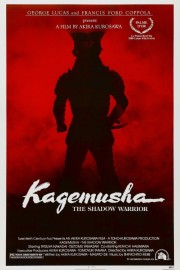

Kagemusha

The influence Akira Kurosawa had on George Lucas, and especially “Star Wars,” is evident the more you dig deeper into the Japanese master’s samurai films, with “The Hidden Fortress” and “Seven Samurai” being the most obvious inspirations. In the late ’70s, Kurosawa had trouble putting together funding for his return to the samurai genre, an adaptation of King Lear he’d wanted to make for a while now. Times had hit the filmmaker tough in his native Japan, and in 1975, he had to look for Russian financing for “Dersu Uzala.” As a rehearsal for the Lear adaptation, which he would finally make in 1985 in his masterpiece, “Ran,” Kurosawa decided to make another samurai epic, “Kagemusha.” When Toho Studios ran out of money to finish the film, Lucas and buddy Francis Ford Coppola were able to convince 20th Century Fox, which had just made a fortune off of “Star Wars,” to put up the money to finish the film. As Darth Vader said in “A New Hope,” “I was once the learner, but now I am the master.” The resulting film, which I’ve now seen twice, doesn’t quite resonate with me the way “Ran” or Kurosawa’s earlier samurai epics do, nonetheless finds an intriguing emotional core in its story, which, like “Ran,” also deals with an old leader who tries to impose his will long after he is no longer in power.

Rather than Shakespeare, Kurosawa takes inspiration for “Kagemusha” from Japanese history. Specifically, 16th Century Japan. The country is in a period of constant civil war, although some sense of peace has been kept by the dominance of Shingen (Tatsuya Nakadai) of the Takeda clan, and his resolute ability to hold off his opponents. One way in which Shingen, old and frail after years of war, accomplishes this is his use of double, and with him starting to feel his age, he sees the importance of having one around more than ever, and not just on the battlefield, where his brother has done that many times. They have, in fact, found someone who, in exterior features, looks exactly like Shingen in a thief from Northern Japan (also played by Nakadai). With this rouse in place, Shingen, who was an actual Japanese warlord of the time, feels secure in his ability to stave off attack from his rivals, Tokugawa Ieyasu (Masayuki Yui), Oda Nobunaga (Daisuke Ryû) and Uesugi Kenshin (Eiichi Kanakubo). One night, Shingen visits the battlefield when he is shot by a sniper, and mortally wounded. He asks that his generals keep his death a secret for three years, so that his enemies are kept at bay. When he finally dies, it’s up to the thief, known as Kagemusha (or “political decoy”) to serve in a far more important role than he expected to, which also includes charming Shingen’s wives, playing with his grandson, Takemaru (Kota Yui), whom is quite fond of Shingen, and keeping the whispers of his enemy’s men about his death as nothing more than rumors. A turning point, however, comes when Takeda Katsuyori (Ken’ichi Hagiwara), Shingen’s illegitimate son and Takemaru’s father, takes his anger for his father’s ploy and does something that draws the conflict to a critical juncture when he tries to take a castle even his father had been unable to do. Meanwhile, the thief is overwhelmed by his responsibility, but gradually takes to his charge in a way that makes his eventual fate poignant and powerful to watch.

One of the things that struck me when I first watched “Kagemusha” many years ago, and again when I watched it yesterday, is how little action there really is in the film. Many of the battle scenes are shown in the ways the characters react to the action rather than how the action unfolds. That is a crucial decision on Kurosawa’s part, as one of the themes of the film is how characters perceive what is going on around them based on what they see. The spies of Shingen’s rivals know the ruler was wounded, and they see things that imply that he is dead, but Shingen’s generals stage an announcement that punctures holes in their thought process, even if that original thought remains. Shingen’s wives are accepting of the thief’s outside appearance of looking like Shingen, but are kept at bay with lying with him for fear they will notice something that isn’t there, like a battle wound they would recognize. At the end, after he is found out by friend and foe alike, the thief is stripped of his responsibilities, and Shingen’s armies meet his adversaries for the Battle of Nagashino, but rather than show the action, we see the aftermath of the action, and how Katsuyori (now in charge of his father’s army) and an exiled Kagemusha (looking on at the outskirts of the battlefield) react to what we hear on-screen, which implies a slaughter we get confirmation of when Kurosawa finally does show us the battlefield. The resulting effect is as thrilling as anything in his previous samurai films (and would come in his next film, “Ran”), but powerful in a very different way that hints at what was to come with “Ran,” where the action commented on the film’s themes rather than existed just to entertain. This is the work of an artist still finding new ways to express himself in his art, and finding people he inspired who could help bring it to the masses is one of the surpreme pleasures (and sadnesses) of the latter part of K’s career. (Other disciples, Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese, helped the master out on his 1990 tone poem, “Dreams.”) How was a legendary filmmaker reduced to having to scrape for funding at the end of his career, long after he had established himself as one of the great masters of the art form? I’m sure Lucas and Coppola were asking themselves the same thing, but were more than happy to help him out. After all, his work is part of their own on a molecular level, and rightfully so.