himself on Ju Dou, not just in hopes of her producing an heir, but for his twisted pleasure. Listening on in the night is his nephew, Yang Tian-qing (Baotian Li), who is taken by his aunt’s beauty, and horrified by how his uncle treats her. One day, he and his aunt make love, beginning an affair that will take several twists and turns, especially when Ju Dou becomes pregnant with a son.

Sadly, I had to watch this film on YouTube, but the Technicolor process Yimou used to shoot it with cinematographers Changwei Gu and Lun Yang is nonetheless striking to watch. And although Yimou shoots the love scenes without gratuitous nudity, it matters little as the sensual nature of the scenes comes through effortlessly anyway, while we only hear the pain that Jin-shan puts her through when they are first married, and before an accident that will paralyze him from the waste down. There is a lot I’m actively not saying about this story, because the film deserves to reveal its wicked twists and turns itself, without me discussing them here. What I do want to discuss, however, is Gong Li in this film, and though she has been seen as an icon, I think a lot of people forget how fantastic she really is, probably because modern American audiences are more familiar with films like “Memoirs of a Geisha,” “Miami Vice” and Yimou’s “Curse of the Golden Flower” than her earlier triumphs with the director, which are not as readily available. What resonated with me now, and when I first watched “Ju Dou,” was the complicated emotional landscape of the film, which shows how marriage can be a trap, and a genuine love outside of that can set someone free. Society chastises cheaters, but for someone like Ju Dou, who feels trapped in a violent, and loveless, marriage, there’s no other way for her to feel free and able to live a satisfying life. The society around Ju Dou, however, is not one that celebrates individual freedom or love but rigid societal rules, which will trap Ju Dou even after her husband dies, and they should be free to love each other openly. This is probably the best performance she delivered for Yimou, and even though I remember “Raise the Red Lantern” as a great film, this might be their best one together.