On the Waterfront

“On the Waterfront” serves two purposes. The first is to tell a compelling, character-driven story about a former boxer-turned-longshoreman who becomes a snitch about criminal activity in his union. The second, and more personal purpose, was to act as a reflection and justification of it’s director, Elia Kazan, and his decision to name names to the House Un-American Activities Committee in the early ’50s, who was looking to expose communists during the early days of the Cold War. Despite this film’s rapturous reception, including the Best Picture Oscar, Kazan was never treated the same again, and indeed, when he received an Honorary Oscar decades later, half the audience in the theatre booed and held back applause. But Kazan never apologized for what he did, and he was upfront about why he made this movie, which is still alive and vibrant 60 years later.

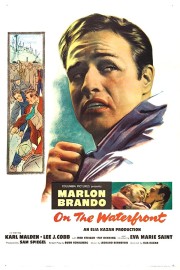

The film was the second one Kazan had made with Marlon Brando after their simmering “A Streetcar Named Desire,” and together, they transformed American movie acting. The image of Brando in his later years, before dying in 2004, is tough to get past, but one look at “Streetcar” and “Waterfront,” and you see how influential Brando was before his oversized ego, and overweight physique, took over in our perception of the actor. There’s something natural and lived in about Brando in these films with Kazan, and it’s a remarkable thing to watch. I’ve always been partial to “Streetcar” myself, but watching “Waterfront” again, and especially in his scenes with Eva Marie Saint, and you find yourself drawn in by the subtlety and character Brando brings to the role, which won him the first of two Oscars.

Written by Budd Schulberg, and based on a true story, “On the Waterfront” tells the story of Terry Malloy (Brando), a prizefighter who now works odd jobs on the shores of New Jersey. He also is a low man in the pecking order for criminals who run a corrupt union, which we see early on when he sends a message that gets a union man, Joey Doyle, killed when the bosses find out he was talking to the cops. That murder is what drives the plot of “Waterfront,” as Joey’s sister, Edie (Saint), his father (John F. Hamilton), and a local priest (Father Barry, played by Karl Malden), try to get to the bottom it, and try to convince someone, anyone working for the union to do what’s right, and tell the truth. Through the course of the film, Terry and Edie strike up a bond, which lowers Terry’s guard, and gets him thinking about doing what no one else would. As Terry says at one point, “Conscience. That stuff can drive you nuts.”

Kazan didn’t make “On the Waterfront” into an easy morality tale, but a complex look at choices. Yes, some of those choices are very black and white, but the world Terry and Edie live in is full of grey area. Terry owes a lot to a lot of people who have done questionable things, even his brother Charley (Rod Steiger), who is tasked with either talking some sense into Terry, or taking care of things himself at the beset of mob boss Johnny Friendly (Lee J. Cobb). However, talking to Edie changes something in him– he sees the chance for a different life, and a better life. You would think being honest about something like his role in the death of Edie’s brother would be easy for him, but it’s not, and we understand, through Brando’s performance, why it’s not an easy decision. Here’s a man who has had it easy for a long time. He’s never had tough choices to make, and it’s made for a good life. Now, life is getting difficult. He’s feeling pressure from all directions, most of all from himself. He wouldn’t take some of the risks he takes if he wasn’t wanting to change things. When Charley winds up dead later, Johnny Friendly intends it to be a warning, but for Terry, it’s the straw that breaks the camel’s back. He’s ready to take the chance he’s been struggling with, even if he isn’t ready for all the consequences of his choice. In the long run, though, it won’t matter to him, because as he says late in the film, “I’m standing over here now. I was rattin’ on myself all those years. I didn’t even know it.” He knows where he stands, probably for the first time in his life. And there will be rough times, but if he can make it through, he’ll no doubt be happier than he has been ever.

In real life, the snitch died, but Terry wins in the end. Kazan did, as well, as it’s impossible to deny the power of his film. This story could have easily been a manipulative Hollywood story of good vs. evil, but Kazan and Brando turn it into something that lives and breathes with purpose, and is buoyed by a score from the legendary Leonard Bernstein that captures the spirit of the film effortlessly. I’d say that it’s rare to see a Hollywood film so vibrant and honest nowadays, but the truth is, it was kind of rare back in the ’50s then, although thanks to people like Kazan and Brando, they were a little more frequent than they are now.