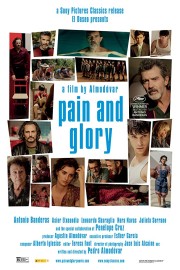

Pain and Glory

I cannot remember the last time I watched Antonio Banderas be so alive and passionate on film as he is in Pedro Almodovar’s “Pain and Glory.” Granted, it’s been a while, I think, since I’ve seen him in a film (I missed his last Almodovar collaboration, “The Skin I Live In”), but this is a different sort of role for him. I’m so accustomed to his work in action via his performances for Robert Rodriguez, it’s been forever since a soulful, charming performance has been seen by him from the actor. In a year of great acting nominees, this might be one of my favorite nominated performances.

I’ve been following Almodovar’s career in fits and spurts since I watched “Live Flesh” in the late ’90s, but “Pain and Glory,” which feels like an autobiographical meditation from the “Talk to Her” and “Volver” director, makes me want to rectify those blind spots in his career as soon as I can. In a way, this movie feels like he’s doing his riff on Fellini’s “8 1/2,” which was about a filmmaker stuck with his psychological baggage, and lacking inspiration creatively, but there’s something a bit more thoughtful and moving in what he’s doing compared to Fellini’s film. This might be my favorite film of his.

We begin with several women washing clothes down by a riverside. One of them (played by Penelope Cruz) has a young son, Salvador (Asier Flores), and we will follow them as they journey to live in the catacombs of a small town with Salvador’s (largely) absent father, and then as they make a trek alone, as well as some glimpses of Salvador as a kid in a Catholic school, which fuels his creative talents, but stunts his education. We also see Salvador as an old man, played by Banderas, whom was a well-regarded filmmaker, but hasn’t made a film in years. He has health issues with pain in his back, headaches, and risks choking when he has something to eat, even when it is pureed. One day, his assistant, Zumela (Cecilia Roth), tells him that a local Cinemateque is showing a restored version of an earlier film of his, “Sabor,” and would like him to present it with the film’s star, Alberto Crespo (Asier Etxeandia), at a future showing. The catch is, he and Crespo, who went on to become a popular star, have not spoken in 32 years, after Salvador was upset that the actor did not perform the character as he hoped. A recent viewing of the film has softened him on the movie, though, and Salvador tries to reconnect with Alberto in hopes he will agree to present the film with him. That opportunity for reconciliation will be the catalyst for a sea change in Salvador’s perspective at this moment in his life, which is two years removed from back surgery, and four years removed from the death of his mother, neither of which he has fully recovered from.

Almodovar is a master of shifting moods, going between melodrama and drama, dark comedy and warm humanity, but the thing I love about “Pain and Glory” is how it’s all human nature, all about characters interacting, taking chances and opening up in ways they did not expect when the opportunity first arose, and seeing where it takes them when they do. This is a film that spoke unexpectedly to me right now, as I find myself in the middle of a particularly hard moment of my life, and feeling too burnt out to create. Movies like “Pain and Glory,” which has all of Almodovar’s meticulous beauty and filmmaking passion, are the sort of experience that can rejuvenate you, and that is where Banderas’s performance comes in. I forgot how naturally charming he is, but he also has a pain he needs to bring out of the character even when he’s interacting with someone who brings out the light in him like Zumela or Federico (Leonardo Sbaraglia), a school-age friend he reunites with unexpectedly. I feel as ready to move on to the next phase as Salvador does by the time this movie ends. I am renewed, and ready to drive through personal pain towards personal glory, as well.