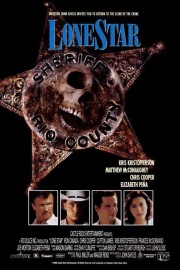

Lone Star

Rewatching “Lone Star” for the first time in almost 25 years, a phrase I used to think about in terms of certain films popped into my mind- “intimate epics.” I haven’t used it in so long that I almost can’t give you any examples of the type of films I used to describe with it, but basically, it means a small film or environment with big, expansive ideas. John Sayles’s film fits that description perfectly, as it uses a Texas town, just on this side of the border, to explore ideas universal to the American experience- racism, bigotry, and generational expectations vs. reality. Sayles tackles them all, and it is as important a discussion now as it was in 1996.

I forgot how little Matthew McConaughey is in this film. “Lone Star” came out just a couple of weeks before McConaughey had his big studio breakout in the John Grisham adaptation, “A Time to Kill,” and that heat led people to “Lone Star.” I knew he was not exactly in the main storyline, and remembered fairly well that he played the father of Chris Cooper’s character, but Buddy Deeds is not shown a lot in the film. When he is shown, however, we get important context for revelations that Cooper’s Sam Deeds will uncover when the remains of a dead body are found just out by a former rifle range by a military base that is being shut down. Buddy was a legendary Sheriff in town, and Sam is following in his footsteps, but he doesn’t sense the same pride in the job many people associate with it- he feels like he runs a hotel for drug abusers and border jumpers. His memory of Buddy is different from those in the town he serves; fathers and sons are a big part of “Lone Star.”

The remains belong to Charlie Wade (Kris Kristofferson), Buddy’s successor as Sheriff, and a corrupt and racist piece of shit. Much of our time watching Wade in the flashbacks the film contains are at a Black-owned bar in town, where Charlie enjoys getting kickbacks to look the other way at absurd restrictions, and harassing both workers and customers. One of those workers in Otis, who started out as a waiter, but took over the place from the original owner, and continues to run it in the present day. Otis (played in the present by Ron Canada) has issues with family, as well; his son (Del, played by Joe Morton) still resents Otis for not being there for him as a kid, so he’s punishing his father for that neglect by not allowing him to see his family. That includes Del’s son, Chet (Eddie Robinson), who is being pushed to be in the military by his father (the base commander of the base getting shut down), and is resentful of his father. Generational anger is a key component of “Lone Star”; Sam’s big source of disdain for Buddy is that he did not want Sam to become romantically involved with Pilar, a young Mexican woman. Pilar (played in the present by Elizabeth Peña) is back teaching in town, and they reconnect; now as adults, there are no parents to tell them who they can and cannot be with. But Buddy’s influence on the present remains strong.

The fundamental narrative of “Lone Star” is whether or not Buddy murdered Charlie Wade; all the evidence certainly appears that way. But that isn’t the only sin of Buddy’s that seems to be uncovered in the film. Institutionalized racism is still something we are struggling with in this country, and the way “Lone Star” tackles it is fascinating, and should make it required watching for everyone. Pilar has local parents up in arms with the way she is presenting history in her class, which provides depth and historical honesty to what the textbooks say- isn’t this the debate many people are having now regarding “critical race theory?” Was Buddy any less racist as Wade was, or was he just different in how he approached it? Even in the modern day, racial tensions are palpable in this town, as Black and Brown citizens seem to be asserting themselves more in local government. While we don’t see acts of racial violence in the present day scenes, white people are never happy when they feel like people who don’t look like them are getting control. Racism isn’t always up front in this town, but it’s always present.

John Sayles has crafted a great detective story, not just into the central mystery of Charlie Wade’s death, but in examining ideas of race in America, and how one generation- sometimes without intending to- passes on pains the next generation will have to deal with. I can’t think of too many films from the mid-’90s that would be more important to watch now.