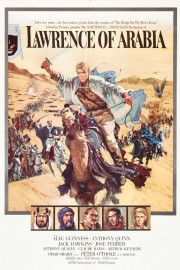

Lawrence of Arabia

When people think of films as “cinematic,” they are talking about films like David Lean’s “Lawrence of Arabia.” I’ve only seen the film once before (sadly, I’ve never seen it on the big screen), but watching it again, on Blu-Ray and my 50″ 4K TV, I doubt I can honestly say that I ever really saw it at all. An obvious complaint about watching it on home video is the inability to truly capture the experience of F.A. Young’s cinematography at home, but my setup, as it is now, came close. The clarity of the images, and the size of the screen, helped me feel like I was right in the middle of Lean’s epic, which I don’t think I felt when I watched it about 20 years ago.

It’s shocking to imagine that this film might have been lost to the ages had it not been for the work of Robert A. Harris and Jim Painten, who found crushed and rusted cans and a badly taken care of original negative in 1989 and restored it to degree than Lean was no doubt pleased with, but then again, the same was almost true of “Vertigo” and “Star Wars,” among other classic film. Thank God they did, as at least now generations of film geeks (including this one) will be able to discover the film now, and relish in the stunning scope of Lean’s masterpiece. It’s a film that sets a high bar for cinematic vision and power, although I found the last part of the film lacking when it gets into the politics of its story. That’s a minor criticism, however, for a film that swept me up in its story at the outset, and maintained its hold on me for the better part of 3 1/2 hours. I’ll let it get away with the lull, if only because the rest of the film is so inspired and amazing to watch.

The film tells the story of T.E. Lawrence, a British officer who, in World War I, brought together Arab clans against the Turks, and there’s not really much more to the story told by Lean and writers Robert Bolt and Michael Wilson than that. A lot of great movies traffic in unspoken depths and themes, but “Lawrence of Arabia” is not one of them, although it does, subtly, play with the notion of Lawrence’s sexuality. The story is about what it is about, and it’s how Lean brings it to life that gives it a power and sweeping energy. A big part of that was his casting of Peter O’Toole as Lawrence. It was O’Toole’s first film, and it’s possibly the greatest introduction any actor has had in film history. The screen presence O’Toole has is central to the film’s effect, and it’s impossible to imagine the film without him. He is a bold and boisterous force of nature, whose audacity seems to inspire the Arabs more than anything. In the second half of the film, an American journalist (played by Arthur Kennedy) begins to tell his story as a way of getting America into the war. He sees Lawrence as a useful propaganda tool and hero, and the British army agrees. This further enhances the legend Lawrence has made for himself to where we understand the reactions a reporter gets at the beginning of the film after his funeral. Like Charles Foster Kane, much is known about Lawrence, but more is unknown, and beginning the film with an echo of “Citizen Kane’s” structure, showing us his death before we witness his life, is a smart move by Lean and his writers. We start at the end, and work our way back to it. This is inspired storytelling, and it only increases with how Lean presents the story when it takes to the brutal Arabian desert.

It’s a very modern way of thinking to point out that two of the central Arab characters, Prince Feisal (Alex Guinness) and Auda Abu Tayi (Anthony Quinn), are played by white actors; at the time of its making, I don’t know that Lean’s film would have received quite the scrutiny for “whitewashing” that it would have gotten today, but it’s worth considering that both actors go beyond cliche and caricature and deliver well-balanced performances that allow you to see beyond what could be an offensive stereotype of filmmaking. As leaders who are important to Lawrence’s cause of uniting the different tribes, both Guinness and Quinn are terrific, but fittingly, the best performance is by Sherif Ali (Omar Sharif), whom we first meet when he kills Lawrence’s guide in the desert, and whom becomes an important and trusted allied in Lawrence’s attempts at unification. One of the film’s most distinct qualities among historical epics is that there isn’t a love story, or romantic interest for Lawrence. No doubt the setting and substance of the film played a big role in that, but one couldn’t help but look at it as another form of narrative subversion on the part of Lean and his writers in their pursuits of this bold project.

The bold nature of “Lawrence of Arabia” brings us back to the singular vision of Lean’s film, and the triumph that is F.A. Young’s cinematography, which can be boiled down to the single most beautiful and ambitious shot in the film. Lawrence is riding with Sherif Ali and his men across a perilous part of the desert, and are near water and a place to rest. It is at the moment when the sun is at its most merciless, and Lawrence discovers that one of the men fell off of his ride. Sherif implores him to leave them behind, but Lawrence insists on going back for him. Later, Sherif and the men have made their way to water, and a lookout is checking for Lawrence. A speck is seen in the distance, and gradually, it gets closer. It is Lawrence and the man. Jubilation overtakes the men, and they cannot believe what they have seen out of this Englishman. That scene, like the shot Lean accomplishes to make it work, defines the man of T.E. Lawrence, and the masterful scope and splendor of the film it represents.