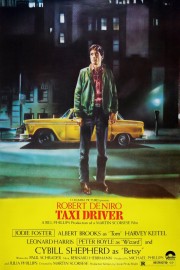

Taxi Driver

It’s been about 20 years since I first saw Martin Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver,” and it occurred to me that I had been remembering it as being more violent than it was. Such is the effect of Scorsese’s penchant for bloodshed for much of his career. But with the exception of one moment when Travis Bickle stops a robbery in progress at a convenience store, all the violence is relegated to the last 20 minutes of the movie, when Bickle, the titular taxi driver played so unforgettably by Robert DeNiro, goes on the warpath to get Iris, a 12-year-old prostitute played by Jodie Foster, out of the work she is in, whether she wants to be rescued from it or not. That last part is key to understanding Travis’s character- he acts based on his own understanding of the world, without much regard for what the person his actions wants. He sees himself as a savior, but actually, his behavior is closer to that of a sociopath, whose only regard is for themselves.

Rewatching the film after so long, I couldn’t help but look at Bickle as someone who suffers from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder from his time in Vietnam. We see that he keeps a journal of his thoughts and what happens from day to day. We know from his interview for his cab job that he was in the Marines, although I wonder whether he was honest when he told his prospective boss that he was honorably discharged. What we learn about Travis, and his tendencies to see people who don’t appear to have his interests at heart as adversaries may shine some light on his background. We meet Travis at a set point in time, and while Scorsese and his writer, Paul Schrader (whose script was inspired by John Ford’s “The Searchers”), fills in some blanks along the way, I wonder whether it’s much of a stretch to consider Bickle an “unreliable narrator.” While it’s obvious he’s a man who lives by a set of principles, he also doesn’t think twice about the idea of assassinating a presidential candidate, or when a fare (played by Scorsese), who has him drive to where his wife is having an affair, casually talks about killing her lover. A man who has trouble sleeping at night (which is why he does night runs), he sees himself as someone who can wash away the filth he sees in the city.

While I admired the film when I first saw it in 1996-97, it didn’t have the impact on me as it did others. I was still relatively green as a critic, and was just getting into cinema as a popular pastime. After 20 years of Scorsese films, and thousands of films seen, however, I understand its greatness a bit better, and it comes from the spiritual emptiness Scorsese and Schrader instill in the character of Travis Bickle. Spirituality is something tangible and powerful within Marty’s characters, making the lack of it in someone like Travis, or the paramedic in Scorsese’s “Bringing Out the Dead” (which I reviewed last year for this series), even more pronounced. Travis laments the lack of morality he sees on the streets he is traveling at night, and yet, he makes no bones about going to a porn film himself. He has no reservations with people who hire prostitutes riding in his cab, yet when he sees one (Iris) pulled out of his, seemingly against her will, he decides he must act in a way he sees fit, even though her words later give the impression she is satisfied by the life she lives. Roger Ebert, when he reviewed the film in 1996, likened Bickle to a Boy Scout helping an old woman across the street, whether she wants to go or not. That’s a good description of the character. In thinking about it further, though, it’s not that Travis lacks spirituality, but rather, his priorities are set more by what he needs, rather than what others need. We’ve seen plenty of people over the years who have acted similarly in the name of their own “spirituality.”

It’s easy to simply list the things that are great about a film, especially a Scorsese film, but it’s tricky to find a distinctive voice when reviewing a film hundreds have reviewed before, and one so well known as “Taxi Driver.” Ebert’s “Great Movies” review covers a lot of bases about what makes Marty’s film great, but there is one I’d like to discuss for a bit, and that is the score. Scorsese is one of the great music directors in cinema, which is to say, he uses music in a way that turns a good scene into a great one, and a great scene into a classic scene. Many times, this is because of an existing song or piece of music he uses as underscore, but he also allows for imaginative scores to be written for his films. (Think Peter Gabriel for “Last Temptation of Christ,” or Philip Glass for “Kundun.”) “Taxi Driver” has a score by Hitchcock’s great composer, Bernard Herrmann, and it was the last score he wrote before passing away. Infused by jazz, but also reminding astute listeners of his great scores for “Citizen Kane” and “Vertigo,” Herrmann’s work feels very much as a reflection of Travis Bickle himself, filled with pain and anxiety, just out-of-step with society as a whole, but beautiful and sad, as well. It’s hard to imagine a more perfect reflection of the character, or a more poignant accompaniment to a film that has a brutal reputation, but is, in fact, a powerful and poetic expression of how life seen through certain prisms can be messy and devoid of meaning except that which we give it.