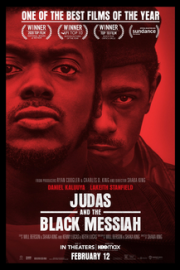

Judas and the Black Messiah

**Seen at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival.

Shaka King tells the story of Fred Hampton’s final months, before he was assassinated by Chicago Police and the FBI, in a fairly conventional narrative structure, largely through the eyes of William O’Neal, and car thief whom the FBI recruited to infiltrate the Black Panther Party, which Hampton was the chairman of in the late 1960s. One of the shrewd narrative choices he and his co-writers (Will Berson and Kenny and Keith Lucas, who co-wrote the story) make is that we never really get a handle on whether O’Neal believes in what Hampton is espousing. We know that he’s for equal rights, of course, but whether he feels the type of revolutionary action Hampton is trying to mobilize is justified is uncertain. All we know is that, in 1990, after giving his first public interview about the events for TV, he killed himself, as the guilt over his actions ate away at him.

Between this, “One Night in Miami,” and “MLK/FBI” recently, we’ve been given fascinating films that study about some of the most substantial leaders of the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s, and the outright hatred they were met with by the federal government. Watching “Judas and the Black Messiah” last night, I couldn’t help but wonder what might have happened had the government not committed itself to destroying these men, and if they had lived past the ’60s. What would America had looked like? Would Hampton had lived to see Obama elected President? Would we have ever had the national reckoning with systemic racism and the lingering effects of slavery we so desperately need now? Would Black Lives Matter still exist as a movement? Unfortunately, I can probably answer all of these questions pretty easily. White privilege and racism is, sadly, a fundamental truth of the American experiment, and the government has long needed it to assert control over minorities. Plus, white people in America have never done well with change that benefits those who seek to advance the fundamental rights of others. These thoughts have no bearing on my feelings on the movie; I just wondered about them during the film, and wanted to share them.

The film being seen from William O’Neal’s perspective more than Fred Hampton’s is important to its success. It makes it feel less like a stale biopic and more like a thriller, as O’Neal has much to lose if he doesn’t comply with the FBI, represented primarily by his handler, Roy Mitchell, played by Jesse Plemons (although we do see J. Edgar Hoover in the film, and he’s played by the great Martin Sheen). Why, if he was just a car thief, did the FBI center in on O’Neal to make their spy on the inside of Hampton’s operation? Because he was also impersonating an FBI agent in his schemes to do so. Shaka King doesn’t excuse O’Neal’s behavior, and neither should we, but as we see the walls start to close in on Hampton through O’Neal’s intelligence being offered, we also see that it is simply a part of the government’s attempts to destroy Hampton, and often, the FBI uses the threat of prison to hold O’Neal captive long after their plan, which he is not fully aware of, is in motion. His guilt in undeniable, and palpable, and he has been just a pawn used by the government towards their endgame rather than a villain. The Judas moniker is fitting; he was used as a sacrificial lamb as part of a larger purpose being fulfilled.

Even though the film is from O’Neal’s perspective, Fred Hampton is not just painted with swift brush strokes in his characterization, or mythologized as an individual; he is seen as a man, faults and all, with ideas that make him a complicated one to think about. When Hampton discusses revolution, we automatically think of the use of force, but that’s only a portion of his efforts. He helped found the Rainbow Coalition and creates an alliance between major Chicago street gangs to help institute social change. Like Dr. King and Malcolm X, he wants to create a better America for all, and that’s one of the things that, as we start to really learn about these men, they were so dangerous, not just for the government, but the establishment and those who benefit from government, in general. Revolutions are not just about bloodshed; it just happens to be what catches the most attention from the elites.

There are three fantastic performances at the heart of this film. The one that everyone has centered around is Daniel Kaluuya as Hampton himself, and seeing him move from “Get Out” to becoming one of the best actors in Hollywood at conveying stone-cold intensity in roles like this and “Widows” is kind of thrilling, but as Hampton, he also has a warmth that is palpable and affecting. A lot of those moments come with Dominique Fishback, who plays Deborah Johnson, a staffer who becomes Hampton’s fiancee, and mother to his son, whom will be born after his death, and with Deborah, continued on his father’s legacy with the Black Panther Party Cubs. Fishback gives a wonderful performance as Deborah, who wants to see Hampton hone his rhetoric, and use his voice more emphatically. Their final moments together are heartbreaking. Finally, there is LaKeith Stanfield as O’Neal. From his first moments onscreen, O’Neal is characterized as a smooth operator who can make anyone believe anything, and Stanfield continues that throughout the film, although the anxiety of his situation becomes a primary emotion at a point, and he sells that, as well. His performance is as important as Kaluuya and Fishback’s are, and he delivers; all three are legs upon which this film stands. It’s a sturdy foundation for a film that burns with the passion of its performances, which give us much to think about, but might be just an interesting biopic that could be easily forgotten without them.