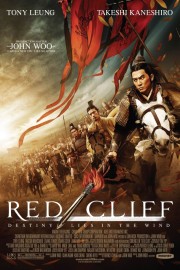

Red Cliff (U.S. Version)

Now I want to watch the Chinese release.

I could go on with hyperbole. How this is the Chinese “Gone With the Wind.” Or John Woo’s “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.” Or I could just dive into this epic for its’ own sake.

A thing for American audiences to understand- this isn’t the whole thing. Woo’s original vision of the Battle of Red Cliff actually spanned two films in its’ native China (which outgrossed “Titanic,” no less), five hours of film, and cost roughly $80 million to make (the largest film ever made in China). Fret not, though- the 2 1/2 hour cut currently playing in theatres throughout the rest of the world was part of Woo’s plan all along. If you leave that version wanting to see the whole thing (like I did), don’t bother with bootlegs- Magnolia Pictures has set a DVD release of both versions for March 30.

Although like me, you may not want to wait that long. Woo’s “Red Cliff” is one of the finest historical epics I’ve seen, comparable to Kurosawa’s “Ran,” Tarkovsky’s “Andrei Rublev,” Gibson’s “Braveheart,” and yes, “Lawrence of Arabia” in scope and excellence. Even if you don’t know about the famous Battle for Red Cliff- which brought an end to the Han Dynasty in 208 A.D.- you’ll want to by the time the film finishes.

Woo has a lot of characters to set up, a lot of conflicts to resolve, and a lot of story to tell. And he’s up to the task with extraordinary confidence and skill. His storytelling hasn’t been this sure (and his approach this loose) since his last Hong Kong film, the classic “Hard-Boiled,” in 1992 (although his American-made masterpiece, 1997’s “Face/Off,” the purest distillation of what made him a master of action). He uses voiceover and character identification onscreen (both in English) to help expedite the process. It’s not always easy to follow (although Woo, save for one easily noticeable edit from night to day during the long end fight, condenses the story brilliantly), but you never lose interest.

As the film begins, Emperor Han (Wang Ning) is forced into military battle by his Prime Minister Cao Cao (Zhang Fengyi), a war-mongering general who claims to be fighting for the preservation of the empire. The targets are supposed “rebels” Liu Bei (You Yong) and the young Sun Quan (Chang Chen) of the Southlands. The real purpose is the wife of Sun Quan’s mentor, Viceroy Zhou Yu (“Hard-Boiled’s” Tony Leung), whom Cao Cao wishes to take as his own.

After one “defeat” at the hands of Cao Cao, Liu Bei sends his brilliant strategist Zhuge Liang (Takeshi Kaneshiro) to Sun Quan to convince him to fight with Liu Bei. They succeed, and with Zhou Yu leading the combined forces, bracing for Cao Cao’s massive army, which is coming by land and by sea, at their outpost at Red Cliff.

In the films of John Woo’s I’ve tended to love most, music plays an interesting role in the story (or the film’s overall effect). In “The Killer,” Chow Yun-Fat’s hitman blinds a bar singer, whose songs illuminate the loneliness and love to come. In “Hard-Boiled,” not only does Yun-Fat’s character play clarinet, but Leung’s undercover cop uses song lyrics and melodies to communicate with headquarters. In “Face/Off,” Woo uses Olivia Newton-John’s version of “Over the Rainbow” to maximize the emotions in a shootout. And in his underrated WWII film “Windtalkers,” a Navajo codebreaker bonds with his American protector (Christian Slater) over his native music.

“Red Cliff” offers up another moment like this. Zhuge Liang has arrived at Red Cliff to convince Viceroy Zhou Yu to fight. Instead of talking politics and strategy- of which they will both prove their brilliance in- they instead play a duet on a zither-type instrument. It’s not that they both are talented at this instrument but that they perform so well together after mere hours of knowing one another. The music makes it a beautiful sequence- haunting and original in a war movie- but the subtext makes it a key sequence for both characters and audience.

These are the type of moments Woo inserts so masterfully in his films (with his best ones practically hinging on them at times), and there are more to mention (and probably additional ones that didn’t make the U.S. cut). But you want to know about the action, right? Fret not- Woo is at the peak of his artistic powers, staging epic battle scenes with the ferocity and power of his best action sequences (the church shootout in “The Killer,” the hospital in “Hard-Boiled,” the loft in “Face/Off”), but on the scope of “Lord of the Rings” and “Ran.” Yes, slow-motion is used for effect, but not at the self-parodying rate of “M:i-2.” Yes, a dove is even flown above a massive naval army, but there’s a story purpose for it. The familiar Woo elements are here, but in service of the story and themes Woo wishes to hit on. Friendship. Loyalty. Betrayal. Revenge. Woo has hit on them before, but here we see them in a much larger context, and at times, in more profound ways than he’s shown them before.

The film is technically superb, with Oscar-caliber costume design, art direction, music (by Tarô Iwashiro), and cinematography (a shared credit for Lu Yue and Zhang Li) that takes your breath away on the big screen. And save for one awkward, mid-battle cut near the end (the most glaring one in this superb undertaking), Woo and editors Robert A. Ferretti, Angie Lam and Hongyu Yang keep the film moving at a breakneck pace that doesn’t short character development or storytelling.

But like any undertaking on this level, it all comes down to story and performances, and on both counts, Woo (who co-wrote the script, adapting a portion of the famous Chinese work “Romance of the Three Kingdoms” with Khan Chan, Cheng Kuo and Heyu Sheng) and his actors shine. Leung and Kaneshiro share the spotlight most predominantly, and don’t disappoint in showing the bond that develops between these two. The other actors don’t miss a beat either, but these two are the ones you’ll remember. Their bond when the situation is dire, their resolve when the winds of change go their way is- like most Woo films- the bond you’ll remember above all. This type of story, which illuminates the bonds between men who otherwise couldn’t be more different, is what energizes his films. In “Red Cliff,” it turns what could’ve been a routine epic into another classic for a filmmaker who needed to find his artistic footing after a decade of largely disappointing Hollywood products.

I can’t wait to see what he has in store next.