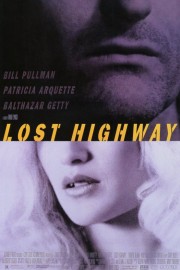

Lost Highway

I had never seen a David Lynch film before walking in to “Lost Highway” in 1997. That was a colossal fucking mistake on my part. There really isn’t a better way of putting it. As such, the film bounced off of me like a sledgehammer to the face. By the time “Mulholland Drive” ended, I was firmly a Lynch fan, though, and when the film finally came out on DVD, a rewatch had me enjoying the film slightly more than I did in ’97. I’m still kind of bored with this movie, but Lynch’s surreal style is something that I don’t mind wading through, even if the movie is as weird and dull as “Lost Highway” is.

This was the first time Lynch started to tell stories set in Los Angeles, away from the regular, peculiar joes that populated “Blue Velvet” and “Twin Peaks,” and it feels like Lynch is still trying to sort out what his Los Angeles is going to look and feel like. It’s not coincidental, I think, that he really started to lean into the horror elements of his narrative style with “Lost Highway,” “Mulholland Drive” and “INLAND EMPIRE” more than he had before; his L.A. is terrifying and not for the faint of heart, and also batshit insane in what goes on. Ordinary people get swallowed into an abyss that leaves them broken, and not the same person they were when they arrived. This is how cinema operates as an art form, and Lynch leans into it in spectacular fashion in all three films.

The film stars Bill Pullman as Fred Madison, a jazz saxophonist who lives with his wife, Renee (Patricia Arquette), in L.A. They live a relatively normal life, but let’s be honest, in Lynch land, what is normal? Soon, they begin to receive unsettling VHS cassettes implying someone stalking them, at their house. They don’t know what to make of it, and they report it to the police, but when they go to a party at a friend’s house (the friend is played by Michael Massee), their life gets even further turned upside down when Fred is confronted by a mystery man (Robert Blake), and the surreal really starts to kick in for the film. Next thing we know, Fred is convicted of murdering Renee, and he’s on Death Row, when something happens, and he “becomes” Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty), a 20-something auto mechanic who finds himself involved with a mob boss (Mr. Eddy, played by Robert Loggia) and his bombshell girlfriend, Alice (Arquette again).

In retrospect, it’s easy to see “Lost Highway” as a test run for what he would do with “Mulholland Drive,” but the film has a friskier sense of dark humor, and a deeper connection to film noir than “Mulholland Drive” does that is where it finds its footing. Even if you don’t necessarily get to the point of figuring out how Fred “turns into” Pete, and all the mechanics of Lynch’s storytelling, it’s a delicious piece of noir with some of Hitchcock’s “innocent man wrongly accused” plot structure thrown in, and you just learn to run with it. My biggest issue with it is that the screenplay by Lynch and Barry Gifford feels very surface-level engaging compared to the depths of theme and character he would explore in what came after. This is a noir exercise, Lynch trying out his sea legs, and I find myself enjoying it on that level. The performances are fine- with Loggia and especially Arquette giving the best performances in the film, and one scene with Richard Pryor being a welcome surprise- but it’s difficult to feel much for the characters beyond a narrative interest. This is about style and Lynch trying things out; he had deeper ideas to dig into later down the road.

It’s been a long road for me to get to the point where I “like” “Lost Highway” after I hated it in 1997, before my appreciation of Lynch took hold, but one think about “Lost Highway” has always been a love of mine, and that is the soundtrack produced by Trent Reznor, and including one of Nine Inch Nail’s best songs, a great David Bowie gem, and some hard metal from Marilyn Manson and Rammstein in addition to a jazzy score by Angelo Badalamenti that might be the best score he ever composed by Lynch. The convergence of those two sounds play beautifully with Lynch’s bizarre narrative, and has always a soundtrack that, when you listen to it again, makes you think of the lush, seductive images, and wild ways the narrative contorts into as Lynch finds himself looking for answers to where his cinematic vision will go next. I’m glad to go with him now.