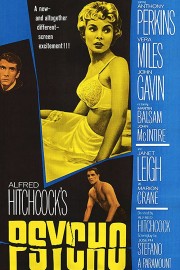

Psycho

This is a movie I don’t have to watch first before reviewing, but let’s face it, even if you’ve seen a movie a dozen times, chances are, you might see something in it that you didn’t before that will help in your review. I don’t know if that explicitly happened in this latest viewing of Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho,” but honestly, I’m glad I watched it, because I have some thoughts that popped into my head during it.

Before I dig too deep into the film, I wanted to comment on the source of inspiration for the film. It’s accidental that, this October, I am reviewing this and Tobe Hooper’s “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” back-to-back; I realized late that I was missing a week in October for a “Movie a Week” film, and I chose “Massacre” out of respect for Hooper, who passed away earlier this year. That being said, it’s interesting to basically watch how two different filmmakers were inspired by the same story in their tellings. As horror fans know, both “Texas” and Robert Bloch’s novel for Psycho were inspired by the case of Ed Gein, a serial killer in Texas. Now, Hooper’s film hues closer to the actual story than Bloch’s book, and Hitch’s film, but what’s interesting in having both films not only exist, but be classics, is that it means the same story is basically ground zero for the slasher genre of horror that “Halloween” and “Friday the 13th” helped solidify, and make profitable in the 1980s. (Gein was also the inspiration for Buffalo Bill in “Silence of the Lambs,” but that’s another story.) Hitch could not have imagined when he was making “Psycho” in 1960 that he would help redefine a genre for a generation, but “Halloween” and “Friday the 13th” and “Texas Chain Saw Massacre” next to “Psycho,” and structurally, similarities will become clear between the two. I don’t think it was an accident that Universal, which then owned the film, produced sequels to Hitch’s masterwork as the ’80s moved forward- Norman Bates is one of the most compelling villains in movie history- who wasn’t going to see more of his story? (Confession- I haven’t seen any of the sequels. I do want to, however.)

This was Hitchcock’s first black-and-white film in a decade, made on the cheap, and that he regarded it, in terms of budget and style, as not equivalent to “Vertigo” or “North By Northwest” or “Rear Window” doesn’t mean he didn’t put his personal stamp on it. Made with crew from the “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” TV show, “Psycho” feels like something more scandalous and unsettling than his other “great” thrillers, and that is by design. Hitchcock wanted to do something with minimal Hollywood artifice and with a style closer to the film noir that had taken over the crime genre over the previous decade-plus. That “Psycho” would then bridge that into the horror genre, with moments that are genuinely unnerving, makes Hitch’s accomplishment all the more stellar. On the one hand, it is every bit a piece with Hitch’s body of work, while on the other hand, it helps film noir and its anti-heroes work its way into horror in a way that wouldn’t be felt until two decades later. This is a startling piece of work from the filmmaker, and it’s unlike anything else he ever did at the peak of his powers.

One thing that I noticed while I watched the film this time was Norman Bates’s behavior after Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) goes to her room after they eat in the parlor. Not where he removes the picture to reveal the peep hole, but after he takes the food back up to his house. He paces and sits in the kitchen. He’s not hurried. He’s not stressed. He’s thinking. Part of the genius of Anthony Perkins’s performance is that there is no indication at all that Norman is the killer until we see him in that wig and dress at the end. Yes, we know something is not quite right by how calmly he cleans up Room #1 after Marion’s death, and we figure he is the killer after the sheriff tells Sam (John Gavin) and Lila (Vera Miles) that Norman’s mother is dead when they visit him after not hearing from Martin Balsam’s Arbogast, but there is no tangible indication on Perkins’s part in his performance of the reality of Norman Bates. It’s only in the narrative hints in the sheriff’s dialogue, and in Hitch’s staging of moments with Norman and his mother, that we get an idea that something deeply troubling is wrong. Even with the dialogue he has with Marion about his mother, you can chalk that up to Norman being either emotionally abused by his mother, or overprotective of her. The script by Joseph Stefano is a wicked piece of writing that cares deeply about how Norman is portrayed, because, once Marion is killed, he is our protagonist throughout the rest of the film. Our sympathies lie with him, even when we see his true nature, and one of the most overbearing psychiatrists in film history lays it all out for us in a scene that Roger Ebert hated. I disagree with him, to a point, but I certainly understand his point when the psychobabble rationales of Norman’s actions make the eyes glaze over. Still, if that’s the only false move made by one of the greatest filmmakers of all-time in one of his greatest films, it’s hard to quibble much.

Among Hitchcock’s work, I still think “Vertigo” and “Rebecca” are shades ahead of it, but “Psycho” is, handily, the master’s most accessible film, with “North By Northwest” not far behind. As many chances as he took with this film (the narrative switch from Marion to Norman as the protagonist after the shower scene, the black-and-white photography, Bernard Herrmann’s shrieking string score), he also knew exactly how to push his audience’s buttons, and few have twisted the knife of suspense and horror as Hitchcock down here. This isn’t “high art” like “Vertigo,” but it’s a work of art like few others have managed before. You won’t be able to get it out of your head.