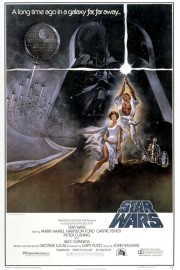

Star Wars: A New Hope

“Star Wars” and I are both going to be 34 this year; on the one hand, that’s a sobering thought, but on the other hand, it has meant that that galaxy far, far away has always been a significant benchmark in my life. Released unto the world in 1977 (on this day, in fact), George Lucas’s space opera has occupied a planet-sized place in popular culture ever since; not even the diminished creative returns of a prequel trilogy and a more kid-friendly focus over the years can sully its position as THE iconic fantasy adventure franchise of the past 50 years, although yes, some have come close to supplanting it (see “Lord of the Rings” and “Harry Potter”).

Intellectually speaking, it’s quite obvious that “The Empire Strikes Back,” the second part of Lucas’s original trilogy, is the creative high point of both that original trilogy and the franchise as a whole, but I remain loyal to “Episode IV- A New Hope” (as it would later be subtitled) as both the artistic benchmark and emotional anchor of the franchise. Yes, Lucas and the wizards at Industrial Light & Magic continued to push the boundaries of visual effects with each film, John Williams composed his greatest and most imaginative scores as the series progressed (cough”The Empire Strikes Back”cough), and the most interesting story developments came the more we got to know the characters (Darth Vader is WHO’S father? Leia is WHO’S sister?), but this original adventure captures the same excitement and sense of fun other iconic entertainments of decades past delivered (think “The Adventures of Robin Hood,” “Jason and the Argonauts,” and the original “Planet of the Apes”) and many Hollywood blockbusters that came after would forget.

“A Long Time Ago, In a Galaxy Far, Far Away…”

Have ten words seen on screen become so famous in film history? Over time, the words seemed to lose some meaning, when foolish alien antics and trade disputes would take over the franchise in both the prequel trilogy as well as the kid-friendly “Clone Wars” television show, but seeing them in “A New Hope” and the two films that followed it (“The Empire Strikes Back” and “Return of the Jedi”), even now, means something. It means entering a world that was beyond our imagination. It means watching a story unfold that is both familiar in its archetypes, but unfamiliar in the ideas and sights it shows us. And it means giving ourselves over to a storyteller who is both reverent to the myths of the past, but is also fearless in showing us something new onscreen. These are not places of our own world, nor are they a reflection of the world we live in.

Or are they? It’s been said that many times that movies are a reflection of the time they were made. I’m not sure if that’s entirely true (can one imagine “Rio,” or “Your Highness” as a reflection of the modern world?), but I think there’s some truth to that when you consider the “Star Wars” franchise, both the original films or the prequel trilogy. This shouldn’t be surprising to fans of George Lucas: his 1971 feature debut “THX 1138” is a masterpiece of “hard” science fiction that reflects philosophical and political ideas of free will that were prevalent at the time, while his “American Graffiti” was an affectionate and autobiographical look at growing up in the ’50s, but was also a reflection of the freedom youth felt in the ’60s. In many ways, “Star Wars” is an autobiographical film for Lucas as well, as he and his filmmaking friends (Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Brian De Palma et al) were rebelling against the Hollywood system of the time as the old studio system was being dissolved and replaced by a corporate empire. I think you can see how that real-life unrest, which Lucas was on the front lines for, plays into the “Star Wars” trilogy.

If I’m not spending a lot of time discussing the story of “A New Hope,” it’s because even for people who haven’t seen the films, the story, the characters, and the mythology Lucas created are well known, which is as strong a validation of Lucas’s overall success with the franchise as anything I can think of. It’s sheik for people of my generation to dump on Lucas and “Star Wars” now, and it’s very true that some of Lucas’s creative and business decisions, from the frequent tinkering with the original trilogy to the largely inferior prequels to Lucas’s lack of perspective when it comes to the release of the original trilogy for home viewing, deserve such ridicule. But as other writers (namely Drew McWeeney in his superb review of the documentary, “The People vs. George Lucas”) have pointed out, such bitching and moaning only illuminates how much of a place in modern culture “Star Wars” has maintained. If the prequels were merely bad (or you know, part of another franchise like “The Mummy,” for example), people would just forget them and get on with their lives. But with “Star Wars,” I get it– for many people (myself included), this is ground zero of our film love, and even if the people tinkering with our memories of the franchise are the creators of that universe, it’s easy to get overly protective. After all, I didn’t grow up watching Han Solo (Harrison Ford) jabber on with a mobile Jabba the Hutt before escaping Tattoine, or seeing goofy creature comic relief heading into Mos Eisley, or watching Greedo shoot first because Han shooting first isn’t how real heroes do it. (Have you SEEN Han in “A New Hope,” George? Not exactly Robin Hood or a Knight of the Round Table that one.) My strongest memories of “Star Wars” include: the mentoring about the Force of young Luke (Mark Hamill) by Obi-Wan Kenobi (Sir Alec Guinness), and the old warrior’s death at the hands of Darth Vader; the love-hate friendship of robot sidekicks C-3PO and R2-D2; the excitement of the dog fight as our heroes try to escape the Death Star; and the majestic sound of John Williams’s music after the Death Star is destroyed, and our heroes are rewarded for their bravery. None of these memories can be touched by Lucas because he can’t change the feelings and images I’ve carried with me as a result of this film.

