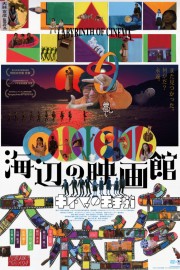

Labyrinth of Cinema (Fantasia Fest)

**Seen for the 2020 Fantasia International Film Festival**

I think you can tell when filmmakers have a sense that they are near the end of their lives in the films they make at that time in their lives. I’m not saying that they know, unequivocally, that they are making their last film (or near their final movie), but the themes, the visual pallets, the ideas all feel like they are coming from an individual who knows they are probably not long for this world. It’s fascinating to see how different filmmakers, in looking at the films they made at the end of their lives, approached mortality, memory, and the artform itself. Tarkovsky had a man trying to bargain for his love one’s lives when faced with the possibility of WWIII in “The Sacrifice.” Kurosawa imagined stories of art and the apocalypse in “Dreams.” Altman created an elegy for a dying artform in “A Prairie Home Companion.” And Bergman reflected on one of his most personal stories of fractured families, returning to the couple from “Scenes From a Marriage” in “Saraband.” I think Nobuhiko Ôbayashi very much knew this would be his last statement as a filmmaker (indeed, he passed away in April), and he throws all of his ideas on life, death, war and the power of cinema to drive us to a better future into “Labyrinth of Cinema.”

In every way imaginable, “Labyrinth of Cinema” is a film brimming with philosophical and cinematic ideas; there’s not a moment in this 3-hour epic where we are allowed room to breathe without some piece of information being thrown our way, whether it’s a poem by Chuya Nakahara, a movie-within-a-movie experience, a commentary on cinema from the projectionist in the film, or a reflection on what we’re seeing by Fanta G (Yukihiro Takahashi), the old space traveler who comes to the closing night of a cinema in Onomichi, where the theme is, “Japan’s War Movies.” It’s a marathon of cinema chronicling wars in Japan over the centuries, building up to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Three young men (played by Takuro Atsuki, Takahito Hosoyamada and Yoshihiko Hosoda) enter the theatre, and all three soon find themselves entering the films on-screen, much like Buster Keaton in “Sherlock Jr.,” all hoping to make sure Noriko (Rei Yoshida), a young woman film buff Mario (Atsuki’s character) met in the lobby, survive. Are they all transported INTO the film, though, or are they just imagining they are, taking in the sights and horrors of war on the screen? Even after seeing it, that’s left to your own interpretation, including the question of whether Noriko is even a real person.

The word “labyrinth,” in Greek mythology, meant an elaborate, confusing structure, and that is a good descriptor of Obayashi’s film- where reality and fantasy in the film begin and end is confounding, and it’s enough to give you intellectual whiplash watching this film. And yet, even though the 3-hour running time taxes us at times, I cannot imagine anyone not giving into its imagination and sense of purpose. The style Obayashi uses to tell this story, with many different technical tricks that play to the artificial nature of cinema, reminded me of my first experiences watching Guy Maddin’s films, which remind you constantly that they are cinema, rather than attempting to make you feel as though you are watching reality. That’s a bold approach for such a film, and even if we get tripped up by switches in time between the different “movies’ the three men find themselves in, you cannot help but marvel at the commitment, and conviction, Obayashi brings into his film on a thematic level. His premise in this final film is that cinema is more than just entertainment, but an opportunity to reflect on the past, so that we might build a better future when we leave the theatre. Using war films to get to that idea is, perhaps, a touch heavy-handed, but he does so by illuminating the self-righteous arrogance of a country who thinks its people’s primary responsibility is to the country, and sees war as a necessary means to an end. The previous week, before watching this, I finally watched “Come and See,” one of the most harrowing movies ever made, and it’s interesting to see how each film finds uniquely cinematic ways to condemn war.

This is actually my first experience with Obayashi, and I kind of wish it wasn’t. While I greatly admire the film, it feels like coming into a concert as the orchestra is performing its final piece. I’m missing all of the steps that led to this moment. Thankfully, unlike a concert, I am able to search out those steps, and they are not gone forever. I cannot wait to see where that journey takes me.