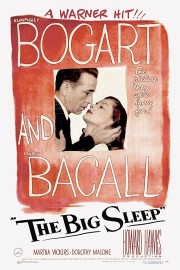

The Big Sleep

**I wrote about Dorothy Malone’s scene in “The Big Sleep” for In Their Own League. You can read that here.

Howard Hawks’s “The Big Sleep” tells one of the most complicated stories in all of film noir. In doing so it inspired one of the shaggiest dogs of modern film, the Coen Brothers’s “The Big Lebowski.” Neither of them bring their story to a satisfying conclusion in the conventional sense, but you won’t find a fan of either film that doesn’t enjoy the film nonetheless.

But “The Big Lebowski’s” time will come; this is about Hawks’s film, and the people who populate it. Humphrey Bogart plays Phillip Marlowe, the iconic private dick of Raymond Chandler’s novels who is hired by General Sternwood (Charles Waldron) to uncover the truth behind his being blackmailed by a supposed rare books dealer with regards to his younger daughter Carmen (Martha Vickers). Already you can see the complications begin, and they’ll continue throughout the film as Sternwood’s older daughter Vivian Rutledge (Lauren Bacall) gets caught up in the case as well, which leads to dead bodies and uncertainty as to who did the killing. The latter led to one of the great legendary anecdotes in film history, when Bogart asked Hawks who killed Owen Taylor. Hawks then called up Chandler, who said he didn’t know either. Of course, by the time Taylor ends up dead you won’t care if they solve it, so intoxicating is the film to watch.

Hawks was a great Hollywood craftsman; unlike filmmakers like Orson Welles and John Huston who would follow their own rules, Hawks (“His Girl Friday,” “Rio Bravo,” “Red River”) worked within the system and built a career based on sheer storytelling craft. His rule of what makes a good movie: “Three great scenes, no bad ones.” Few films have had more great scenes than “The Big Sleep.” The script by William Faulkner, Jules Furthman and Leigh Brackett is a model of smart and funny screenwriting; scenes follow an unusual way of building up to unexpected conclusions, even for those who have seen it before like I have. We’re drawn in my the characters and the story, but what we remember is the way the characters interact. Like when Marlowe first visits the Sternwoods, and Carmen flirts shamelessly with him; Marlowe then tells the general, “She tried to sit in my lap while I was standing up.” Or when the sick general tells Marlowe about having people do his drinking and smoking for him. The way Marlowe works during interrogations with “interested parties,” getting them to reveal more than they would like to.

And then there are the scenes that boil over with sexual tension and snappy dialogue. The first is a personal favorite, when Marlowe is staking out a man named Geiger (who runs a rare books store); it starts to rain, and he goes into a book store across the street to stay dry. That doesn’t last very long when he and the book clerk in the store (Dorothy Malone) get to talking; she finds him interesting, he prefers her without glasses and with her hair down. I prefer her the other way, but I’m not Marlowe. Scenes like that make me wish I was, though. The other scene was added after test screenings showed Warner Bros. that the chemistry between Bogart (their biggest star) and Bacall (whom he just started a relationship with) wasn’t quite what it was in their previous film together (Hawks’s “To Have and Have Not”). In it, Marlowe and Mrs. Rutledge are having dinner, and they get to talking about gambling. Apparently they’re both into horse racing, although listening closely to the dialogue gives you the distinct impression they’re talking about something else.

It’s dialogue like this that makes movies like “The Big Sleep” more than just mere entertainment; they’re a great reminder of the pleasures of what smart writing, direction and performance can bring to a movie. We miss that watching most of the films nowadays– stars were genuinely stars, directors were allowed to hone their craft, and a script was more valuable than special effects in getting studios to sign off on a movie. In “The Big Sleep,” we get to see two of the biggest stars of Old Hollywood and one of the best directors of any era work from one of the great scripts to tell a story that doesn’t go the way we expect, and doesn’t end the way most audiences would prefer, unless all you care about is seeing Bogart and Bacall ride off in the sunset together. Sounds good to me.