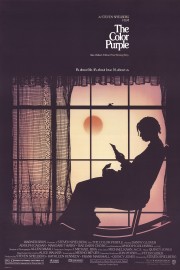

The Color Purple

I wasn’t quite sure what to expect from watching Steven Spielberg’s “The Color Purple” for the first time in about two decades. The film was his first really serious film, and it did have an effect on me when I first watched it, but would it hold up compared to the likes of “Schindler’s List,” “Saving Private Ryan” and “Lincoln?” Much has been written about how Spielberg sanitized a lot of the darker, and more controversial (at the time), aspects of Alice Walker’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book for mass consumption- would it still seem worthy of the acclaim it nonetheless received now, or would it feel too sentimental from the filmmaker?

I have not read Alice Walker’s novel, but given how painful life is for Celie, the main character played, as an adult, by Whoopi Goldberg, in Spielberg’s film, I’m not sure I want to know how much worse things are for her in the book. We begin by watching young Celie play with her sister, Nettie, in a crop field. We notice that Celie, who cannot be more than 13-14, is pregnant, and then, we see her giving birth. When her daughter comes out of her, the light in her face turns to misery when her father comes and takes the child out of her hands, telling Celie that she best not tell anyone about this besides God. We understand what happened clearly- this man has raped Celie, and he is expelling the evidence from his house, and this isn’t the first time this has happened. Not long after, Celie and Nettie’s mother dies, leaving them alone with this man who they see as their father. One day, a local farmer, whom Celie will know as Mister (Danny Glover), comes by, asking her Nettie to be his wife. She is still too young, so the father offers Celie. They are married, and Mister is no better than the father, humiliating Celie by using her for sex and beating and berating her if she even slightly gets out of line. All the while, we hear Celie’s voice on the soundtrack, and empathize with her plight, one which will continue for decades.

Spielberg’s film is shot like a postcard by his “E.T.” cinematographer, Allen Daviau, but it’s not a pretty film to watch. The North Carolina locations where Spielberg shot the Georgia-set film may look beautiful, but that is in stark contrast to the story that unfolds within these images. Celie has times of happiness of Nettie, who has run away from their father, and is allowed by Mister to stay with them, for a time. Nettie teaches Celie and the two rekindle their sisterly bond, but when Nettie wards off Mister’s sexual advances, he kicks her out, and Celie will not hear from her again. Nettie tries to write her, but Mister controls the mailbox, and makes sure that Celie and Nettie have no contact. Women are not treated well in the film, and strong women are treated as threats. This is especially true of Sofia, the woman played by Oprah Winfrey in her first movie role. Sofia is a woman Mister’s oldest son, Harpo (Willard E. Pugh), comes home with, and she is not going to take any disrespect from Harpo. When he tries to get her to submit the way his father has done with Celie, Sofia isn’t afraid to hit right back, and even though she loves Harpo, eventually, she has to leave him with their kids because she isn’t going to be abused by him. She is one of two women who will serve as role models for Celie as she gains her self-respect.

The second woman is Shug Avery (Margaret Avery), a jazz singer, and Mister’s true love; he has pictures of her up in their bedroom, meaning Celie can see them when they have sex. She feels nothing during the act, and just figures he is thinking of her when the do it. Her first impression of Shug, who drunkenly tells her, “You sho is ugly!,” when Mister is bringing her in to the house, is not a good one. Mister tries to cook for her, but his meals end up thrown against the wall in disgust. When Celie makes her food, however, she eats it, and from there, the two form a bond. More so than Sofia, who will get into legal trouble when she tells the white mayor’s wife to go to Hell when she, patronizingly, asks Sofia to look after her kids, Shug becomes a surrogate sister to Celie, and, in one of the most tender and moving moments of the film, shows her what a meaningful, loving kiss is. (In the book, they become lovers, but it’s not surprising Spielberg was afraid to show that part of the story in 1985, although he does regret not having the courage to do so now.) More than that, Shug is responsible for the greatest wealth of strength that Celie gains in the film when she discovers what Mister has hidden from Celie all this time- that not only in Nettie alive, but she also has helped raise Celie’s long-lost children while on a missionary trip to Africa with the adoptive parents. This gives Celie something to live for, and something to long for, and Goldberg’s performance (her first feature film, and still her finest moment onscreen) is nothing short of unforgettable as we see Celie’s character change, and learn to stand up to Mister for the first time in her life. It is the kind of triumphant moment Spielberg has excelled at over the years, and why he was so right to direct the film. The dinner scene where Celie truly stands up for herself against not just Mister but his father (Adolph Caesar) is one of the most emotional moments in Spielberg’s career, matched later when Nettie and Celie’s children, and their families, return from Africa at the end of the film.

“The Color Purple” is not a flawless movie, by any stretch, but it is a powerful one. I don’t have as much of a problem with the scene of Sofia’s reunion, after years away, with here children as, say, Roger Ebert did, who said in his 2004 review that the humor of the mayor’s wife’s inability to drive, forcing an aborted visit, detracts from the emotion of that scene, but I would agree. In essence, it’s the heart of the movie, as a black woman is reduced to being humiliated and a servant to someone who wears their privilege on their sleeves, and will do whatever they can to put that woman, in this case, Sofia, in their place, as they see it. Now, Mister (played by Glover in a great, wicked role) is not as privileged as the white wife of a mayor (certainly not in the early 1900s, when the film is set), but he uses humiliation to control Celie throughout much of the movie, including inviting his mistress (Shug) to stay with them. That both of these women find the strength to get out of their toxic situations, and that Shug is a catalyst for that for Celie, at least, is one of the most satisfying parts of the entire film, and Goldberg, Winfrey and Avery play it like it means something, which it most certainly does. Whether the film is as hard-hitting as it could have been with Spielberg (more importantly, pre-“Schindler’s List” Spielberg) at the helm is irrelevant, but his film, with a lovely, emotional score by Quincy Jones (who brought the film to Spielberg), is one you won’t find it easy to forget. That matters more than anything.