All that being said, time has provided some perspective on “Star Wars.” While few blockbusters can claim as memorable of dialogue as “Star Wars,” even in the early days of his career it is easy to see that Lucas was less interested in directing actors and performances than he was in the technical tools he used to tell his story. The story has moments that lack some common sense: How is it Luke doesn’t appear to grieve for the Uncle and Aunt whom have raised him are killed, but when Ben Kenobi dies he almost looks like he’s ready to fall to his death in Beggars Canyon back home? And in the end, the film lacks much depth in its story; there’s not a lot of growth beyond plot necessities, and the old “good vs. evil” philosophy of the film is less interesting than wondering how they made the film technically. Still, the kid in me continues to love “Star Wars,” whether it’s the rough visuals of the version I grew up with or the misguided updates Lucas has made over the years in his quest to “perfect” his vision of the film. A note to George– you got it right the first time. Why else would we still be watching it 34 years later?

Some more about “Episode IV,” and in particular, the “binary sunset” scene, I wrote about for a class in 2014:

Because of the digital alterations and enhancements George Lucas has made to his original trilogy over the years, choosing a shot from the original “Star Wars” film, “Episode IV- A New Hope,” is a tricky proposition. However, regardless of whether you are watching the original theatrical version on VHS or the digitally enhanced moment on DVD or Blu-Ray, there is a shot about 25 minutes into “A New Hope” that speaks volumes about the story we are watching unfold.

The “binary sunset” scene in “Episode IV” establishes the story for the remainder of the movie, and even the trilogy as a whole. At the outset, “Star Wars” establishes itself as a space adventure filled with rousing excitement and visuals. After C-3PO and R2-D2 are captured by scavenger aliens known as Jawas, and sold to an old man and his nephew (Luke Skywalker), though, the action slows down for some exposition. A scene of Luke cleaning the droids, getting them ready to begin working on the man’s moisture farm, follows, and concludes with a hologram of Princess Leia asking for the help of Obi-Wan Kenobi. We then move to a dinner scene where Luke tells his uncle Owen and aunt Beru about the hologram, which leads into a discussion of Luke trying to get his uncle to let him go to flight academy a year earlier than they had previously agreed upon. His uncle doesn’t not relent, however, leading Luke to leave the table in frustration, and go outside.

When we cut to an exterior shot, we watch Luke walk onto a small hill during a long shot. The sun(s) on the planet are setting in the distance, with a building structure in the foreground on the left; some mechanical items on the right, at approximately the same distance as Luke appears; and another mechanical item (a moisture vaporator) off to the extreme right of the shot, farther away in the shot than Luke is. (See the picture just above.) We then cut to a medium close-up of Luke looking off into the distance at the sunset, which is followed by an extreme close-up of the suns before cutting back to the medium close-up of Luke, seen above. This shot (the medium close-up of Luke), coupled with the dialogue scene that preceded it with his uncle, establishes Luke as a character who is unhappy with his current life, and longs for something more, which is all the development we need to know that this is our main character for the rest of the film. More so than the dialogue, the shot of Luke watching the sunset, however, does more to tie our emotions during the remainder of the film (and eventually, the trilogy) to the journey Luke will take than any piece of dialogue could. Even if we haven’t necessarily had that type of moment in our own lives when we first watch the film, we understand what Luke is feeling, because he is established as an archetypal “young hero,” and when he gets his wish to leave his life behind not long after when he meets Obi-Wan, though it isn’t the way he wants to leave (his aunt and uncle are killed by Imperial Stormtroopers searching for C-3PO and R2-D2), we understand the resolve in his voice when he tells Obi-Wan he wants to become a Jedi. And if/when we do have that moment for ourselves, where we find ourselves at a great divide in our lives, it’s almost impossible for us not to think about this moment, and feel a kinship to Luke as what he needs to do (help his uncle for one more year) is in conflict with what he wants to do (be a pilot).

It’s extremely difficult to discuss a single shot without the context of what is around it to give it further meaning, but watching Luke look off at the sunset, dejected, facing a future he doesn’t want, longing for a future he isn’t ready for, even if he thinks he is, is a moment that lives on in us, regardless of whether we’ve seen the movie recently, or whether it’s been years since we watched it. (Yes, John Williams’s score aids in that immeasurably, but that’s a discussion for another time.) As an image, though, the “binary sunset” is an iconic moment in movie history, and an important one to the narrative of George Lucas’s film.